Lauren Berlant

Lauren Berlant

Anne Boyer’s cancer memoir insists on the commons of suffering.

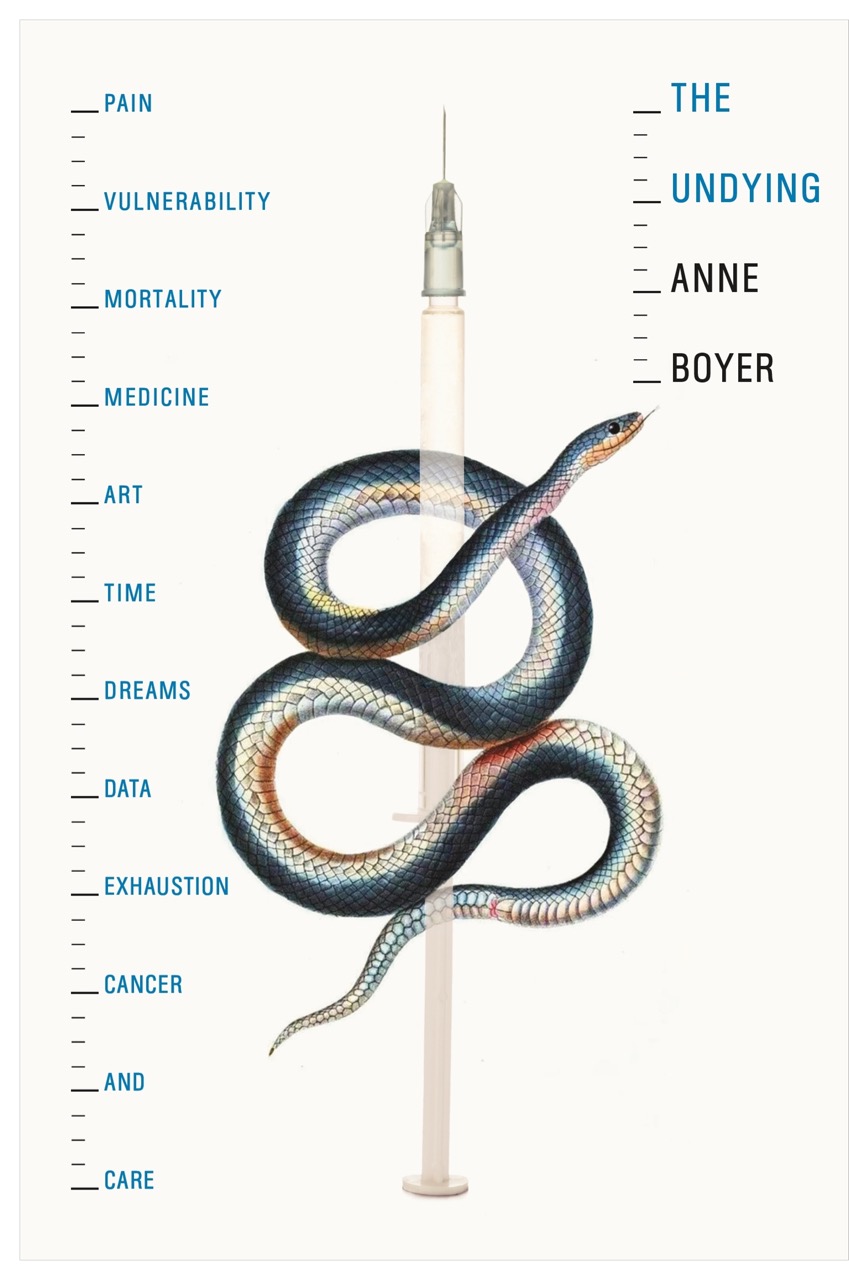

The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care, by Anne Boyer, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 308 pages, $26

• • •

“Breast cancer is a disease that presents itself as a disordering question of form,” writes poet and essayist Anne Boyer. Form of what? Of testimony? Of exposure? Of vulnerability? Of injury? Of care? Of identity? Of time? Yes yes yes: no genres of life and art are spared by cancer or this book. All appear in The Undying as disordered forms, gestures of partial efficacy disturbed by chronic illness. Neither a form of life, exactly, nor a form of death, the breast cancer this book makes visceral takes on the shape of something lenticular, smudged like the present that’s defined by crises that are the effects of so many causes. The Undying multiplies the befores, durings, and afters of active-duty precarity.

The Undying is like a “make your own adventure” book, but Boyer, now in remission, plays it out first, to help you in case you too face your mortality but get a second chance. It flails for genre, because she flailed for a genre throughout to stabilize the event. The book is present to Boyer’s experience of every moment she could capture, but this very aesthetic presence means that the illness narrative’s usual arc of moving from cluelessness to suffering and then transcendence, death, or self-acceptance is replaced here by a series of intense, cumulative, social, and lonely episodes that are both physical and affective.

The Undying wants to be about everything, somewhat like Paul Preciado’s Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. Life is caught up in the contemporary system of medico-pharmacological ideology, neoliberalism, political economy, the carcino-desperation complex, the couple form, friendship, social and sexual reproduction, the illness archive, the intimacy archive, the political economy of diffuse and material modes of care, loneliness, philosophy, tone of voice, tone of life, the systemic, the singular, the ladder between the case and the universe, the aspirational human caught in a circuit of trying, the exceptional and the ordinary, the mechanical and the metaphysical, torture as cure, the democracy of exhaustion and depletion that is terrible but doesn’t defeat the author’s attachment to life, knowledge, or writing. I gathered these tropes from the places in The Undying where I wrote “key” in the margins.

In Preciado, attachments to lovers and the analyses of structural determination and class projects like neoliberalism are pretty separated out narratively and rhetorically, so the joy-critique toggle takes on distinct tones. In Boyer’s The Undying, in contrast, everything converges. Love, motherhood, doing dishes, poetry, being known, being read, getting into and out of cars, shopping for clothes, fighting physicians, getting irritated and sentimental and so on—they’re all enmeshed. She says she wants to document her ordinary. She wants to use ordinary language to do it. She looks for precedents in the illness archive of Aristides, Susan Sontag, Audre Lorde, “Coopdizzle,” Fanny Burney, John Donne, and Kathy Acker—texts that took seriously the sense of suffering as an event of the body breaking in a specific social scene. With them, Boyer develops a free-floating stubbornness, committed to the life she had cultivated, condensed in the capacity to write figuratively and therefore to create worlds beyond what’s in front of her.

Meanwhile, though—the book mainly documents the meanwhile—we learn that she taught full time during her treatment, but little of that experience makes it into the book’s insistent internal monologue. What does appear is astonishing, there’s just not much of it:

I’m angry that days after surgery I have little choice but to be driven to work by my friends, all of whom have already had to make great sacrifices to help me, who must carry my books into the classroom for me because I can’t use my arms. Delirious from pain and loss in those days after my surgery, I give a three-hour lecture on Walt Whitman’s poem “The Sleepers”—“wandering and confused, lost to myself, ill-assorted, contradictory”—with surgical drainage bags stitched to my tightly compressed chest . . .

But she has been told to closet her suffering at work, not to show her weakness, to be a model of bravery. If aversion to TMI was the rule in vicious bureaucracies and caustic health economies, Boyer reverses and revenges here.

What happens when you live at the limit but don’t die? In The Undying, “living takes the shape of the effort to exist. In the long night of this effort to exist’s case file, each hour recedes into a lack of energy to achieve a measure of that hour’s length. Everything is tried—that’s how it gets exhausted—and a person trying to take notes on this writes, ‘I’m exhausted,’ because they are too tired to put down their pen.”

Boyer thinks of exhaustion as a universal experience of the contemporary—not just the sick, but the proletarianized, which includes an increasing mass of persons. The book knows not all exploitation and exposure are the same, but it also insists on the commons of suffering. People will have conflicting, maybe roiling, responses to its various claims that cancer is the world’s fault, that cancer is democratic, that cancer is the poor person’s disease, and that of the unlucky ones, and exemplary here, and singular there.

So, if there’s no redemption narrative and barely a resilience one, there’s a rolling sense of forsakenness, gratitude, defeat, love, and rage. There are lawyers, insurance companies, bosses. Although Boyer has lots of friends, and a child, she feels “alone” because no partner’s there, which is lamented. She loses people and fingernails.

Boyer thus calls the crisis of cancer a crisis of redaction: What does cancer subtract from a person, from the world in which it is pervasive, from life? Is it possible to have something other than a mimetic relation to it, to refuse to be subtracted, to use writing as a conversion machine for silences until—she cites Lorde—they have “the sounds of brightest day and loudest thunder”? The Undying is another document testifying to the collapse of possession and dispossession, as the disease and the pain of cure take her from and shove her into, and beyond, herself.

It is often said, after Wittgenstein, that pain induces a secret life. Boyer doesn’t buy it. On the one hand, “every person with a body is a secret historian,” but pain has a big archive and she charts that, down to the absurd 1-to-10 pain rating that the experts force on bewildered patients. She does not see the experience of intense pain as a singularity someone is stuck in forever, a spinning homunculus in a personal hell. Her version of pain is that it’s in the world and makes a world. There’s unbelievably bad physical pain; there’s the whining of the soul for not having ready-to-hand magic carpets to float on like partners or good insurance or time to recover, really recover; there are the insane insults of intimacy with friends who disappear, and side effects that screw you to the ground once or forever, changing how the past matters, overtaking identity as traumas will.

I think any reader, but certainly I, would also feel lost in the middle of so many middles that compose Boyer’s book. I was muddled, but I coasted, then on multiple readings took in multiple cliffhangers, falls, rages, and arcs of stated and implied desire. That was more than okay. Spend time in the room with this. It may not want to be the book that you send to the diagnosed or dying, but to survivors who don’t feel miraculous. After all, if the poetry of illness is a poetry of remains, the “remain” is not something that exists only after death, but also after whatever form of life is abandoned, so that the stuff that had propped it up suddenly looks like it has failed even to achieve landfill, becoming the junk of junk.

Boyer is trying to pick up the junk on the side of the road that might help a future person who doesn’t die from her potentially terminal illness to have something to restart with. So that a future drowning subject has a flotation device that serves as a reality check. All illness memoirs are conversion narratives in that sense, showing how some captive person became another kind of being. Maybe, in the solitary confinement of survival in the world that is also crowded, the story of her adaptation can be converted into a resource for yours.

Lauren Berlant is George M. Pullman Distinguished Service Professor of English at the University of Chicago. She is the author of Cruel Optimism and The Female Complaint, and most recently, coauthor of The Hundreds with Kathleen Stewart.