Blake Gopnik

Blake Gopnik

The artist receives a massive doubleheader of a retrospective.

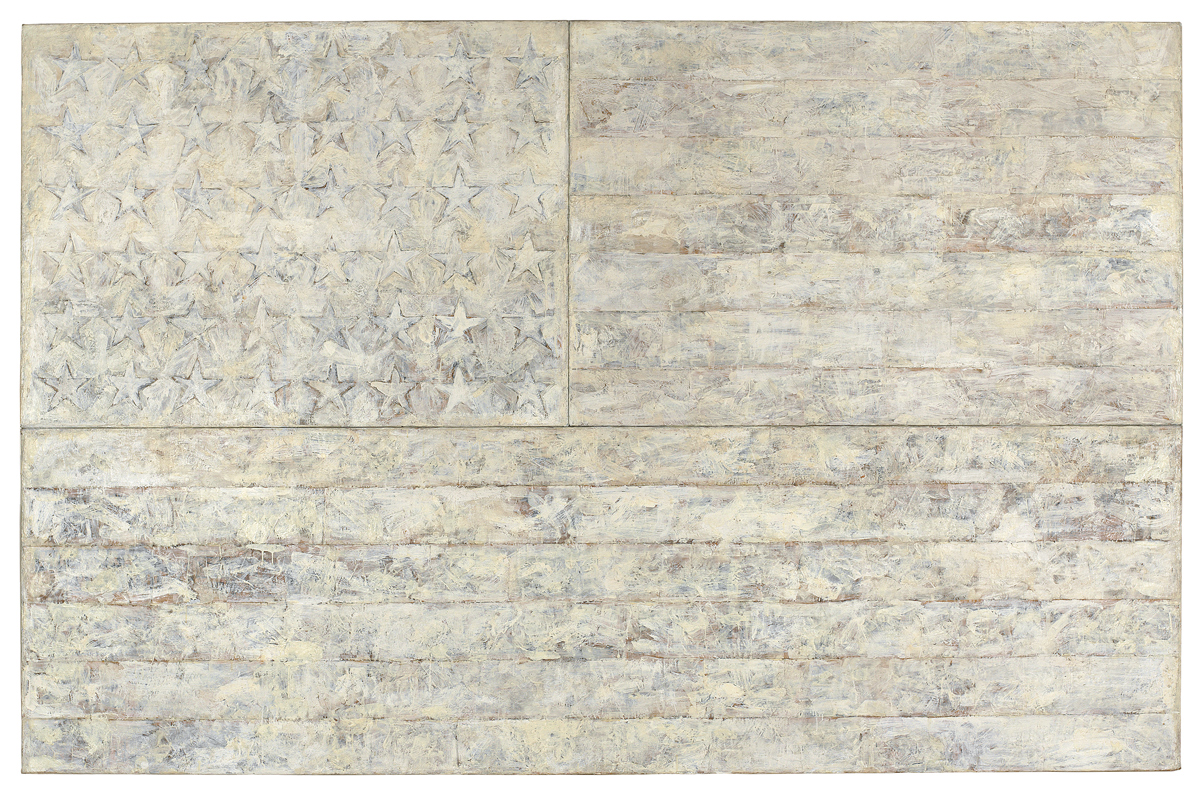

Jasper Johns, White Flag, 1955. Encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric (3 panels), 78 1/4 × 120 3/4 inches. © 2021 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS). Photo: Jamie Stukenberg.

Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, curated by Carlos Basualdo and Scott Rothkopf with Sarah B. Vogelman and Lauren Young, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Pkwy, Philadelphia, and Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through February 13, 2022

• • •

In January of 1956, Bonwit Teller, a high-end department store on Fifth Avenue in New York, placed a fancy scroll at the front of one of its window displays. In genteel cursive, it read: “Young American Clothes by Lanz . . . Young Seventh Floor.” And sure enough, behind that scroll stood two mannequins done up in lovely pale dresses, just right to clothe youth for the coming spring season.

A second, more unexpected scroll, placed right beside the one selling Lanz, read: “A painting by Jasper Johns, one of the young American artists who has worked with us on window displays.” And there indeed, hanging behind the mannequins in their “young” clothes, stood that painting, equally fresh and similarly pale: it was Johns’s great, vast, landmark White Flag—the first major Johns seen anywhere, getting its premiere in a store window.

There’s a special tension between the eccentric, avant-garde greatness of that early Johns—its virtues register even in the lone photo that survives of the window—and the fact that the painting, and thus the entire Johns “project” that got launched with his flags, was first revealed in a vitrine meant to move merchandise. I think this tension is palpable, as a driving force, across all of Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, the stunning two-venue retrospective that just opened at the Whitney Museum in New York and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. With more than five hundred works on view, it is very probably the most expansive, extensive, impressive exhibition ever dedicated to a living artist. It covers the tremendous range of Johns’s signature subjects and styles and series—flags and targets, numbers and letters, beer cans and flashlights, cross hatchings and hands, catenaries and skulls—in the countless media and techniques that he’s used over the seven decades of his career. At ninety-one, Johns has even made new work for this latest show, sixty-five years after he made his first splash at Bonwit’s. But despite his retrospective’s vast scope in time and its overwhelming scale—or maybe because of both—I left with a clearer view of Johns than I’d ever managed.

Having the full span of his work on view, and in mind, helped me bring it all into focus through the glass of that Bonwit’s window.

Jasper Johns, Painted Bronze, 1960 (cast and painted in 1964). Bronze and oil paint (3 parts), 5 1/2 × 8 × 4 5/8 inches. © 2021 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society.

I think the department-store setting posed a problem for Johns that lurks behind almost everything in his huge show. By the time of his Bonwit’s appearance, the modernist vanguard had spent at least half a century decrying any work that served as a “mere” commodity, despite the evident fact that most art was intended to sell, or aspired to sales even when it seemed unsaleable. The Bonwit’s window made that fact unavoidable, thanks to its pairing of those Lanz dresses with the supposedly radical, and no doubt unsaleable, White Flag. Was the flag supposed to help move the dresses? Were the dresses meant to help the flag seem buyable? Either way the linkage between art and sales had been made patent and could not be wished away.

Once upon a time, artists and critics might have had a way out of this dilemma. They could claim that however commodity-like a painting might seem, as an object, it was in fact pointing away from its place down on earth—even in a shop window or sales gallery—to other, higher realms of thought and spirit. By the 1950s, however, John Dewey’s reigning Pragmatism, as it came to be applied to art by acolytes such as the collector and pedagogue Albert Barnes, had had decades to close off that option. For Dewey and Barnes, art simply had to be thought of, contemplated, and enjoyed in the same terms, and at the same time, as all the other objects in the world that help build our lived experience as human beings.

As Johns once said, in a moment of pure aesthetic Pragmatism, “A picture ought to be looked at the same way you look at a radiator.” (Barnes did not collect radiators, but he did buy old keys and hinges to hang with his paintings.)

This led to the dilemma that shaped Johns’s project for decades to come: how to insist on the absolute objecthood of a work—its resolute, Deweyan here-and-now-ness—without letting it settle into the unlife of a mere product on display. (That was an accusation leveled against Abstract Expressionism just as Johns came of age as an artist, by foes who compared AbEx to wallpaper and tie fabric; Johns’s moment at Bonwit’s was also the moment when AbEx was actually beginning to sell.)

Jasper Johns, Map, 1961. Oil on canvas, 78 × 123 1/4 inches. © 2021 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS).

White Flag itself, now hanging on the un-retail walls of the Whitney, offers clues to some ways out that Johns found. Seeing the painting in the flesh, you realize that the single American flag that is its sole subject, filling the frame edge-to-edge, is actually painted across three separate canvases assembled into a single field; that doesn’t decrease the palpable materiality of Johns’s object, but it does fracture it to become something like a factory “second” that is not quite sales-ready. Fracturing, and the failure to function it implies, becomes a hallmark of just about every work that comes after White Flag in the Johns retrospective: maps are so thickly painted that you can’t read the names of their states; a text painting that is all about color has a blotch of orange that is mislabeled “RED” in letters stenciled upside-down in blue; the numbers zero to nine, which ought to be the ultimate symbol of order—and of orderly sales, for that matter—get worked and reworked to the point where they cannot be counted.

Jasper Johns, False Start, 1959. Oil on canvas, 67 1/2 × 53 1/8 inches. © Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Meanwhile, the very flag-ness of the Bonwit’s painting—the fact that it is, famously, both an almost-functional United States flag and a painted representation of Old Glory—lets it live in the world of material objects (and goods) while also leaving mere objecthood behind to point to a whole field of political and cultural meanings. Those exist quite outside and beyond the work’s material (and retail) presence and save it from mere commodification, while also depending completely on what it is as a thing. A flag—any and every flag—may be an object and thus potentially for sale, but in essence it is always at the same time, and equally, an idea. Johns, godfather of ’60s Conceptualism, uses objects to signpost a world of pure thought that has the particular virtue of being beyond price. (When Johns sold out his first solo show, held two years after his Bonwit’s debut, the one painting he chose to keep was White Flag. I imagine that it stood as a talisman.)

The current retrospective is described, in its catalog, as “an orchestrated constellation of perspectives on Johns’s work,” and it is indeed built around some dozen themes and leitmotifs—“display,” “place,” and “reveries,” for instance. But “doubling” is the theme that really rules the day. Hence the “mirror” in the show’s title and the survey’s reflection across two venues, where curators Scott Rothkopf of the Whitney and Carlos Basualdo of the PMA, working semi-autonomously, have prepared checklists and installations that are quite different and yet manage to portray much the same Jasper Johns.

Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, installation view at Whitney Museum of American Art. © Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS). Photo: Matthew Carasella.

And I think all these twinnings have their roots in the ur- and indissoluble pairing, in Johns, of the material and the immaterial, the consumable and the evanescent, the object and the idea. It’s there even in the art supplies he used for White Flag and for so many of his other early works. The entire surface gets covered in a thick, fractured, visibly incarnate scumble of pigmented wax—the “encaustic” known since antiquity, and surviving since antiquity, as one of the most durable of paints. And then all that permanence gets applied over a layer of torn newspaper scraps that work as a perfect marker of ephemerality and the not-worth-saving. As future fish-wrap, newsprint also rejects art’s status as a fine object, worthy of Lanz-clad girls with martinis, and brings it instead into the realm of words and thoughts.

Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, installation view at Philadelphia Museum of Art. Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo: Joseph Hu.

Or sometimes Johns starts out with motifs from that world of pure idea, as in the letter and number paintings he began in the ’50s, and then takes care to give them a notable material heft, rendering them in the thickest of wax or even in a metal paste. Sometimes he cuts his numerals and ABCs out of wood, to fully object-ify them; he always uses fonts and techniques from the sign painter’s tool kit, grounding the abstractions of counting and spelling in the quotidian, commercial world where numbers and letters get used.

Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, installation view at Whitney Museum of American Art. © Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS). Photo: Matthew Carasella.

That particular duality is at the heart of the many other kinds of doubling in Johns. On the one hand, showing an object more than once in your art, or producing two copies of the same piece, as he does, gives a sense that you’re more interested in the abstract idea behind the material thing than in any one instance of it; you can imagine copies of it tessellating out forever, in every direction, as nothing more than varying pointers to its Platonic form. On the other hand, repetition, in the context of postwar America, is always also about mass consumption—it’s that Lanz dress, made available to any girl who wants one. (Bonwit’s once used its store window to stage a competition between two identical dresses: a one-off, $788 couture frock from France and its factory-made American copy, every bit as good for $45. Johns’s paintings and prints appear to model a similar contest between modes of production, even as they fill a commercial need to supply goods at different price points.)

Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, installation view at Philadelphia Museum of Art. Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo: Joseph Hu.

But that brings us to the problem with the Johns retrospective, one that can make it feel almost tragic. For the first ten or fifteen years of his career, the dilemmas fueled by his Bonwit’s moment—by that postwar moment in American life and culture—have an amazing energy, producing ever-new works that manage to transcend their status as mere objects for sale. (Which they clearly were, all along.) At a certain point, however, even though Johns continues to make impressive moves in his project, it has gelled into such a new normal for art that his works have a hard time evading their freshly achieved artiness. Rather than seeming to resolve or even explore how an object can sidestep its commodification, Johns is stuck, whatever he does, being a maker of trademark objects signed Johns—stuck with being the art world’s own “Lanz.”

Jasper Johns, Untitled, 1998. Encaustic on canvas with objects, 44 1/8 × 22 1/2 inches. © 2021 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society. Photo: Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics.

After coming to the end—twice—of his doubled retrospective, it felt to me as though Johns could not move onto fresh terrain because he was marooned on the new continent that he’d built. He’d have to leave it to other artists—Andy Warhol, David Hammons, Barbara Kruger—to take off from there and explore what lay beyond.

And then I had a sudden and surprising revelation: although, as a critic, I spend too much time with art to want to buy and own more of the same, for once I had found myself jonesing—or Johnsing—for any number of works on display. I’d been billing Johns as the thinking-man’s painter, but here he was making stuff that just begged to be hunted and gathered. Could that mean that a shop window is a right and fine place for art, after all, however much art might try to escape it?

Blake Gopnik has been the lead art critic at the Globe and Mail and Washington Post and is a regular contributor to the New York Times. Warhol, his comprehensive biography of the Pop artist, was published in 2020.