Leo Goldsmith

Leo Goldsmith

Arson, male pathology, and a little bit of Gatsby: a new film from Korean director Lee Chang-dong.

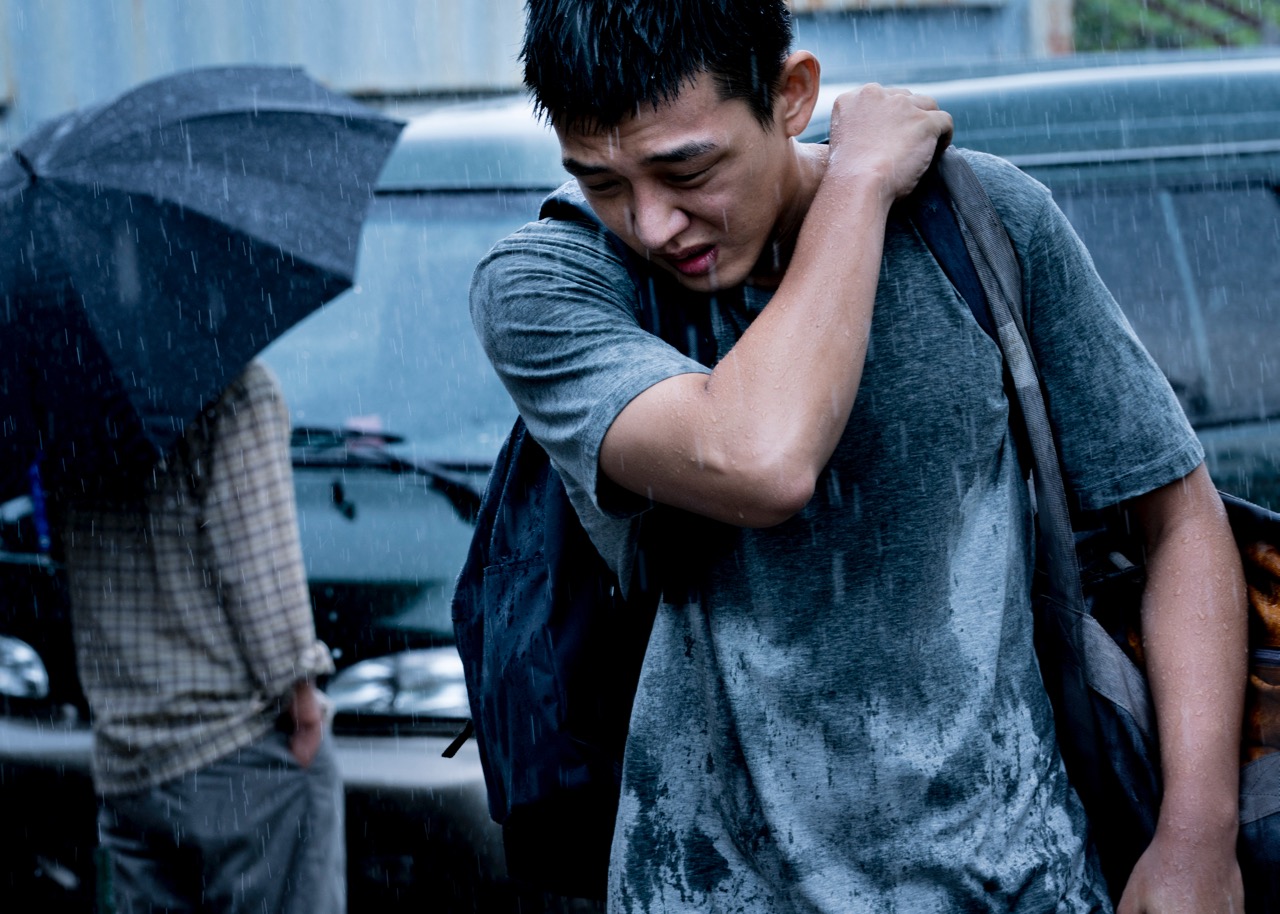

Yoo Ah-in as Jongsu in Burning.

Burning, directed by Lee Chang-dong

• • •

Burning is a film adapted by the award-winning Korean director Lee Chang-dong from a short story, “Barn Burning,” by Haruki Murakami, which in turn shares its title with another story by William Faulkner. Indeed, something of this lineage is suggested in a brief scene that occurs about halfway through Lee’s film, in which one character—suspiciously handsome rich boy Ben—queries dopey wannabe writer Jongsu about the latter’s favorite authors. Without a great deal of thought, Jongsu responds, “Faulkner,” because he feels the great American author’s prose relates back to him something of his own experience. It’s an amusing line, and not only because it alludes to the film’s pedigree. Unaccomplished and unremarkable, Jongsu is the type of young male writer who, if he gets around to writing at all, is bound to write only about characters that resemble himself: dopey wannabe writers.

Jongsu (Yoo Ah-in) is that type sub–par excellence: he is perpetually open-mouthed, seems confused by girls, and has issues with his parents. We encounter him in the middle of what must be a long series of shit jobs, as delivery boy for an ugly discount store. This is where he meets—or re-meets—Haemi (Jun Jong-seo), a former classmate he doesn’t recognize, perhaps owing to the cosmetic reconfiguration she says she’s undergone. She now keeps her credit card debt at bay by working as a midriff-baring barker for the store’s endless “BLOWOUT SALE.” They reconnect over a cigarette, and soon, following some fumbling sex in her tiny apartment, Haemi has roped Jongsu into minding her possibly nonexistent cat while she escapes for a trip to Africa.

Jun Jong-seo as Haemi in Burning.

This is where she finds Ben—alluringly dodgy Ben, played by the Korean American actor Steven Yeun—a figure who elicits all of Jongsu’s barely veiled insecurities. From the moment he picks Haemi and, unexpectedly, Ben up from the airport in Seoul, it is unclear who Jongsu pines for more: his pseudo-girlfriend or the slick rich guy who steals her away from him. Of course, part of the attraction for Jongsu is that he is painfully incapable of understanding either one of them. Haemi seems to him mysterious, but perhaps she is just wifty. She might be a cunning manipulator, but she’s more likely a victim—of what, Jongsu is not precisely sure. And Ben—Gatsby-like, as Jongsu himself points out, and cavalier—how does he make his money, exactly? Is his boast that he has never cried even once in his life a sign of “superior DNA,” or of sociopathy? Even when Ben divulges—while sharing a joint with Jongsu and blasting Miles Davis from the stereo in his Porsche—that he has a fondness for burning down greenhouses, we are not sure how to take it: as a sign of perverse megalomania, a spoiled rich kid’s reckless affectation, or as a reference to Faulkner?

Steven Yeun as Ben in Burning.

What’s impressive here is the way Lee, as in his previous films, deftly mixes a sense of immediacy with a tremulous undercurrent of menace and uncertainty. The movie plays with elements of satirical comedy, issue-picture, and, eventually, mystery-thriller, but we’re never quite sure what genre we’re in. Staples of Lee’s cinematographic repertoire—an interest in natural light, precise focus, a roving handheld camera—seem to promise brute realism, but there’s always the eerie ambivalence of an unidentified point of view. And this is crucial to a style that tends to place us alongside characters whose grasp of present reality is, to say the least, wobbly. In this sense, Jongsu seems to live in the same liminal headspace as the protagonists of Lee’s earlier films: the daydreamers in Oasis (2002), the grief-stricken Christian convert in Secret Sunshine (2007), and the demential grandmother in Poetry (2010).

What Lee has often done best is to tether this sense of ambiguity to the particularities of contemporary Korean society. Indeed, in updating Murakami’s extremely brief story, he has reinstalled a crucial element from Faulkner’s original. There, the propensity toward arson—and apparent antipathy toward barns—is firmly rooted in class. The young protagonist’s destitute sharecropper father, racked with poverty-fueled rage, incinerates the barns of those who insult him. Lee’s protagonist has an angry dad, too—he’s in custody for the film’s duration for assaulting a police officer. But, here as in Murakami’s story, the pyromaniac is the protagonist’s mysteriously affluent competitor. Burning is, for Ben, more an assertion of privilege than an attempt to exorcize accumulated humiliations.

Steven Yeun as Ben in Burning.

Nevertheless, it’s something of a pity that a work so precisely constructed as Burning too often devolves into yet another male-insecurity movie. Indeed, this theme is especially tired within the world of contemporary Korean cinema, which, since its reemergence in the mid-1990s, has been obsessed with masculinity as something imperiled, as something to be mulled over, as something to be either challenged or fortified—or challenged, then fortified. The sadistic misogyny of turn-of-the-millennium “Asia Extreme” films like Kim Ki-duk’s The Isle comes to mind, as does Hong Sang-soo’s endless, but at least evolving, parade of sad-sack pseudo-artist losers. Not for nothing was one of the first major scholarly studies of new Korean cinema, by Kyung Hyun Kim, titled The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema (2004). Here, as everywhere, culture is constantly being tasked with reinscribing manliness into the national narrative.

Yoo Ah-in as Jongsu in Burning.

What’s even more disappointing is that, in Burning’s immediate predecessors, Lee seemed to have pivoted away from allegorical treatments of Korean manhood. His previous two films, Secret Sunshine and Poetry, explore women characters whose narratives don’t necessarily echo Big Historical Events like the North-South division, the fallout of the 1990s financial crisis, or the military dictatorship. Burning seems an emphatic return to this territory, dwelling intently on male pathology at the level of character psychology and signposting its connections to the problems of the day. As if to pin the film’s central conflicts to precise geographical coordinates, Ben’s palatial apartment is located in the famously chic Gangnam district—yes, the neighborhood from that ubiquitous K-pop jam from 2012—while the family home in the country to which Jongsu is relegated is a mere stone’s throw from the Demilitarized Zone, with the Democratic People’s Republic both visible and audible from his driveway. (“How fun,” says Ben.)

Similarly, it’s hard, in this precise historical moment, to miss the import of a shot in which a TV reporter blathers something about “youth unemployment” while Jongsu urinates in the background. (To remind us that toxic masculinity is indeed global, Lee also gives us a glimpse of the unmistakable keratinous visage of the American president.) Perhaps it’s an index of Jongsu’s blinkered perspective, but it’s curious that Haemi and her own class and gender burdens seem of so little concern to the film. She remains, rather tediously, an enigma—and a topless one, too, dreamily dancing to the jazz wafting from Ben’s sports car.

Leo Goldsmith is a writer, teacher, and curator based in Amsterdam and Brooklyn. He writes about art and film for such publications as Artforum, art-agenda, the Brooklyn Rail, and Cinema Scope.