Ed Halter

Ed Halter

A photography show captures the gay-cruising world of Manhattan’s

West Side piers.

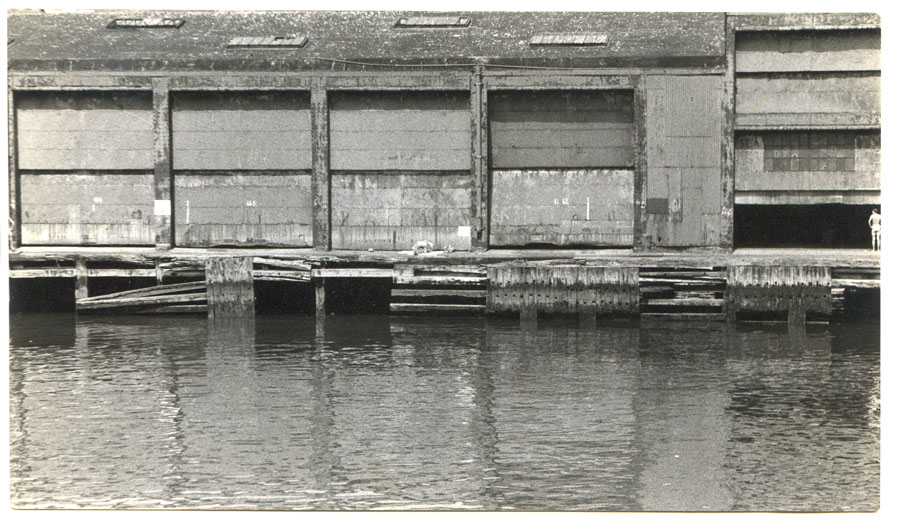

Alvin Baltrop, The Piers (collapsed), n.d. (1975–86). Gelatin silver print, 4.5 × 6.7 inches. Image courtesy Bronx Museum of the Arts.

The Life and Times of Alvin Baltrop, Bronx Museum of the Arts, 1040 Grand Concourse, Bronx, New York, through February 9, 2020

• • •

A little over a decade since Alvin Baltrop achieved posthumous renown for his astonishing photos of Manhattan’s West Side piers, taken in the ’70s and ’80s when the structures had become a now-legendary gay cruising site, the artist’s natal borough is hosting the largest survey of his original prints at the Bronx Museum of the Arts. Baltrop had been long neglected by museums and galleries until historian Douglas Crimp published a belated encomium, four years after the photographer’s death, in a 2008 issue of Artforum. Subsequently, Baltrop’s work became central to an ongoing fascination with the crumbling, abandoned structures—particularly Pier 52, formerly located at the end of Gansevoort Street—as important spaces of artistic and subcultural activity in drop-dead New York. The long streak of scholarship and exhibitions addressing the piers stretches from the Reina Sofia’s Mixed Use, Manhattan, curated by Crimp and Lynne Cooke in 2010, to the 2019 publication of scholar Jonathan Weinberg’s comprehensive study Pier Groups: Art and Sex Along the New York Waterfront. The piers have by now displaced less egalitarian locations like Studio 54 or Max’s Kansas City as the preferred gathering place for collective memories of the period.

Alvin Baltrop, The Piers, “Pick Pocket watch for your wallet – Paradise,” n.d. (1975–86). Gelatin silver print, 4.5 × 6.7 inches.

This focus on the history of the piers has allowed for the reassessment of diverse creative practices in relation to a time and place when the full expression of queer life in New York could not be extricated from the precarious realities of the city’s underclass—activities ranging from the performances of Joan Jonas and Vito Acconci, to the literature of David Wojnarowicz, to the architectural interventions of Gordon Matta-Clark (whose 1975 Day’s End, a cut piece sawed into the side of Pier 52, is documented in several of Baltrop’s pictures). The value of Baltrop’s photography in this new understanding of New York’s queer past is twofold. It lies not only in the visual preservation of the piers and the at times seedy activities that transpired there, but also in the poignant biographical details of the artist himself. Baltrop, a black, bisexual working-class man who chronicled the piers as part of a grand, all-consuming project stretching over years, received only a few minor accolades and virtually no financial remuneration for his art during his lifetime, dying of cancer at age fifty-five after decades of working numerous low-wage jobs.

The Life and Times of Alvin Baltrop, installation view. Photo: Argenis Apolinario Photography.

The Bronx Museum has staged the exhibition in a single large room, with each of its four walls covered in long loose grids of framed prints in varied but modest dimensions, many only snapshot-sized, and a vitrine containing a selection of the artist’s personal effects, including his cameras. One of the walls bears examples of Baltrop’s earliest photos, made between 1968 and 1973 and most while serving as a navy medic; the other three are devoted to work shot between 1973 and 1986, primarily at or around the piers. Since Baltrop did not title or date his work, such information is not provided here for individual images, granting a blanket anonymity to the men he captured, diminishing distinctions between friends, lovers, and strangers.

Alvin Baltrop, Untitled (Navy), n.d. (1969–72). Gelatin silver print, 4.5 × 6.7 inches. Image courtesy Bronx Museum of the Arts.

Baltrop’s navy years took place aboard the USS William K. Pratt, a destroyer that patrolled the Atlantic during the height of the Vietnam War. There he spent his downtime practicing and perfecting his photography, using his shipmates as subjects, developing images in medical trays, even building his own enlarger. He had begun learning to use a camera as a teenager, snapping subjects like patrons at the Stonewall Inn and Malcolm X speaking to crowds, though Baltrop’s Jehovah’s Witness mother burned the results of his juvenile efforts upon discovery. A number of his pictures taken aboard the Pratt show his fellow sailors at leisure, sunning themselves deckside wearing little more than navy-issue briefs, in casually voyeuristic images that foreshadow the naked urban sunbathers who lounge around in his later work. Others are more explicit erotic studies, experimenting with cinematic lighting to reshape young bodies into glowing forms.

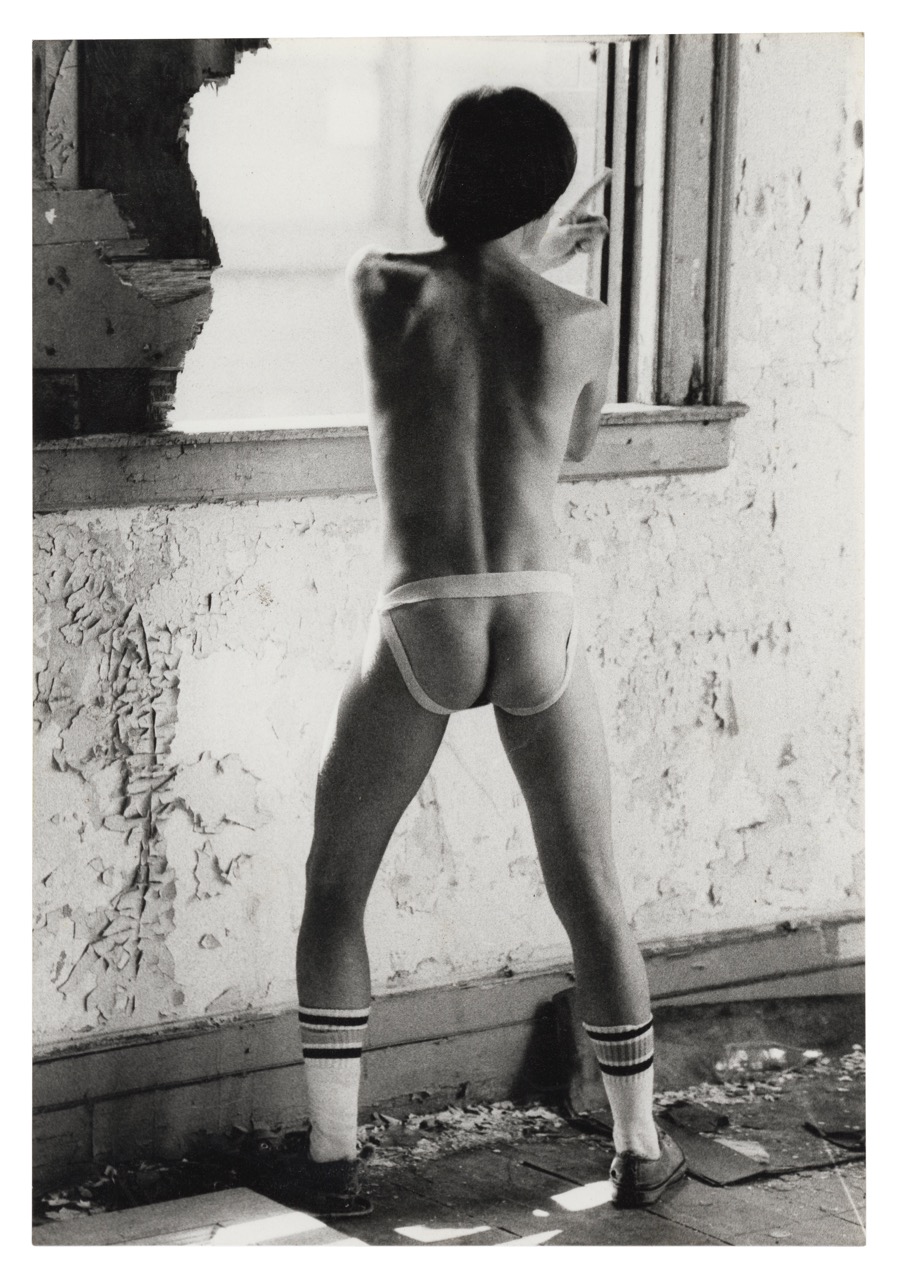

Alvin Baltrop, The Piers (man wearing jockstrap), n.d. (1975–86). Gelatin silver print, 6.7 × 4.6 inches.

Following an honorable discharge, Baltrop returned to New York, eventually enrolling at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan and working as a taxi driver. It was during this time, in his mid-twenties, that he first discovered the piers and began taking photographs there, drawn to documenting the sexual adventurers, homeless people, young runaways, and miscellaneous criminals who populated those ruins. He would park by the piers’ edge and live out of his van for days at a time, returning to eat and sleep in between long forays of picture-taking and other pleasures. To achieve some shots, he suspended himself in a homemade harness from ceilings inside the piers’ buildings, waiting with the patience of a wildlife photographer for some activity to transpire below.

Alvin Baltrop, The Piers (couple having sex and two other people standing on the dock), n.d. (1975–86). Gelatin silver print, 4.5 × 7.75 inches.

Though not to the extreme of Baltrop peering from the rafters, viewers too must spend time scanning these dense stretches of shadowy tangled wreckage and sunbaked industrial facade before espying some tiny human figure hidden in their architecture. This delicate compositional effect is reminiscent of the incidental subjects of a Bruegel painting, but we’re also invited to a more phenomenological understanding. Baltrop’s most visually complex photos give the viewer a sense of the raptorial optics inherent in the act of cruising, compelling the viewer to hunt in the darkness with him. Other photos fulfill cruising’s desire for connection with intimate images of public sex in action, lithe young men roaming the wreckage in various states of nudity. Some seem captured in the act, others clearly pose for the camera. Portraits of individuals are generally close-up and eye to eye: in Baltrop’s photo of Marsha P. Johnson, the activist gazes warmly back into the lens, her face and hair filling much of the frame.

Alvin Baltrop, Marsha P. Johnson, n.d. (1975–86). Gelatin silver print, 8.6 × 13 inches.

Among its selection of over 225 photographs, the exhibition includes a few images that appear in multiple versions, at times hanging side by side, displaying differences in cropping and sizing. This curatorial tactic was also employed by Douglas Crimp in a 2017 Baltrop exhibition he curated at Galerie Buchholz in New York, and as in Crimp’s show, many of the photographs here appear damaged, scarred by creases, torn at the edges, splattered with stains. Such material indignities serve as metaphors for the rejection Baltrop received from the art world when he was alive: showing his portfolio to one gallerist, she dismissed him as “a real sewer rat type of person,” while others refused to believe that Baltrop could have taken the pictures himself. One gatekeeper even accused him of stealing his portfolio from a white photographer and passing it off as his own.

Alvin Baltrop, The Piers (exterior), n.d. (1975–86). Gelatin silver print, 6.5 × 4.5 inches.

The historical lack of care evidenced in these materials provides its own important testimony. The Bronx Museum’s show arrives on the heels of major Manhattan retrospectives of Peter Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe, two white gay photographers of the period who more or less successfully trafficked in images taken from their own downtown bohemian lives, leaving behind photos whose pristine condition tells a very different story, of their moneyed trusteeship over time. Baltrop’s corpus, in contrast, reminds us what the remnants of a more inescapably and unprofitably marginal life might look like.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His collection From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Review Film Reader, coedited with Barney Rosset, was published in 2018 by Seven Stories Press.