Quinn Latimer

Quinn Latimer

An Italian art critic and feminist activist interviews the patriarchy.

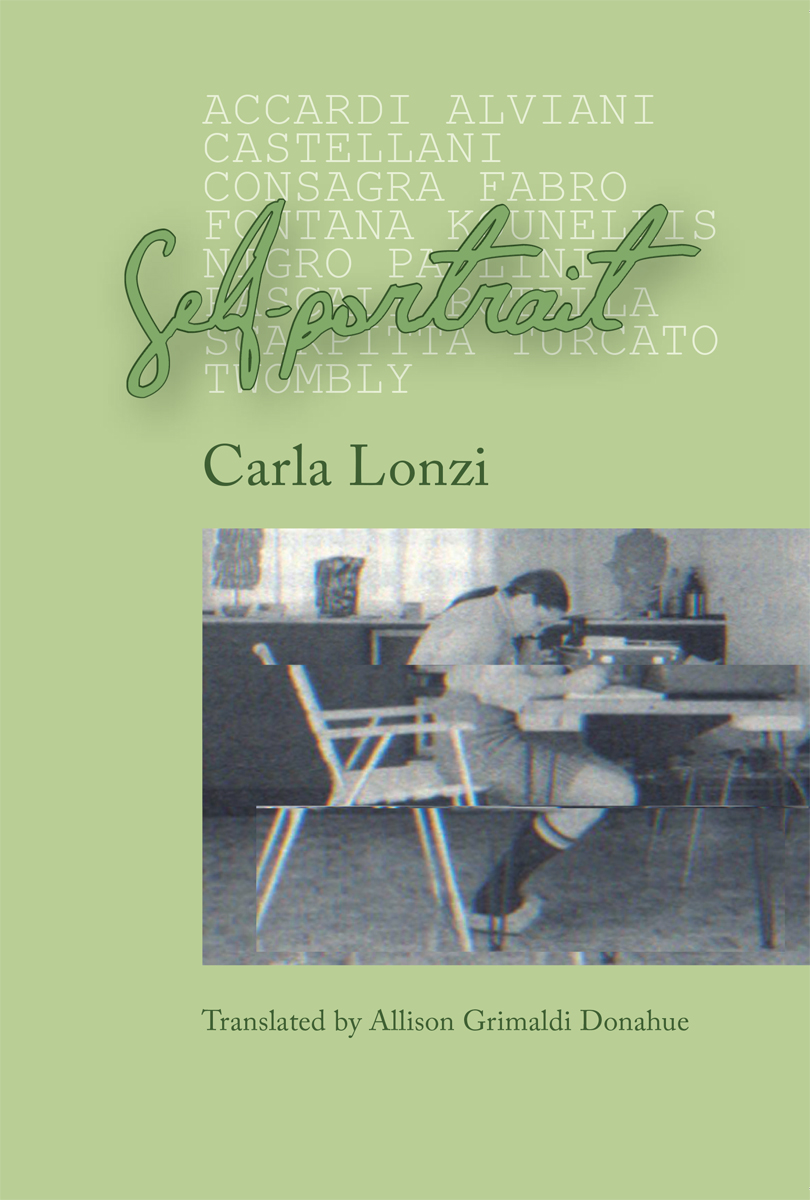

Self-portrait, by Carla Lonzi, translated by Allison Grimaldi Donahue, Divided Publishing, 362 pages, $18.95

• • •

There is a polyphonic perversity to Carla Lonzi’s Self-portrait, drawn as it is from interviews with thirteen white European and American male artists, as well as Lonzi’s sister in name and struggle, the artist Carla Accardi. When Lonzi notes that she believes the Gospel “that there is a concomitance between a word that is spoken and a person who awaited it,” one almost doesn’t believe her. Or I don’t. Not that Lonzi, the iconoclastic Italian feminist art critic, writer, curator, and activist, wouldn’t show up, every time, as a rigorously receptive receiver, but that these are the words—uttered by artists including Pietro Consagra, Lucio Fontana, and Jannis Kounellis—that she has been waiting for.

The artists Lonzi is in conversation with here are mostly men of their (and, tiredly, our) time. They talk at length about their many abstracted subjugations, the minutiae of their labor, new technologies and old tautologies, respect not shown, money not made. Self-portrait was published in Italy in 1969, the interviews recorded over that seismic decade, but the complaints, ideas, and sentiments do not sound so old. Patriarchy: same as it ever was. And yet there is pleasure, still, to be found in the collated voices, haltingly or fluently describing their artistic processes, and deftly translated into English for the first time by Allison Grimaldi Donahue.

What do voices do as they move from air to page? What is the strange thrill of seeing them rendered in writing, each casual or oracular line running like a nerve across paper, mouthing and manifesting the real, whatever that is? The idea of a real voice—attached as it is to a real body, real life, supposedly—has long animated critical literature. In Lonzi’s Italian, Autoritratto suggests some proto-autotheory, autoethnography, autofiction. Yet, we might better call her collaged transcriptions of interviews “montage,” as Accardi astutely does. Combing the interviews for affinities and affiliations, Lonzi edits passages of speech together like some conversation in which space and time collapse into a palimpsest; she acts like a writer, and also does not. Indeed, Lonzi’s ambition was to “find a page that isn’t a written page,” or was not, originally.

Reading Self-portrait, I kept thinking of the irradiating title of Lonzi’s later, pivotal book, from 1978: Taci, anzi parla: Diario di una femminista. “Shut up, or rather, speak.” It seems Lonzi might have been issuing this command backwards, to the male artists whose voices—often exhausting, occasionally beautiful and revelatory—she decided, oh so oddly, to delineate herself with. But Lonzi was always interested in getting as close as possible to the paradox and texture of things: art, language, relationships, women’s disenfranchisement, the grain of the voice itself (à la Barthes). An art critic who rejected the critical art system (“we’re waiting for criticism to get out of the way . . . that Signor So-and-So steps aside”), a writer bored and bothered by the author’s authority, a feminist activist who cofounded Rivolta Femminile and recorded the end of her partnership with Consagra in a dialogic text with him, Lonzi and her books are radical studies in relation, transcription, chorality. She stays close to the record, compiling evidence in the form of diaries, dialogues, and collaged conversations pulled from life, staged as art. She saw relationships as key artistic and activist productions, with essential aesthetic and political value. As visual artists experimented with material, she experimented with human relations and their most mineral communications, gleaning their depths for a more radical subjectivity. And in the spoken voice she received something, and then she wrote it down.

The voices of Lonzi’s Self-portrait move from colonial longings to get closer to nature to the economy of painting to Picasso’s wealth and De Chirico’s phosphorescent hands, to discussions of power and mysticism, language and image, eroticism and labor, the American artist versus the European gesture, the scatological versus the reproductive as a creative force. Lonzi repeatedly goads on the artists to tear into her profession, dismantling the art critic for neurosis, avidity, pedestrianism; it is wonderfully, weirdly masochistic. Just as metacritical, perhaps, is the heavy traffic between oral language and visual art, consistently remarked upon: “There was Malevich who said, ‘You want a painting, call me on the phone and I’ll tell it to you,’ ” Mario Nigro recounts. Getulio Alviani notes: “You speak: for me it’s really an object.”

Alongside the transparent pleasure of listening to Accardi, Kounellis, and Consagra talk about language, renunciation, maturity, and love, and the savant-like Salvatore Scarpitta compulsively, fantastically describe his racing cars, there is Pino Pascali’s and Giulio Turcato’s casual bigotry, Lucio Fontana’s self-aggrandizing pettiness, Mimmo Rotella’s misogyny. Yet at any gathering you will find yourself stuck in a corner with someone who won’t shut up, while those who you’d like to listen to glitter softly across the room. But even the bore, talking at length, becomes sympathetic somewhere in his story, should you remain to receive it. Likewise, Lonzi encourages you to stay, to listen, to take part in this conversation, which is art, which is life. Though Lonzi’s seriousness of endeavor is clear, levity does arrive in her labyrinthine questions to Cy Twombly, which are uniformly answered with: “(silence).” Too, when after listening to Luciano Fabro discuss a work he failed to make because he didn’t know how to find the necessary swaddling bands for a newborn, Lonzi replies: “I can give them to you . . . I still have some,” and Fabro, uninterested, quickly moves onto the difficulty of making a good cast of an erection.

Born in 1931 in Florence, where she would go on to study literature and art history with Roberto Longhi, Lonzi died at age fifty-one in Milan. A little more than a decade later, Annemarie Sauzeau curated an homage to Lonzi at the 1993 Venice Biennale. A life-size 1968 photo offered Lonzi at her typewriter (shades of that Rosalind Krauss pic), her head bent toward a tape machine as she worked on the recordings that constitute Self-portrait. The image also covers this first English edition (in a wonderful design by Allison Katz). The original Italian publication, meanwhile, featured a cover image of one of Fontana’s cut canvases. Read against Lonzi’s feminist path forward, Fontana’s work evidences a clear clitoridean quality, a reading that I am sure he would have hated.

In the current cultural moment, certain words keep appearing, like coins or koans. “Care” is one; “listening” another. Both are not to be taken literally by those who mostly voice them; they are code for other concerns. But Lonzi took listening literally. She believed that by listening to artists, one became less detached and more implicated, closer to an ethos of relation, through a subtle demystification of the artist that might occlude commodification. Yet Self-portrait’s methodology was also exit strategy: “If you take a recorder it means that, as a critic, you no longer exist in the traditional sense.” Lonzi was not interested in tradition; she saw and heard what it did. Self-portrait was her means to leave criticism, as well as the patriarchal system of male artists it so fastidiously attended.

Lonzi ends Self-portrait—nearly four hundred pages of mostly white men talking—with Accardi commenting, haltingly, on the “woman-man” problem, old as time. The following year, in 1970, Lonzi, Accardi, and Elvira Banotti published their Manifesto di rivolta femminile, which concluded with the statement: “we communicate only with women.” Lonzi had left the men to talk amongst themselves, their receptive interlocutor and confidant no longer. The next manifesto from Rivolta Femminile, issued in 1971, would be even clearer, its title as cutting as crystal: Assenza della donna dai momenti celebrativi della manifestazione creativa maschile. Or: “On woman’s absence from celebratory manifestations of male creativity.”

Quinn Latimer is the author of Like a Woman: Essays, Readings, Poems (Sternberg Press, 2017). Her writings have appeared in Artforum, the Paris Review, Texte zur Kunst, The White Review, and elsewhere. She is co-editor of Amazonia: Anthology as Cosmology, just out from Sternberg Press.