David O’Neill

David O’Neill

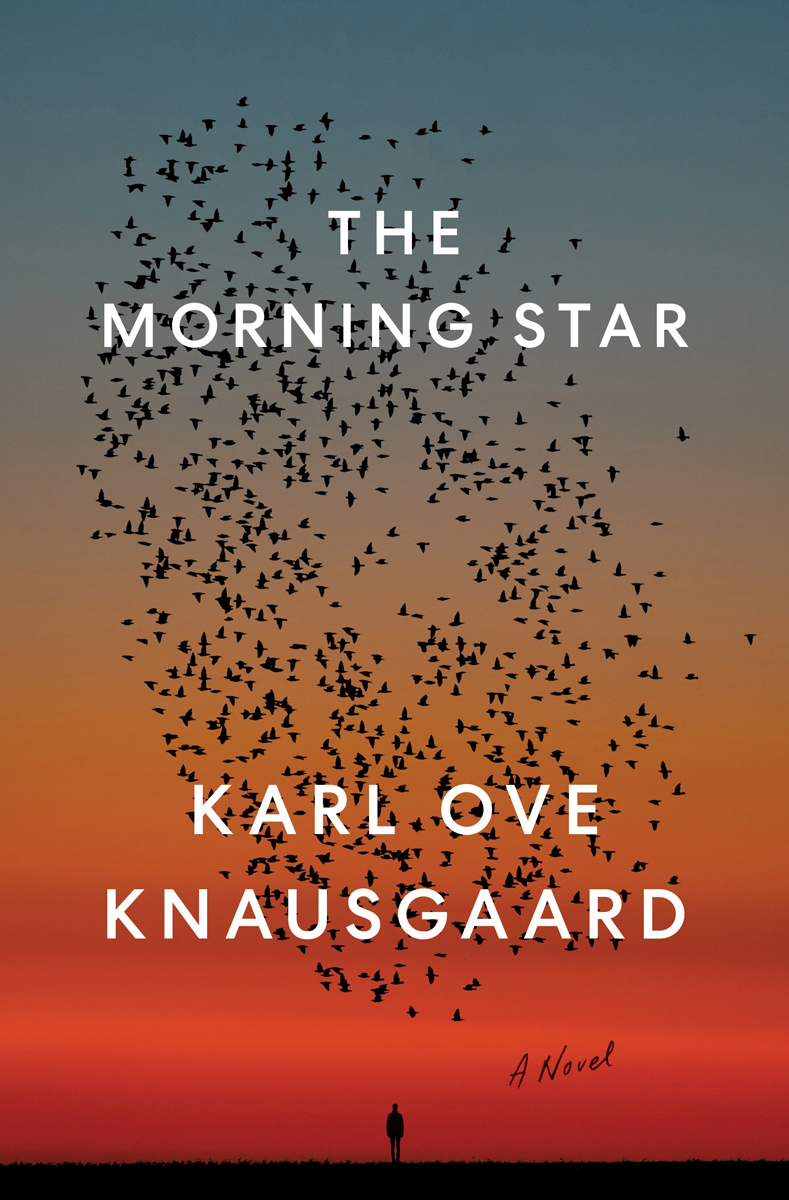

Caws and cliffhangers: Karl Ove Knausgaard attempts genre fiction.

The Morning Star, by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated by Martin Aitken, Penguin, 666 pages, $30

• • •

The disquiet starts early in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s new thriller, The Morning Star. A dead kitten, crabs littering the road, weird birds. And then there’s that star of the title, an unexplained celestial phenomenon both amazing and foreboding: “A light rose into the sky. It wasn’t the sun. It wasn’t the moon. It was a kind of star. But how big it was!” Christianity tells us the morning star is Lucifer—“you who have weakened the nations”—but also Jesus. In the novel, it’s a harbinger of evil, from ritualistic murder to a son coveting his father’s wife. For a moment, at least, it stops all of the book’s nine main characters in their tracks. Then they get on with their lives, which the book presents in a round-robin of first-person narration, one chapter per speaker. Perhaps gunning for HBO Max, Knausgaard ends most episodes with a cliffhanger: a phone lighting up ominously in the seat of a car, a priest noticing that the dead body at a funeral she’s presiding over is a man she had just seen in an elevator.

It couldn’t be, though, because this funeral was booked a week ago. . .

The Morning Star is Knausgaard’s first new novel since his 3,600-page autofiction blockbuster My Struggle, a series of six books that casts a long shadow over these pages. The fun of My Struggle wasn’t just Knausgaard’s oversharing, his penchant for self-immolation on the page, or the artless chatter of his prose antistyle. It was that it felt new but was actually a throwback, offering readers the chance to believe again in literature’s old promise, that writers’ lonely struggles are heroic and that an individual’s consciousness can be atomized on the page to everyone’s great profit. The Morning Star aims for something different—the frolic and abandon of genre fiction—but it still reads like an allegorical enactment of My Struggle’s ruminations, which punctuated the narrator’s everyday existence: the death of his father, scoring beer as a teenager, the humiliations of being a man running errands, writers’ retreats, grooving to Gen-X records. For fans of the struggle, The Morning Star might be disappointing. It’s more pleasurable to watch a guy philosophically daydream while he’s buying tinned fish than it is to watch that daydream play out as fiction.

The characters of The Morning Star also have a dour sameness about them, and the plot, divided among them, is choppy. We get Arne, an unhappily married professor who kills the kitten with a hammer after his manic artist wife beheads it; Emil, a daycare worker who drops a child but doesn’t tell anyone; Iselin, a young musician who sees a fire no one else can see; Kathrine, the priest, also unhappily married, who gets accused of heresy after that eerie funeral; Vibeke, a young mother happily married to a much older man; Solveig, a doctor who witnesses a dead man come to life while she’s helping to harvest his organs; Jostein, a know-it-all journalist who couldn’t be more pleased about a scoop involving a ritual murder; and Jostein’s wife, Turid, a nurse who endeavors to rescue a runaway patient named Kenneth in the Norwegian woods. This last scenario has the feeling of a parable, but it soon becomes a B movie. Turid finds Kenneth and watches a strange figure approach him. It’s a man with an ox-like head who moves with surprising fluidity. He’s carrying a vessel in one of his oversized hands:

The man dipped his hand into the vessel and placed it on Kenneth’s brow. A shudder went through Kenneth’s body and he fell backward onto the ground.

The man turned and looked at me.

His eyes were yellow, only it wasn’t a man. It wasn’t a man.

Then there’s Egil, Arne’s buddy, who is the book’s most emblematic character and who writes its last chapter. (“Writes,” not “narrates,” because the novel’s closing words are an essay, “On Death and the Dead,” that’s a dramatic break from the story.) The day after the morning star shows up, Egil considers its appearance in the Bible. He visits a church and opines that biblical motifs were “like a fairy tale,” then asks God for a sign anyway. He sees a raven that caws three times:

Bewildered, I began to walk again. I had asked for a sign, and a bird had come. It was a coincidence, it had to be! If there was a God, an almighty, he surely wouldn’t care what I did or said!

And yet: a bird had come. It had looked straight at me. And it had cried three times. Not two, not four.

After I’d been pondering the fairy-tale aspect of Jesus spending three days in the kingdom of the dead.

Egil, like the narrator of My Struggle, dares himself to feel something like faith. Knausgaard’s autofiction eloquently dramatized the battle of its own making, so it’s hard not to envision the author composing a passage like this. His search for meaning has always been intricate, learned, frustrated, and frustrating. Egil’s concluding essay makes this search explicit, recasting the book’s fantasy elements through familiar Knausgaardian themes, like how allegorical, philosophical, and artistic reckonings with death always abstract it, making it unrecognizable when it really arrives. At first, the effect seems similar to the one created by My Struggle’s essay about death in volume one. But in The Morning Star, the frame shifts as Knausgaard’s nonfiction voice slips away and Egil recounts an episode straight out of a Stephen King novel (it’s very close to the premise of King’s recent pulp fiction Later). Here, King-style horror/fantasy is used to make death feel more real.

I read this authorial sleight of hand, and Knausgaard’s use of nine first-person narrators, as a sign that he distrusts or resents his own unadorned voice, the one that enchanted millions of readers simply by reciting the mundane details of life. His autofiction played with that power of enchantment, impeding narrative immersion by changing modes of address (from fiction to essay and back again), frequent flashbacks, and constantly calling attention to the act of writing. Genre fiction has a larger field of play, but Knausgaard doesn’t trust that either. He won’t let us totally believe in the world he’s made and won’t—or can’t—end on a high note like King always does. And while Knausgaard speaks through different characters, readers will notice some very Karl Ove–sounding lines and preoccupations no matter who is addressing the audience. “When death comes,” Egil writes, “and someone we are close to is plunged into its darkness, the net, spun only from thought, comes apart and we despair without hope, racked with pain and grief, until it passes and the abyss is covered over once more.” The bard of bad vibes would like to remind you of some home truths.

David O’Neill is an editor, writer, and teacher in New York. He co-edited Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz.