Alan Gilbert

Alan Gilbert

In the artist’s show at MoMA PS1, a wanderer in an abandoned airport evokes globalization and displacement.

Naeem Mohaiemen, Tripoli Cancelled, 2017. Digital video (color, sound), 95 minutes. © 2017 Naeem Mohaiemen. Image courtesy the artist and Experimenter, Kolkata.

Naeem Mohaiemen: There Is No Last Man, MoMA PS1, 22–25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, New York, through March 11, 2018

• • •

At the midway point of Naeem Mohaiemen’s film Tripoli Cancelled (2017)—originally commissioned for Documenta 14 and now the centerpiece of the exhibition There Is No Last Man—an unnamed, male protagonist dances to Boney M.’s version of “Rivers of Babylon,” which he plays on an old cassette recorder. This song of perpetual exile—“By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down / Yeah we wept, when we remembered Zion”—is an appropriate musical interlude for a film whose only character (played by Iranian-Greek actor Vassilis Koukalani) wanders the abandoned and decaying Ellinikon International Airport in Athens, where Mohaiemen’s father was marooned for nine days after losing his passport exactly forty years before the film was made.

The dancing figure is seen from afar, framed by the airport’s modernist interior (much of the film is set in a terminal designed in the 1960s by Eero Saarinen, architect of the famous TWA Flight Center at New York’s JFK airport). Shot by Petros Nousias, Tripoli Cancelled frequently employs long takes, both spatially and temporally; not only do viewers watch Koukalani dance in the distance, they watch him for the entire four-plus-minute song with no edits or changes in perspective. This is in keeping with the pace of the ninety-five-minute film. During extended periods, featuring ambient noise, the camera closely follows its character through the airport’s empty rooms, up and down stairs and escalators, or out onto the runway. Other times, he is portrayed small within the vast architecture that encloses him, as happens during his dance. In both instances, the film’s intelligently choreographed exchange is between individual autonomy and larger structures—and suggests that much of freedom might actually be an illusion.

Naeem Mohaiemen, Tripoli Cancelled, 2017. Digital video (color, sound), 95 minutes. © 2017 Naeem Mohaiemen. Image courtesy the artist and Experimenter, Kolkata.

Despite the seeming soberness of this cinematic structure, Koukalani’s dance is joyous, as is the “official” video for Boney M.’s “Rivers of Babylon,” which is striking for a song that is ultimately about slavery: “When the wicked / Carried us away in captivity . . .” Tripoli Cancelled is not about slavery, but the use of the song is hardly coincidental, given the film’s Athens location: along with the autobiographical connection, Greece was in certain ways ground zero for the European debt crisis of 2009, which resulted in the shredding of the country’s social safety net in order to become eligible for global finance’s bailout loans. Greece has also been a primary destination for refugees from the Middle East, with over a million entering the country between 2015 and 2017, the majority in that initial year.

More than contextual, these concerns with family, globalization, and displacement inform the film, which is broken into seven days of the week, from a Monday to a Sunday. In Koukalani’s voiceover, the protagonist narrates a letter to his wife each day; in the first, he says that more and more refugees are arriving, even though he remains completely alone for the entire film and appears to have no contact with the outside world (Ellinikon Airport was in fact temporarily used by the Greek government to house refugees). From one perspective, Tripoli Cancelled might be about a man of Middle Eastern descent with brown skin wandering the ruins of Western civilization—or neoliberalism’s wasteland—in Athens, its fabled birthplace, except that Mohaiemen has titled his exhibition There Is No Last Man. Given the desolation of the setting—empty yet not in ruins—viewers might be tempted to assume that a catastrophic event has previously taken place, destroying or scattering the population.

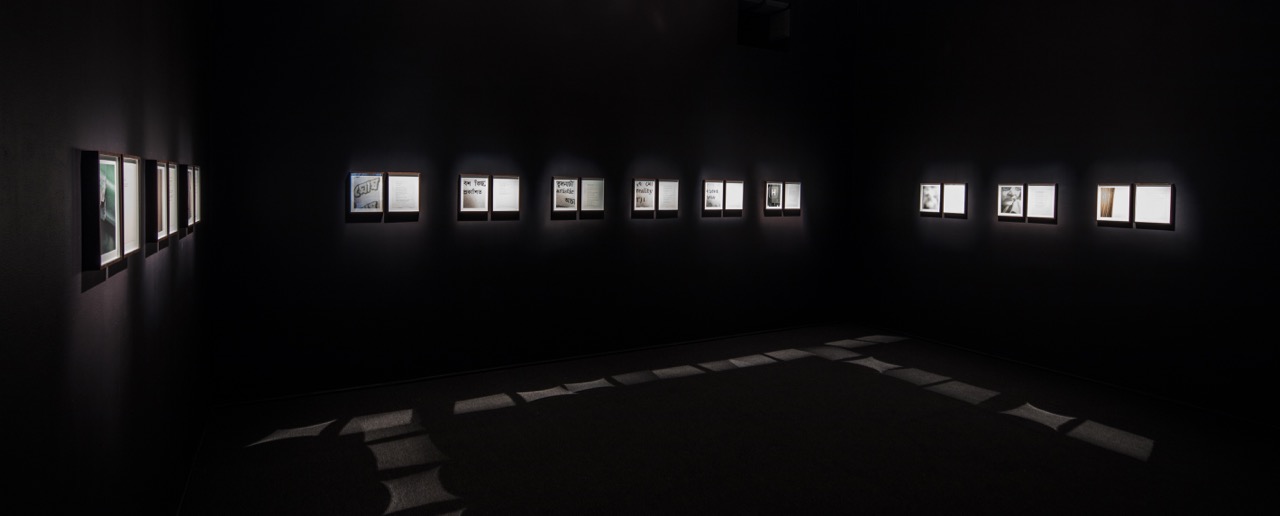

Naeem Mohaiemen: There Is No Last Man, installation view. Image courtesy MoMA PS1. Photo: Pablo Enriquez.

Tripoli Cancelled begins on “Monday, Day 3753,” which would seem to indicate that the protagonist has been stuck, trapped, or exiled within the airport for more than ten years. He passes his days with a combination of mundane and whimsical activities: shaving, smoking, eating food from a can, composing letters in his head, reading aloud passages from Richard Adams’s 1972 novel Watership Down, as well as pretending to fly an airplane, to work as an air-traffic controller, and to order a soda water at the bar. He sings a song near the end of the film in which he says that on Sundays he only wants to rest, as the Judeo-Christian God is described as doing in the Old Testament at the end of creation. This might lead viewers to think that his entire situation, which is his entire world, is his own omnipotent fabrication. Yet this is only one of Tripoli Cancelled’s various metaphorical inflections, which also address disaster, loss of home, as well as a sense of hope contained within the playful imagination. The beauty of Mohaiemen’s film resides—at the level of both form and content—in this quiet open-endedness.

Naeem Mohaiemen: There Is No Last Man, installation view. Image courtesy MoMA PS1. Photo: Pablo Enriquez.

Accompanying Tripoli Cancelled at MoMA PS1 is Volume Eleven (flaw in the algorithm of cosmopolitanism) (2016), a series of twelve image-text diptych prints in dialogue with the Bengali writer Syed Mujtaba Ali (1904–74). A chronicler, archivist, documentarian, and activist over the past fifteen years through his work as a video- and image-maker, Mohaiemen was translating short stories by Ali, who is his great uncle, when he discovered that Ali had written a handful of essays in support of Nazi Germany. This was not uncommon among certain South Asian intellectuals of the time, who reasoned that a German victory in the war would terminate British colonial rule over India, although many—including Ali—soon became disillusioned with Nazi ideology. Mohaiemen is horrified by his discovery, which he explains over the course of the twelve prints in descriptions resembling poetry, right down to the line breaks and short strophes. He further discusses relations between Hindus and Muslims, India and Bangladesh (Mohaiemen was raised in Bangladesh, and now lives in New York), and lighter and darker skin among Ali’s relatives, and what this means for passing—and for opportunity—in Western countries. While the photographs in Volume Eleven are mostly close-ups of Bengali and English books from Ali’s library, or isolated words from them, Mohaiemen’s text—like the narrator’s letters to his wife in Tripoli Cancelled—is poetic, figurative, and approaches history expansively while remaining rooted in family and contested territories.

Alan Gilbert is the author of two books of poetry, The Treatment of Monuments and Late in the Antenna Fields, as well as a collection of essays, articles, and reviews entitled Another Future: Poetry and Art in a Postmodern Twilight. He lives in New York.