Leo Goldsmith

Leo Goldsmith

From Attica to Alcatraz: a film series explores the carceral state.

Prison Images. © Harun Farocki, 2000.

“Prison Images: Incarceration and the Cinema,” Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, New York City, June 20–July 8, 2019

• • •

“Who is the spectacle for?” Harun Farocki’s 2000 film Prison Images asks. Here, the “spectacle” refers to those images produced inside the prison walls, images that record the prisoners’ every movement through surveillance systems, spyholes, and gun-mounted video cameras. These images, Farocki notes, put the prisoner continually on display, but are meant for a limited audience. Usually, the prisoner is intended to be invisible. Execution and torture are no longer public events for community entertainment; contemporary prisons, now more frequently located in deindustrialized hinterlands than in urban centers, hide the bad element from sight. And yet, the voyeuristic impulse to see the prisoner remains.

Cinema’s attraction to the prison is long established and often, frankly, a bit basic. The prison’s seemingly unavoidable metaphors for all kinds of confinement and control, and its readymade dramatic arcs (the testing of the human spirit, the establishment of social-Darwinist pecking orders), make it as indelible a cinematic topology as the frontier or the battlefield. As a setting, the prison comes with its own miniature theaters, too: the visiting room, complete with telephones and Plexiglas carrels; the yard, invariably dusty; the cell, on view like a peep-show cubicle.

Anthology Film Archives’ series “Prison Images: Incarceration and the Cinema” explores all of these cinematic spaces, but it also suggests a wider perspective, interrogating the fascination with images of incarceration even as the prison itself exists, at least for many, out of immediate sight. The retrospective’s timing is especially auspicious, coming at a moment of intensified mobilization around the problems of mass incarceration and over-policing, and an increased interest in radical solutions, such as the prison abolition movement. Given the evident paradoxes of what scholars have called “the carceral state”—including the steep escalation in rates of imprisonment and law-enforcement budgets, even as crime rates have been dropping for decades—the time is ripe to reconsider the ways in which cinema has rendered the penitentiary and its effects visible.

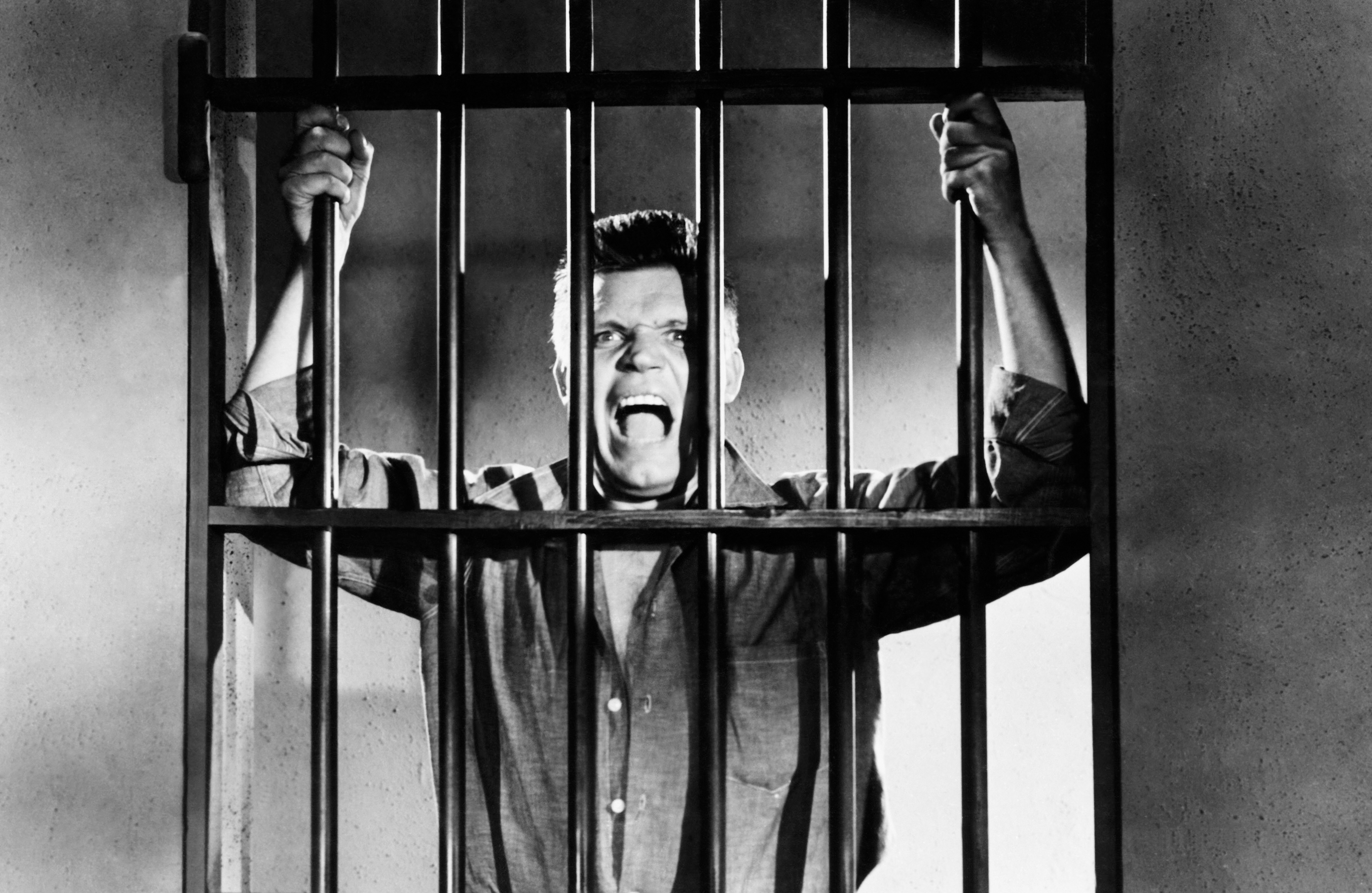

Riot in Cell Block 11. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

In a lot of films, the very act of visualization can serve a radical function, as in the many fictionalized accounts of highly publicized, ripped-from-the-headlines events. Don Siegel used actual locations for his prison diptych: the grim, sweaty Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954), which was shot at Folsom State Prison and fuses elements of the social-realist docudrama and the police procedural, and his rather more hopeful Escape from Alcatraz (1979), which casts Clint Eastwood as famed Rock-breaker Frank Morris, shot within the decaying walls of the island prison itself, not yet a tourist attraction.

Escape from Alcatraz. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

These movies offer glimpses into the carceral space under the guise of popular entertainment; documentary films have often wrestled with providing more direct views. In France, during the post–May ’68 crackdowns, which flooded prisons with the militant left, access to prisons by members of the press was heavily restricted, prompting the philosopher Michel Foucault and a number of his renowned friends and colleagues to found Le groupe d’information sur les prisons (GIP). The group interviewed prisoners and their families, distributed pamphlets, and also produced an important documentary film, Les prisons aussi (1973), directed by Hélène Châtelain and René Lefort, which sought to shed light on the wave of prison uprisings in France between 1971 and 1972. These efforts proved instructive for the radical left in France, forming the ground for an emergent solidarity between political prisoners and common criminals, aligning the prison struggle with the class struggle.

In the United States at this time, the understanding of the deep linkages between incarceration, poverty, and race most fully crystallized around the 1971 uprising at the Attica Correctional Facility in western New York. Attica’s ghosts haunt a number of films in the series, including of course Cinda Firestone’s extraordinary 1974 documentary Attica, which begins in medias res, with the uprising already underway and the brutal reprisals speedily, almost inevitably, descending. The rush of the film derives from this present-tense engagement with the occupation as it unfolds—a temporal alignment that Firestone cruelly interrupts by reminding us that the figures we see onscreen, passionately pleading their cases, would be dead within days.

Child of Resistance. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

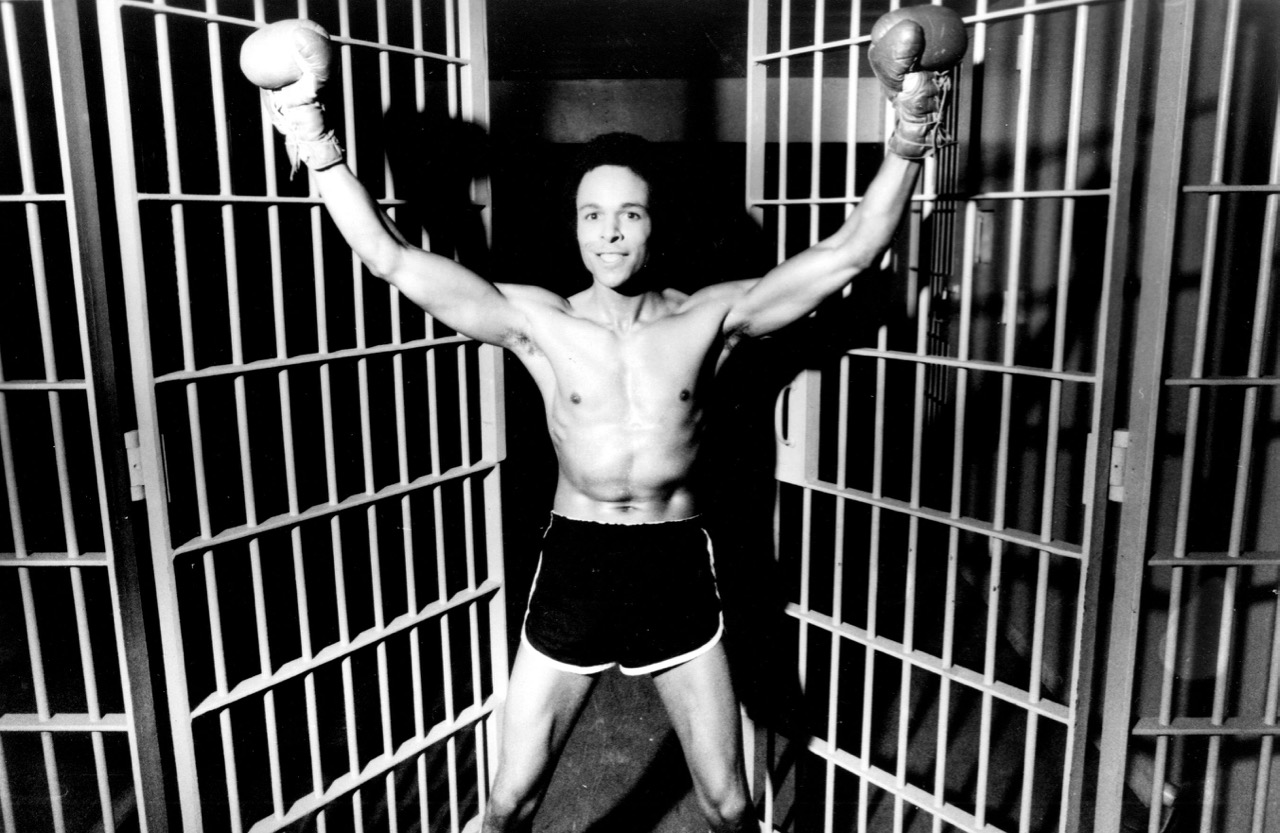

The events at Attica also impressed themselves on the young UCLA film students of the LA Rebellion: here represented by Haile Gerima’s enraged Child of Resistance (1973), apparently inspired by a dream Gerima had after seeing an image of a shackled Angela Davis, and Jamaa Fanaka’s more commercially oriented Penitentiary (1979). In its depiction of oiled-up black bodies pitted against one another in the most abject form of social hierarchization, Fanaka’s film sustains a series of critical comparisons between slavery and incarceration, even as it maintains a lurid, sequel-spawning tone.

Penitentiary. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

As Farocki notes, “Even films critical of prisons wish to be entertaining,” and this may be seen as part of the problem. Prisons make for dynamic, photogenic settings, but their onscreen presence can distract from the social and material conditions that make them possible in the first place. A consideration of incarceration’s expanded field, Brett Story’s The Prison in Twelve Landscapes (2016) documents the vast infrastructure that exists beyond the prison’s walls and the way it helps maintain systems of property ownership, unemployment, and debt. Indeed, while “the prison thriller,” for all its utility, tends to exploit the prison for its gritty realism and grand metaphorical content, the genre usually fails to capture incarceration’s hidden pervasiveness in contemporary life, and even its banality. In this regard, Laurie Jo Reynolds’s warmly funny 2007 video Space Ghost, organized around a series of collect calls from the artist’s incarcerated brother and a cache of trash TV and telephone-hold Muzak, wittily builds an analogy between prisoners and astronauts: both are siloed in artificial enclosures that demand isolation and boredom, and both are subject to physical atrophy and weird food.

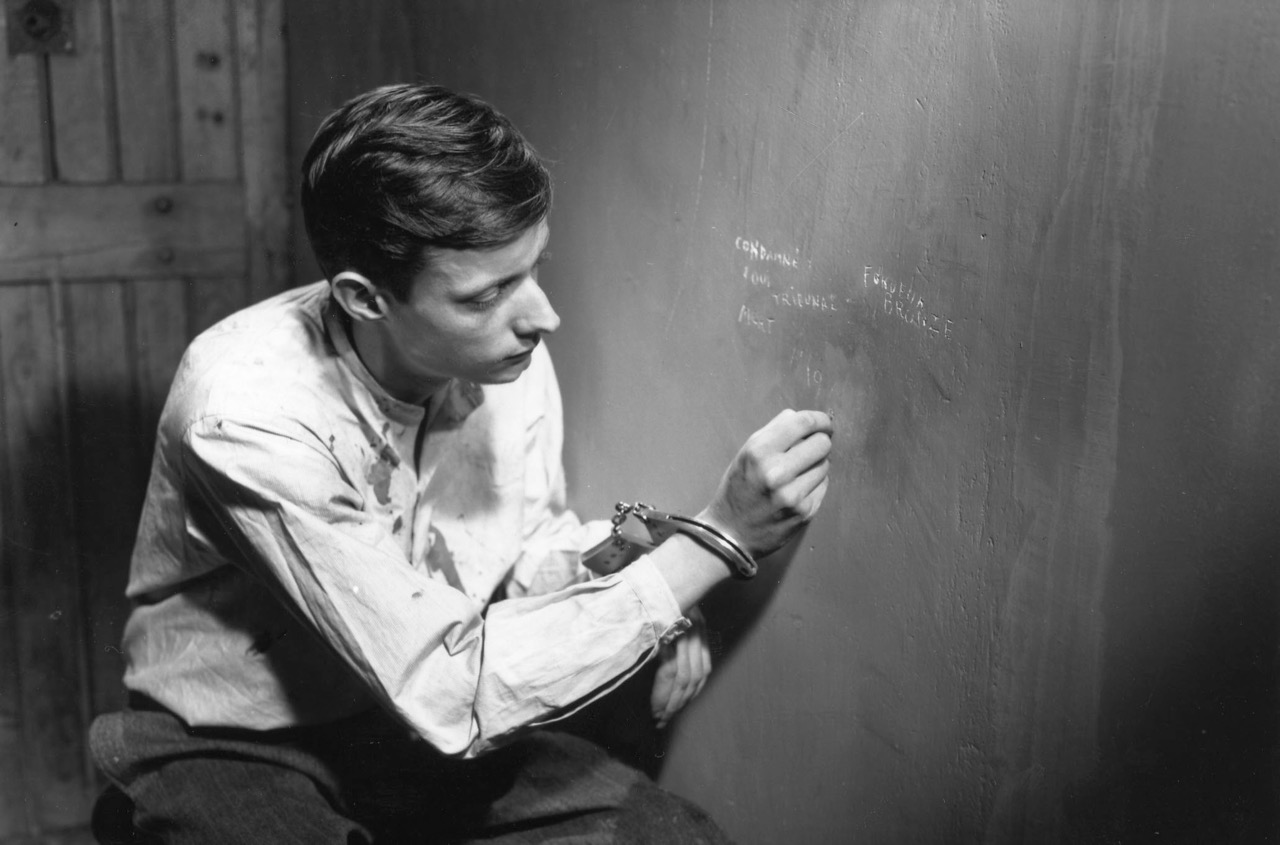

A Man Escaped. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

While Reynolds’s images of prison are sourced entirely from bad television news, her video nonetheless depicts the prison not simply as a building, but also as a network of social relations that extends far beyond its walls. In this way, films about incarceration also function as a means of considering new types of social formations. This is the teasing possibility of Jean Genet’s Un chant d’amour (1950), which casts the prison both as a space of voyeuristic control and oppression and as an emergent queer utopia of armpits and unruly hard-ons, a site in which human intimacy will be attained at all costs: an exhalation of cigarette smoke blown via a straw through a hole in the concrete wall and into the lungs of the inmate in the next cell. Almost certainly inspired by Genet’s film, Robert Bresson’s exquisitely precise A Man Escaped (1956) finds a similar oasis, constructing the prison from a series of abstracted gestures, signs, and noises, and building between the prisoners a vision of solidarity that is, like Genet’s, deeply corporeal.

Terminal Island. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Less classically, Roger Corman protégée Stephanie Rothman’s Terminal Island (1973) depicts an imaginary prison that’s rather more like the setting of an episode of Naked and Afraid than the usual concrete-and-iron edifice. The prison’s inmates—including a bearded Tom Selleck, Lost in Space’s Marta Kristen, and the underappreciated Ena Hartman as an Angela Davis surrogate—are marooned on the cay of the title, which is surrounded by policed waters and sea mines. But for a bit of offhand boobsploitation, Terminal Island offers a fairly serious disquisition on the question of how to remake society from scratch: either under the iron-fisted rule of a tyrant or through collectivization and equal rights. Even at their most exploitative, then, these films make possible the consideration of the prison not as a mere site of confinement and punishment, but as a place in which to imagine a different kind of society, perhaps one in which the prison itself no longer exists.

Leo Goldsmith is a writer, teacher, and curator based in Brooklyn. He writes about art and film for such publications as Artforum, art-agenda, the Brooklyn Rail, and Cinema Scope.