Ratik Asokan

Ratik Asokan

Nabarun Bhattacharya’s scabrous cult favorite gets a new

English translation.

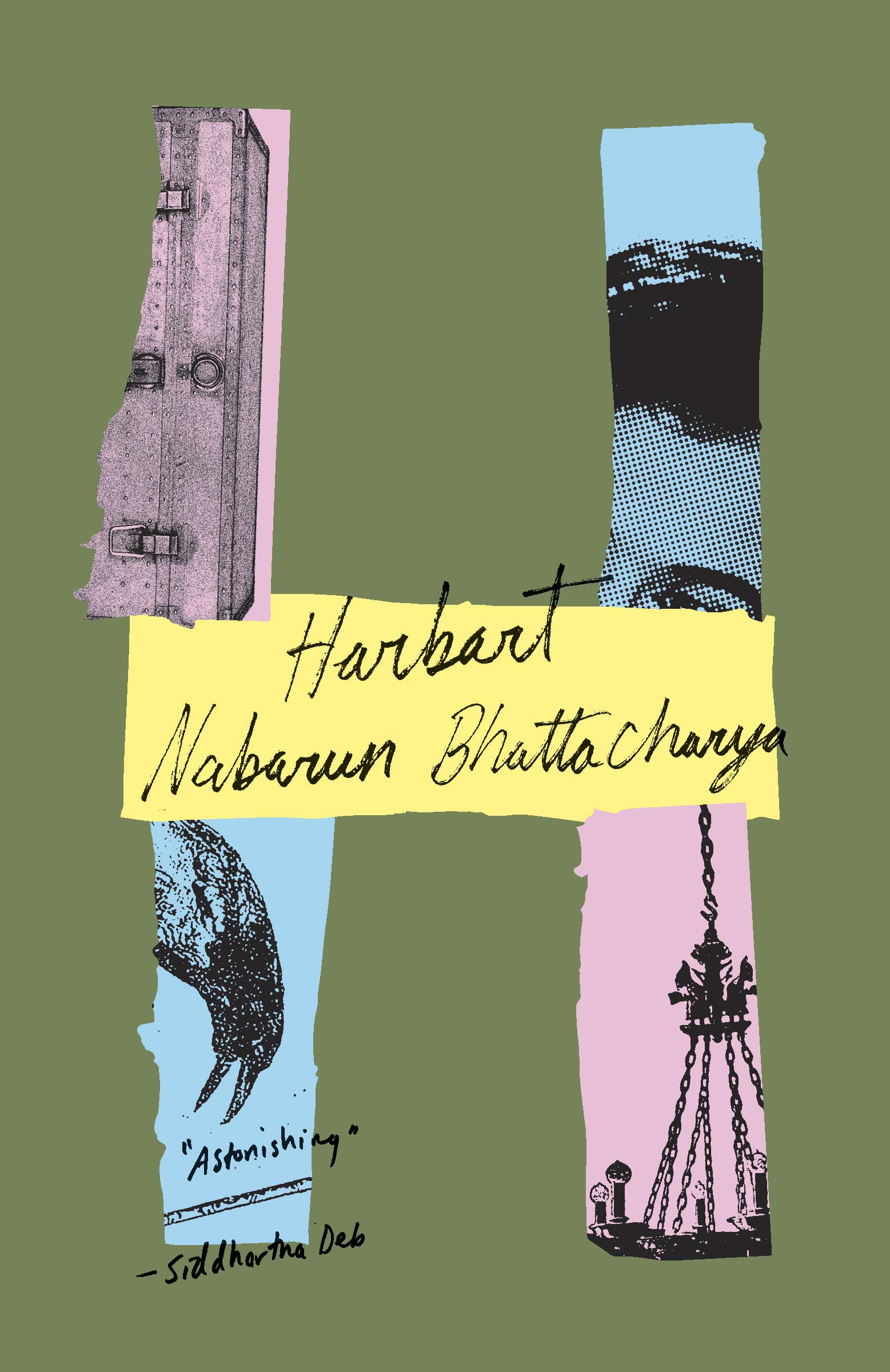

Harbart, by Nabarun Bhattacharya, translated by Sunandini Banerjee, New Directions, 122 pages, $13.95

• • •

Even right-wing economists now express concern about the levels of inequality in India. Ever since the early ’90s, when the country’s markets were opened up to international capital, a wedge has been growing between a small, upwardly mobile minority—mislabeled the “middle class”—and a vast laboring underclass, a wedge so large today that it beggars belief. In 2017, the last year for which we have reliable figures, the top one percent took away over three-quarters of the national income, while the bottom half saw no effective increase in their wealth. There are still swathes of India where malnutrition is endemic. Yet this is a country that now boasts the fastest-rising number of millionaires on Earth.

Few artists have chronicled this dismal modern period, dubbed “India’s New Gilded Age,” with greater courage than the late Bengali writer Nabarun Bhattacharya (1948–2014). In a brief, prolific career, Bhattacharya returned obsessively to the festering social ills of his country, particularly its manufactured squalor and the arrogance of its neocolonial elite, which he saw as his moral duty to denounce. On more than one occasion he compared literature to political militancy (in his youth, he was involved with the far-left Naxalite Movement). His diverse body of work—ten novels, as well as a stream of poetry, short fiction, and essays—amounted to a protracted guerrilla battle against the neoliberal Indian state.

Bhattacharya wrote about those the emerging new order left behind, mainly the urban poor, whose street-Bengali made its way into his own inventive prose, which more than a few conservative critics found vulgar. Yet he was also a fizzing and playful writer, with a serious interest in literary history, and formal passions that took him far beyond humdrum realism to the shores of fantasy, thriller, and farce (among the recurring characters in his fictional universe are the fyatarus, a troupe of flying beggars; choktars, slum-dwellers who attack the police in tiny flying saucers; and Baby K, a petrol-drinking sex worker).

These two aspects of his writing—a pamphleteering interest in big-picture politics and a desire to push the boundaries of the novel form—are not easily or usefully separated. On the contrary, it is Bhattacharya’s political commitments, above all his desire to expose the logic of neoliberalism, that drove him to dream up new, abrasive kinds of storytelling. He wanted to capture the corrosiveness and sheer vertiginous speed with which capital—suddenly and abstractedly injected into a system—upturned the entire social order, deforming human relations.

This is already evident in Harbart, Bhattacharya’s first and most famous novel, which has now been published in a new English translation by the editor Sunandini Banerjee. Originally brought out by a small press in Calcutta in 1994, right after the economic reforms, this scabrous book, long a cult favorite in India, might be classified as “free-market parable.” It is named after a principle character, the bachelor Harbart Sarkar, but the novel’s true protagonist is in fact the business Harbart founds, or stumbles into founding. In its short, turbulent life, the enterprise—a sham, but so what?—drives the story forward, corrals the supporting cast, and leads its proprietor to his sad downfall.

Harbart himself is an exceedingly strange creation. Like some of César Aira’s heroes, he is less a rounded psychological being than a walking enigma, briskly drawn and liable to dissolve under close scrutiny, but perversely compelling for all that. Bhattacharya fills in his backstory in the opening section: as in a fable, Harbart is the prodigal orphan raised in his evil uncle’s fancy Calcutta home, largely unloved and totally unattended. He drops out of school in grade six (no one notices), after which he basically lives in his own head. Miraculously, he makes it to middle age having changed little, a near-illiterate scrounger arrested in dreamy preadolescence.

It is hard to imagine a less suitable entrepreneur. In another novel, Harbart might have been a holy fool. How appropriate then that he is turned into a kind of god-man, a figure who combines the wiles of the former with the latter’s aura of piety. (Such frauds remain popular in India.) A series of comic misunderstandings convince Harbart’s neighbors that he is a spirit medium, and on this reputation he establishes a small business out of his bedroom, named “Conversations with the Dead.”

This fit of sudden opportunism opens the novel out onto the social world of Calcutta. In a few tart episodes we follow Habart’s one-man start-up as it grows into a minor sensation, drawing in the bereaved, the confused, and the simply idle, rewarding them with the only real spiritual satisfaction available under capitalism, a solid discount (Harbart is cheap by god-man standards). His fame eventually tickles the interest of rapacious investor Surapati Marik—owner of “property, fish farms, coal mines, mopeds”—a true representative of the new gilded India.

Marik offers to take Harbart’s occult business big time, into the realm of global elites, who also sometimes need help from the dead. Here is the sales pitch, delivered in his pungent business-patois:

Five hundred rupees a visit. Minimum. Much more for special cases . . . What message a dead politician is sending—to reach it just once into the ears of a live politician. And thus to capture a few king-pins and big-bulls. Alongside, detachment, indifference. Then Dubai. Bahrain. Dead sheikhs, live sheikhs . . . RSVP. RIP . . . Oh I can’t go on. Hang on, let me pour another. This stuff’s smooth—no?

Harbart signs the deal, a fatal decision that will lead via a carnival of destruction to his own demise. Admirably, this is not presented as a personal tragedy, though it’s kind of sad, let alone a moral lesson about greed, but as a literal illustration of how the free market consumes human life. It is an unflinching conclusion about the present state of affairs, one which few liberals could sympathize with, or even comprehend, as it destroys the very model of homo economicus to which they are committed.

Is Harbart a “great” novel? Probably not. It lacks something of the essential mystery and human scope we associate with Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy or Knut Hamsun’s Hunger. Is it an important novel? Absolutely. As societies crumble under the assault of finance capital, and as the rhythm and long arc of human life are disfigured beyond recognition, old forms of novel-writing, especially realism tethered to an individual narrative, are fast turning irrelevant, even reactionary. What is needed instead is a kind of novel that attends to how society is being organized by certain vested interests; a novel that goes to the heart—rather, goes for the jugular—of the economic system itself. Harbart is prophetic of this tradition to come.

Ratik Asokan is a writer and editor. Originally from Mumbai, India, he presently lives in New York. His writing has appeared in The Caravan, the Times Literary Supplement, The Nation, and the New York Review of Books Daily, among other publications. Between 2017 and 2018, he worked as an assistant editor at Art in America.