Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

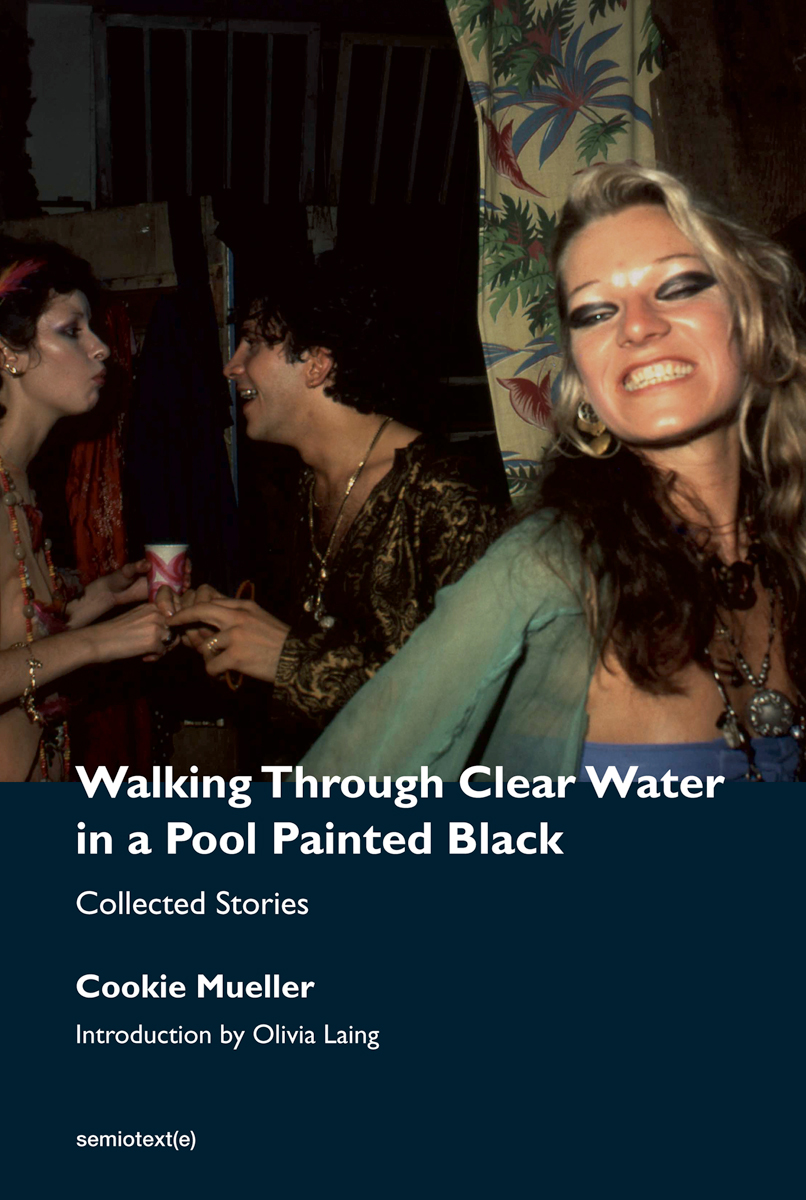

The pinkest flamingo: a new and expanded reissue of the writings of

John Waters–actress Cookie Mueller.

Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black: Collected Stories, by Cookie Mueller, Semiotext(e), 429 pages

• • •

The only way I can make it safely through a John Waters movie is to follow Cookie Mueller. Amidst all the coprophagy and épater-ing, there’s Cookie, eyes widened by mascara and heart opened by choice. In Edgewise, an oral history of Mueller, Waters describes her as “Janis Joplin-meets-redneck-hippie with a little bit of glamour drag thrown in,” which is only half the story. She became “sort-of-famous” (her phrase) thanks to Waters movies like Multiple Maniacs (1970) and used that spark to set off a writing career that burned through small magazines and alt weeklies. In 1971, in the middle of a cohort that had no time for respectability, she had a child, Max. She never abandoned her friends or her son—a dialectic a lesser artist would have obscured by turning it into a problem—until her death at forty in 1989 from AIDS-related pneumonia. Proto-punk, sure, because drugs and brevity and peril. But filmmaker Joseph Cacace has a better summary of Mueller: “She looked like a hard-ass, but she wasn’t.”

I love Mueller the actress, but I return to Mueller the writer. Her writing makes me feel the way many of her contemporaries did about her: hypnotized by the generosity she afforded others and how quickly she found humanity in mayhem. Her 1990 anthology, Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black, collected most of her essays, and Semiotext(e) has just reissued an expanded version. The first half of the book gathers the bits of memoir Cookie published in various magazines, followed by a potent batch of “fables,” and then auntie vibes from Cookie the caregiver, acting in her role as health columnist for East Village Eye.

Addiction and madness enter the chat early. Still in her hometown of Baltimore, at fifteen, Mueller has two lovers, one of them Jack, a seventeen-year-old with four years of alcoholism under his belt. She visits him in the hospital and writes, in a little flicker of triplets, that “he didn’t look too good in there, all yellow in a murky blue private room.” Her other lover was Gloria, and, to the world, “we were best girlfriends, both of us with our combustible hairdos, sprayed with lacquer and teased high as possible.” Gloria dies after silicone breast injections go rogue, meaning that Mueller lived an entire Waters movie before she was eighteen.

Baltimore doesn’t last long, as Mueller is “always leaving.” All she shares with her family of origin are “a few inherited chromosomes, the identical last name, and the same bathroom.” She finds her way to Haight-Ashbury in 1967, living not for the last time with upwards of ten people. There, a single day involves almost meeting Charles Manson, definitely meeting Anton LaVey, being harassed in a church, getting raped at gunpoint, and being on LSD for most of it—but her most acute complaint is that the recording of her amphetamine rap session sounds “foolishly cyclical” the day after.

When Mueller comes back from San Francisco, she stays with her parents and meets a “rare bird” named John Waters. “He was born rococo, with perceptions that surely confused his parents,” she writes. The story A24 needs to option first is “Route 95 South—Baltimore to Orlando.” Mueller and her friend, Lee, hitch a ride with Cleo, “a male version of a nouveau-riche hillbilly Farrah Fawcett, way before her time.” The 1960s were very different, so Jascha Heifetz is blasting from the car stereo. Cleo robs houses politely, one after the other, and Mueller tries to pinch a golden statue from his haul in the back seat. (Cleo lets Mueller, a fellow “hoodwinker,” keep it.) The two friends land in the middle of the Okefenokee Swamp, a little less high than normal, giving Mueller time to remind us that she sees more than the people she rumbles around with.

There was no moon. The sky was like black cotton batting that enveloped us in a way that felt like walking through clear water in a pool painted black. Very clear and cloudless was the night sky, so it was thick with stars. We even saw clusters of the dust from exploded supernovas deep in space, thousands of light years away.

Even the shit sparkles when you ride with Mueller, who has punchlines for every disaster. A failed backwoods rape? Cookie sticks to anecdote and dark humor, her quiet way of processing trauma. Her assailant prays to Jesus for a boner, and she bolts. “Not waiting to see whose side the Lord was on, I pushed his wiener quickly aside and threw open the door and dove out into the darkness. I ran faster than I’d ever run and I wasn’t a bad runner.”

She beats every bad case, until the end. At the Berlin Film Festival in 1981, with Amos Poe, Mueller gets stuck with the bloated hotel bill and ditches. She climbs two wire fences and a concrete wall to get to her friend’s flat. Perhaps apocryphally, her German friend is frying sausages and listening to Wagner. Too much? Mueller makes it fly by, to be safe. Her final answer, when asked about her torn clothing and general disarray? “I just climbed the Berlin Wall.”

The memoirist hits hard because the events were real (mostly), but the fables glow brightest on repeated reading. They’re short, some only a page or so, but still manage to extrapolate a universe from the world of the wayward characters we’ve gotten to know in the first half of the book. In “The Third Twin,” a woman lives with her mother and her oxygen tent, a combination that drives her “to the shopping mall every day to escape the sound of breathing.” In the space of a few pages, our narrator, Ioona, meets a man named William Way who “her DNA double helix had uncoiled to make,” and then loses him to an icy lake. When she discovers she is pregnant, “she was finally, after all these years, being included into life’s mysterious order where tranquility’s sweet bloodless arms would envelop her and rock her until the end.” Motherhood was never some kind of trad concession for Mueller. Hell, it’s the original body horror. The other fables include missing toes and missing thighs and women who become fish. And when Mueller writes about a mother, it is someone named Joanna who put her two kids to bed and then “sat down at the kitchen table with a bottle of Remy Martin, the Bible, an ephemeris, an atlas, a calculator and seven grams of cocaine.”

These characters transform believably through states, and the physical diminishments are direct echoes of AIDS, which Mueller wrote about as a health columnist. One brief query about period cycles triggers several pages on AIDS and mosquitoes and bodily fat as the new symbol of health. Mueller’s kicker in this column sounds much closer to what she—go-go dancer and philosopher and mother and prose engraver—brought to the page every day: “Keep your body very strong and don’t forget your sense of humor.”

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York.