Ed Halter

Ed Halter

A reverence runs through it: Catholicism in Warhol’s art.

Andy Warhol: Revelation, installation view. Courtesy @warholfoundation. Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society.

Andy Warhol: Revelation, curated by José Carlos Diaz, the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, through June 19, 2022

Andy Warhol, that silver-haired Sphinx, was nothing if not a purveyor of paradoxes; any in-depth examination of his art and films has to face the mysteries posed by a vast body of work that is at once superficial and profound, cynical and sincere, brightly populist and cooly elite, ravenously fame-hungry and gnomically private. The exhibition Andy Warhol: Revelation, now on view at the Brooklyn Museum, offers a compelling and surprisingly fresh framework by looking closely at the significance of Warhol’s lifelong Catholicism. The show’s frisson begins with its very premise: many today would still be surprised to learn that Warhol, doyen of the New York demimonde, celebrator of queer sexuality, and fixture of the sybaritic celebrity jet-set, was the same creature who attended church services somewhat regularly on weekends, spent holidays with Catholic charities serving soup to the poor, thrilled at the opportunity to see the Pope and the Vatican in person, and, after his death in 1987, received a grand memorial service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, complete with eulogies delivered by men of the cloth.

Andy Warhol: Revelation, installation view. Courtesy @warholfoundation. Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society.

The question of how this private Warhol related to the public artist is the exhibition’s animating riddle, and it is explored to satisfying effect through numerous angles. One is the display of biographical relics that speak to his Byzantine Catholic upbringing, provided by his Carpatho-Rusyn immigrant family in Pennsylvania. Thus we are shown his mother’s coy pen-and-ink sketches of angels, selections from his and the Warhol family’s collection of crucifixes and other religious ephemera, and a series of early twentieth-century canvases of four saints, painted in a stiff Renaissance style by artist John Hegedus, that once graced the St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church of Pittsburgh, where Warhol attended countless services in his 1930s childhood. This latter quartet of artifacts helps us believe that we might glimpse far back into the artist’s psyche by witnessing the very icons that introduced little Andy to a reverence for images.

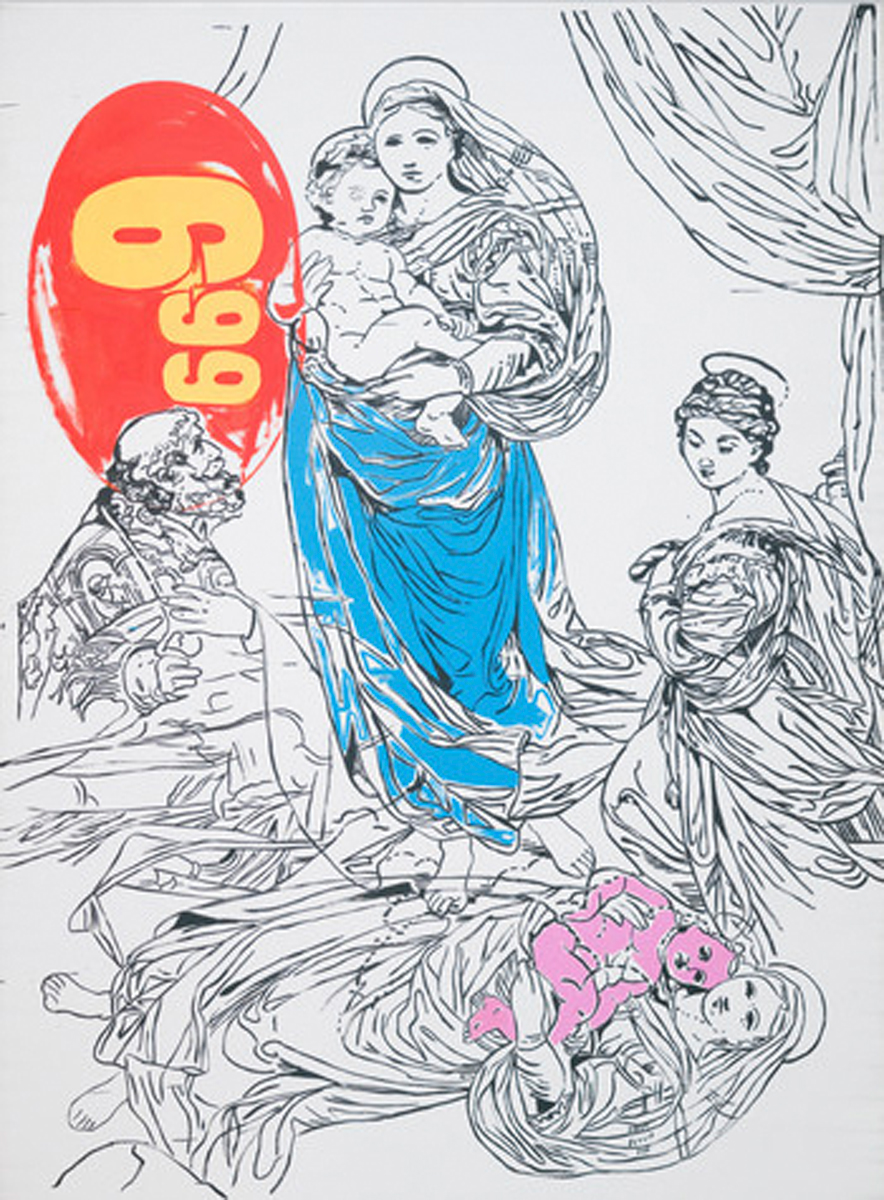

Andy Warhol, Raphael Madonna-$6.99, 1985. Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen, 156 1/4 × 116 inches. © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society.

The generous and varied selection of Warhol’s own artworks has been curated to demonstrate the use of Catholic iconography and themes throughout his career. Near the entrance to the exhibition stands his imposing Raphael Madonna-$6.99 (1985), a towering screen-print and acrylic remix of Raphael’s Sistine Madonna (1512–13) done in the style of a half-finished coloring-book image, with a huge red-and-yellow $6.99 price tag slapped near the adjoined heads of Mary and baby Jesus. In another context, the gesture might read as a comment on consumerism as a new religion, but here it’s hard to forget that the Catholic Church has long encouraged its own brand of aesthetic populism: theologically speaking, Raphael’s oil painting is no more or less sacred than the laminated reproduction found in a believer’s pocket. And indeed, Warhol’s Raphael Madonna reappears in the exhibition as a vitrined invitation for his St. Patrick’s memorial, now shrunk down to the humble dimensions of a prayer card, resized for more private remembrance and meditation.

Andy Warhol, The Last Supper, 1986. Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen, 78 × 306 × 2 inches. © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society.

Warhol’s debt to Renaissance religious painting, and the work of Leonardo in particular, is convincingly argued through many other instances, including numerous pieces from the Pop artist’s Last Supper series, which are among the final works he made for exhibition during his lifetime. A vast pink diptych reproducing Leonardo’s mural—simply titled The Last Supper (1986)—is given its own chamber; its source material was, naturally, itself a cheaply reproduced engraving of the original, similar to one found in the Warhol family home. Here the artist has magnified its dimensions as if to affirm the lowly copy’s power, or perhaps as a means, near the end of his life, to glorify a potent childhood memory.

Andy Warhol: Revelation, installation view. Courtesy @warholfoundation. Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society.

The range of work on view helps Revelation double as a Warhol retrospective in miniature, allowing viewers to move through both a focused, thesis-driven show and an overview of Warhol’s career in its many phases and fashions. For some, similar choices will have already been encountered at the Whitney’s extensive Warhol from A to B and Back Again just a few years ago, but Revelation summons some new undertones. Experiencing Warhol’s rarely seen Crowd photomontages (ca. 1963) at A to B was novel, bringing light to a largely unexamined early engagement with serial form and mass media: the nearly Op-Art arrangements were made from LIFE magazine photos of the throngs gathered at the Vatican. Here, placed near press photos of Warhol meeting Pope John Paul II in 1980, one can see more clearly a cruciform gap left open between segments of one collage, its spiritual nature peeking out of negative space. Small wall-mounted pieces made from Warhol’s own semen and urine now feel less like comments on body fluids in the era of AIDS and more as modern interpretations of the miraculous lacrimae of statues, or the mythical sweat and blood of the Savior that created the Veil of Veronica.

Andy Warhol, Reel 77 of **** (Four Stars), 1967 (still). 16mm film, transferred to digital video (color, sound), approximately 15 minutes. Courtesy the Andy Warhol Museum. © 2021 The Andy Warhol Museum.

As is sadly the case with many Warhol exhibitions, Revelation’s engagement with the artist’s film and video practice is meager, with only three examples from his over six hundred moving-image works on view, and two of these as excerpts. A video of his dual-16mm film The Chelsea Girls (1966), one of his best-known movies, is given its own black box to loop in its three-and-a-half-hour entirety; viewers will have to be lucky enough to stumble on the most relevant reel, in which amphetamined Ondine plays at being the Pope. In contrast to the well-appointed Chelsea Girls, a digital reproduction of the 16mm reel that MoMA has long titled Sunset—here granted the more precise appellation Reel 77 of **** (Four Stars) (1967)—is projected upon a mounted screen, with subtitles unacknowledged as additions to the original. The image washes out badly under the strong gallery illumination; there is nowhere to sit to experience the film over time (in contrast, The Last Supper, in the adjoining chamber, is given benches for contemplation). This is all the more frustrating since Reel 77—which was part of Warhol’s only commission funded by the Catholic Church (for a never-realized World’s Fair pavilion) and features images of a setting sun over the California coast, with all their hippie-spiritual grooviness—could have been an important centerpiece for this show.

A clip from I, A Man (1967) is displayed in a similarly overlit manner in order to feature Valerie Solanas, who—like Brigid Berlin, Holly Woodlawn, Joe D’Allesandro, Gerard Malanga, Paul Morrissey, the Kennedys, and so many others of Warhol’s circle—was raised Catholic. A robust engagement with Warhol’s cinema would have opened up many more of these connections, by including, say, one of Mario Montez’s screen tests, or Warhol’s life-of-Jesus parody Imitation of Christ (1967), or an excerpt from Lonesome Cowboys (1968)—funded with leftover money from the unfinished Church commission—in which Viva sings Kyrie eleison and Ite, missa est as she undresses with a muscular young man in the darkness. Revelation delves deeply into Warhol’s religion as formative for his interior life, but a better engagement with cinema could have highlighted the communitarian aspects of Catholicism that may have led to the emergence of such a congregation around him.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.