Ben Ratliff

Ben Ratliff

The return of penguins in bondage! Taking stock of the controversial musician through a new box set.

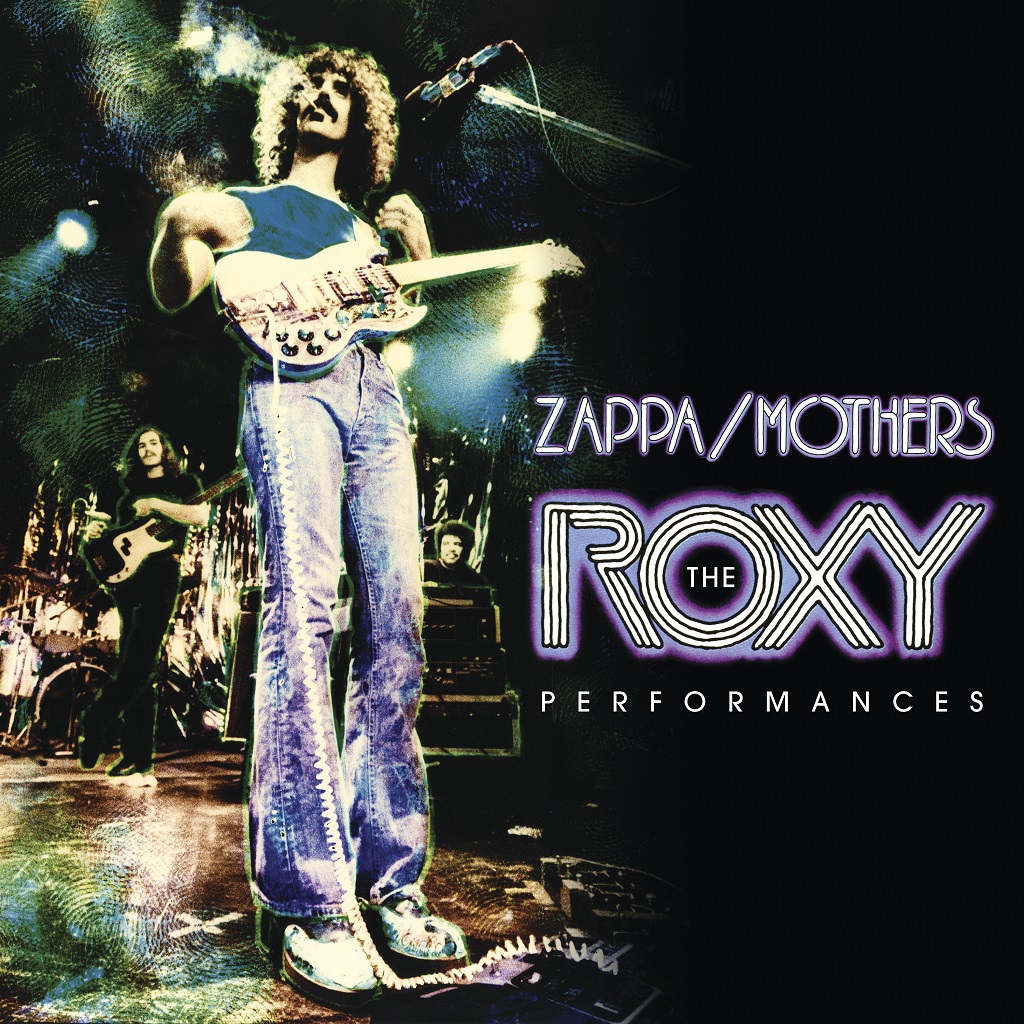

Frank Zappa, The Roxy Performances, Zappa/UMe

• • •

Several weeks ago on The Best Show, Tom Scharpling’s weekly online radio program, the prompt for listener commentary was “I love it and I hate it.” Yes, please. It’s a useful emotion, healthier than its self-negating cousin, guilty pleasure; it keeps the receptors open. Those who called the show kept it frustratingly light. They talked about exercising, Star Trek, Oreos. I didn’t phone in, but my first thought was The Best Show itself. My second thought was Frank Zappa’s music in late 1973, once released as a double LP called Roxy & Elsewhere, and just expanded for a seven-CD box set called The Roxy Performances.

Zappa, who died in 1993 at fifty-two, was a protean composer-improviser-bandleader, and this was his most representative music by his best band. It is fussily complicated and swinging, shaped by the non-resolving clangor of midcentury European composers like Boulez and Messiaen and the American vernacular of blues and soul. It is time-wastingly puerile and sometimes moving. It is central to the current, West Coast, jazz-and-hip-hop-adjacent sound worlds of Thundercat and Kamasi Washington, and in other ways it seems to have sunk to the bottom of the ocean. It bristles with control and beams outward with serenity. It is a sort of miracle, a broad vision with noble execution, and it is sometimes unbearable. Zappa remains an and proposition, not an either/or one. Committed ambivalence is the way to go with him.

Frank Zappa and band at the Roxy. Image courtesy the Vault.

This is a record suggesting a sense of time and place: December 8, 9, and 10 in 1973 at the Roxy Theater in West Hollywood. The music from the Roxy—to some extent on the original LP, which added emphasis and color to the arrangements in post-production studio touches, but more so now in its full and undoctored form—is beautifully recorded, which is to say you can feel something resembling the dimensions of the room. His band was an octet that reduced into pairs and, sometimes, paradoxes. It contained: two singers and instrumental soloists, one meticulous and one blurry, Zappa (with his electric guitar) and Napoleon Murphy Brock (with his tenor saxophone). Two trap-set drummers, Ralph Humphrey and Chester Thompson, who played patterns either in grooves with complementary detail, or in cold lockstep. The Fowler brothers—Bruce, a trombonist with flow and vigor, and Tom, on electric bass, who gripped into the details without overplaying. George Duke, a swinging and virtuosic keyboardist from the intersection of jazz and soul, and Ruth Underwood, a classically trained non-improvising percussionist, who stamped out the music’s composed lines for electric marimba, xylophone, and vibraphone with precision and grace.

Zappa, who made his first record in 1966 (Freak Out!), could turn out high-functioning bar-band rock with ease, like many bandleaders who worked widely in the last days of live music’s dominion, before DJs essentially took over nightclub culture. But wherever there is the most compositional rigor in these late-1973 songs—where they declare themselves as separated from rock and roll by sound and technique but adjacent to it by intensity and conscience—Underwood is there at the spine of the music, doing extraordinary things. (She toured with the group for two years, until the end of 1974.) Zappa is commonly known as a guitar player, but he started as an orchestral percussionist. If that’s surprising from a distance, it isn’t when you hear this record. Make your own breakdowns and bracketology about the strengths of The Roxy Performances, but to me this box set seems a monument to Ruth Underwood.

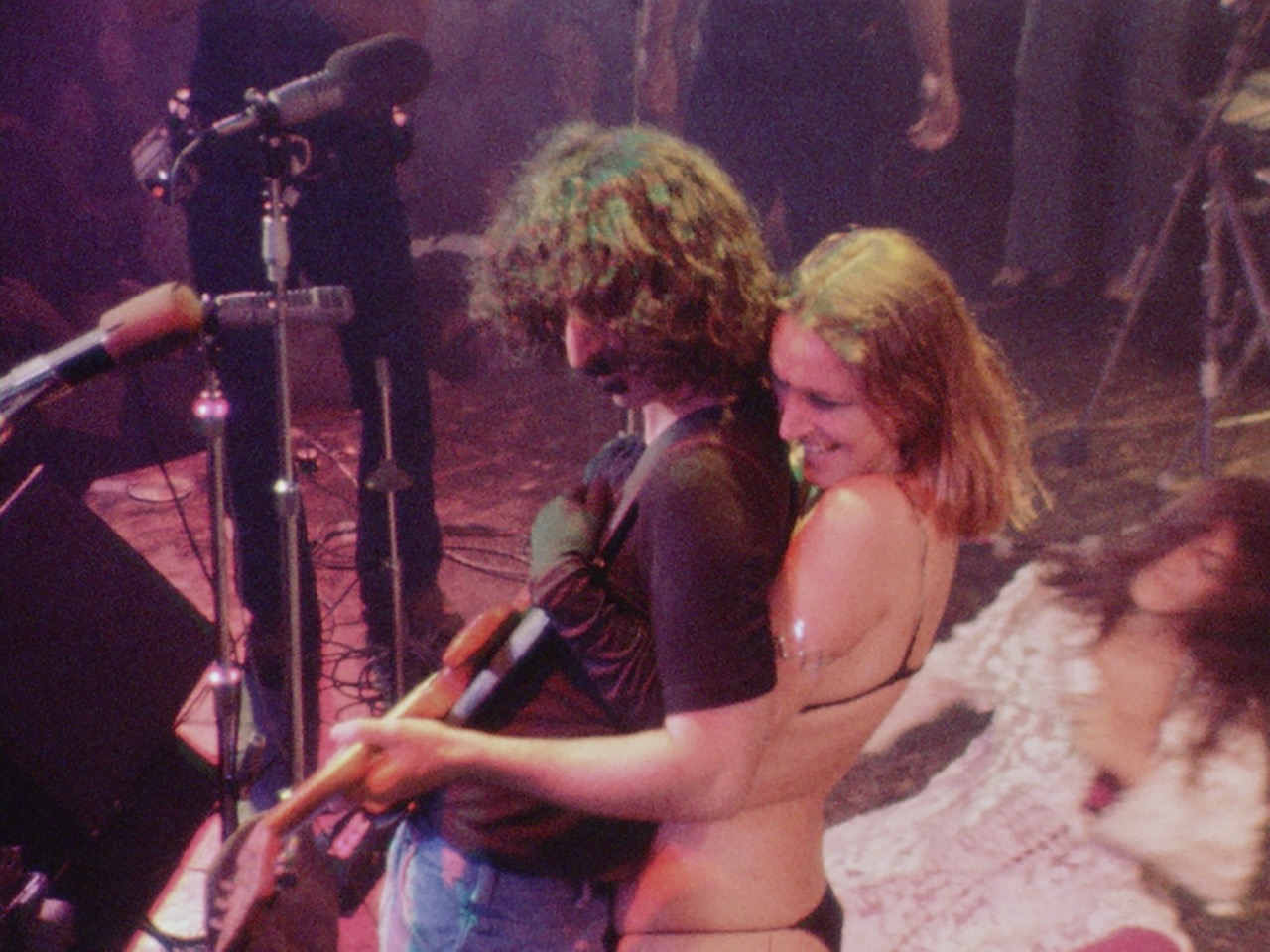

Frank Zappa at the Roxy. Image courtesy the Vault.

For some people—and for me—Zappa’s words are the first barrier to loving his work. In songs from The Roxy Performances like “Penguin In Bondage,” “Dickie’s Such An Asshole,” and “Cosmik Debris,” the lyrics are dour and high-handedly ironic. Zappa’s lyrics at the time were full of lazy-undergraduate dick jokes, groupie jokes, sex-toy jokes, Nixon jokes in glib-hip narrative form. He was about half a surrealist and a full defender of the First Amendment. And he deemed groupietude to be “one of the most amazingly beautiful products of the sexual revolution” (this is detailed in the documentary Eat That Question, a 2016 supercut of his interviews through the years). And he was the kind of guy who could stand behind any number of dumb lines like “the price of meat has just gone up / and your old lady has just gone down,” in “Cosmik Debris,” because, presumably, he was using irony.

This part of Zappa can be defended, of course. Frank Zappa: The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play, a 1994 biography by the English Marxist writer Ben Watson, enlists Adorno as a kind of cosignatory for nearly everything Zappa ever did or said. George Orwell might have appreciated Zappa’s humor the same way he liked rude English pulp postcards in his 1941 essay “The Art of Donald McGill.” A lot of male Zappa fans under seventeen haven’t had a problem with it.

If you had a middle-class shock threshold, though, Zappa would test it. (He still can.) He surely felt a lot of social norms were dumb, but he also seemed to feel that a lot of rebellion was dumb. He played and composed, but he also disapproved for a living. As a kind of pop star, he used irony and critiques of commodity culture as a mild form of torture; he could do it all day. And at the same time, this box set also includes three different versions of “Village of the Sun,” which sounds like an early-1970s Isley Brothers deep cut with twice as many chords. Sung by Napoleon Brock, it’s a message of approval; it portrays Sun Village, a real town near Zappa’s high school in Southern California’s Antelope Valley, an African American community where he played gigs as a teenager with his mixed-race band. It reflects that small society’s approval of Zappa, the terminal outsider, as much as his approval of it. It is almost an Edenic vision.

But the music is so much more worthwhile.

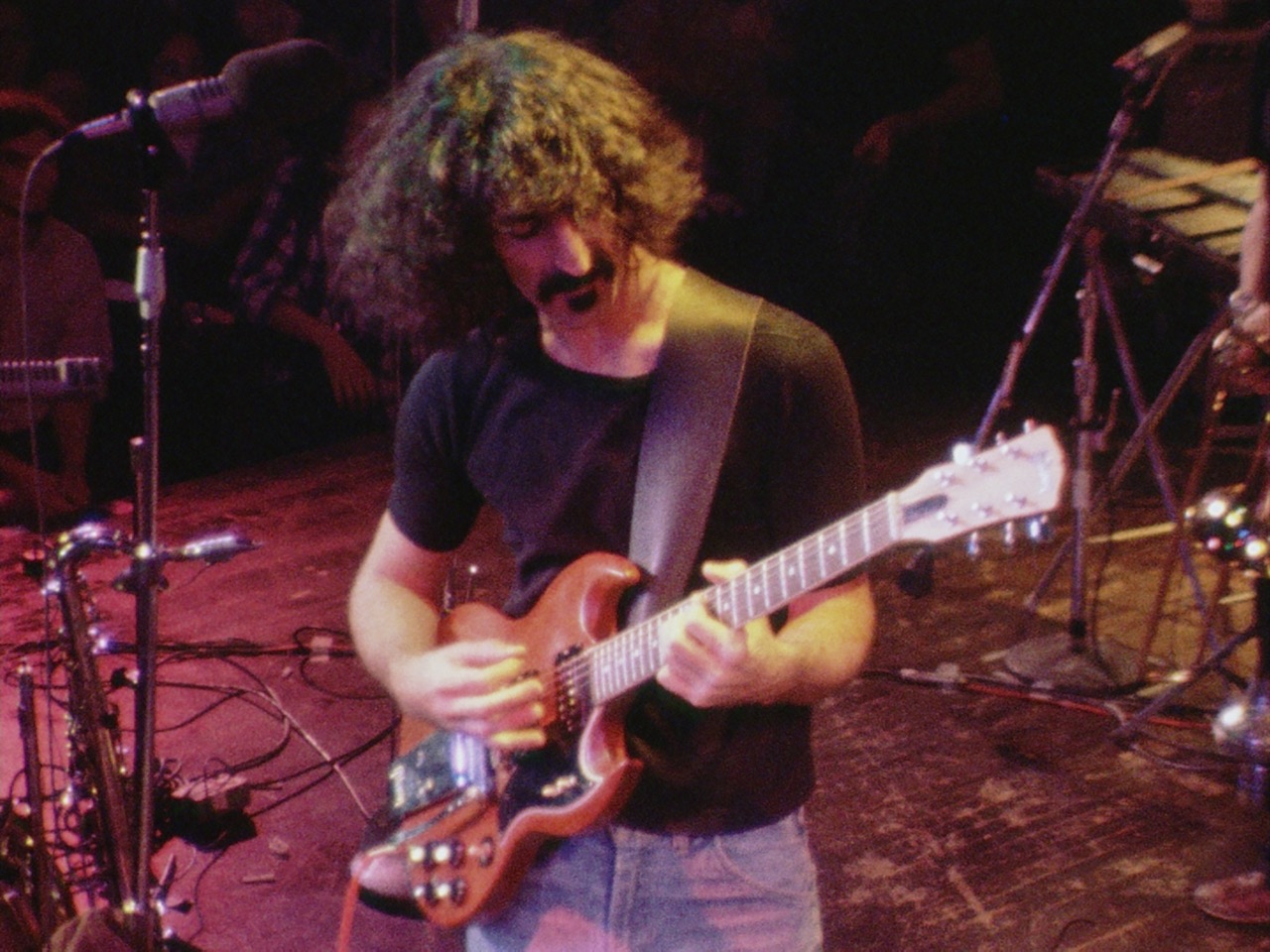

Frank Zappa at the Roxy. Image courtesy the Vault.

The songs on Roxy come in some kind of blues form (like “Penguin in Bondage”) or ferociously percussive modernism, but the miracle is that they are integrated: you don’t have to choose. They are both. The most literal example of this is the switching between 4/4 and 5/16 in “Echidna’s Arf (Of You),” which sounds like a clinical trick even in my description, but comes off simply as what the song needs to do, its inner essence externalized. There is a warmth in this music, even at its most involuted, and Zappa’s long guitar solos on the Gibson SG—luxuriating in the lower and middle registers, bunched into rapid and backward-sounding phrases against the meter, their tone compressed through careful and minimal applications of a wah-wah pedal—form a discourse with such immediacy and cohesion that they need not stop where they do.

The story of Zappa’s music, from 1966 to the end, seems to me a progression from joy in its execution—Freak Out!, as much as it is postmodern and ironic and all that, is joyous—to a narrower satisfaction in its aim and arrangement. The Roxy Performances seems to be a break in this progression, or perhaps the exact middle point.

Ben Ratliff is the author of four books, including Every Song Ever.