James Hannaham

James Hannaham

MoMA PS1 tries to recapture the maverick director’s work.

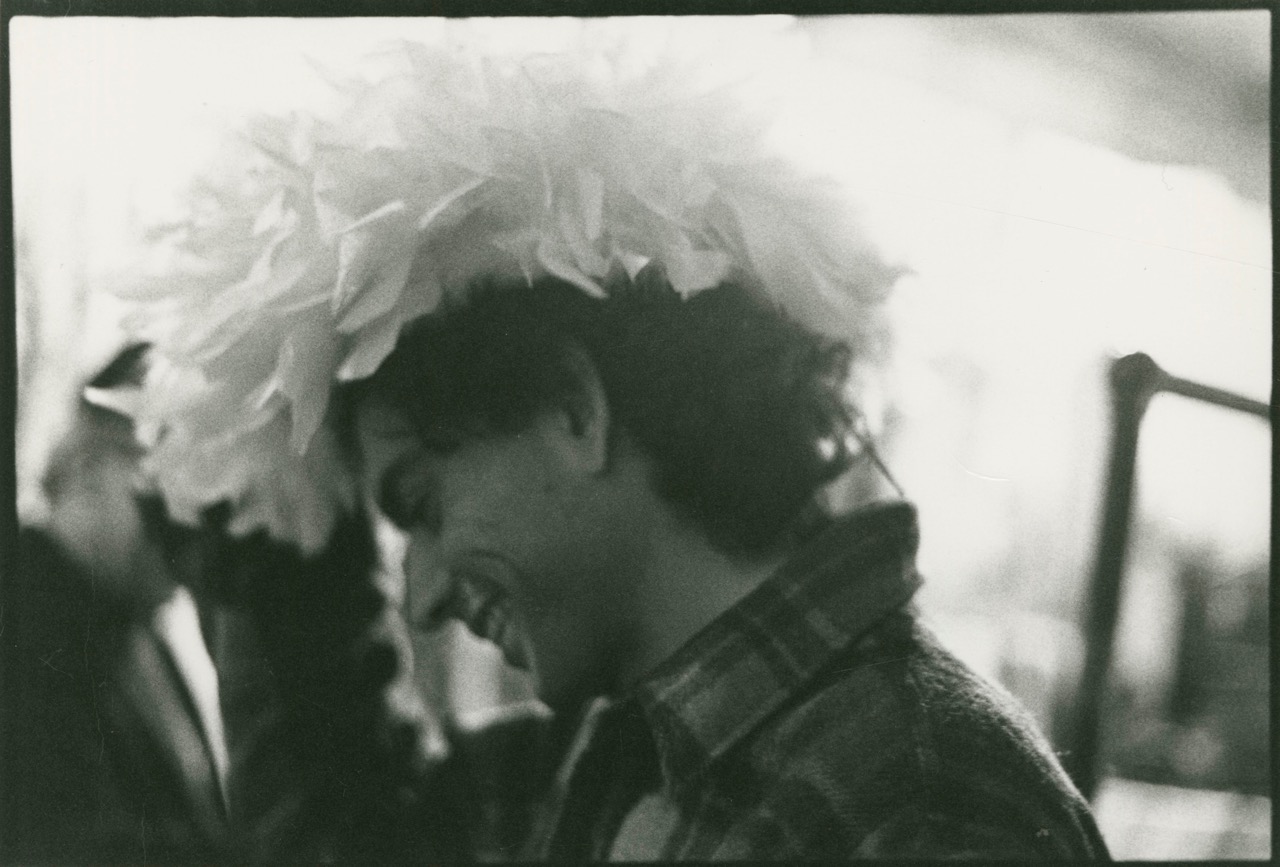

Reza Abdoh. Photo: Richard Liebfried.

Reza Abdoh, MoMA PS1, 22–25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, New York, through September 3, 2018

• • •

Reza Abdoh, being commemorated with a puzzlingly insufficient retrospective at MoMA PS1, blazed through the performance world like a comet—his career was brief, bright, mysterious, and intense. The theater director’s major works—with his company, dar a luz—all appeared between 1990 and 1995, when Abdoh died of AIDS. Yet the term “theater director” seems inadequate; one might also call him a ringmaster or auteur, so to showcase the work in an art museum seems apt. Even so, PS1 can neither contain his complicated, excessive vision nor represent it faithfully. Hopefully anyone new to his brilliant extravaganzas will seek fuller satisfaction elsewhere.

Abdoh’s singular sensibility proves difficult to describe: imagine if the Wooster Group had been an out gay Iranian artist who settled in Los Angeles and cast multimedia performances with actors as skilled as anyone produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company and as trashy as anyone filmed by John Waters. Imagine these actors attacking scripts that dealt audaciously, even pornographically, with vital issues like racism, homophobia, and AIDS, to name a few. Keep imagining; Abdoh often laid the scenarios for these shows onto a framework of classic world literature, which he then mixed with television, current events, and popular culture long before the term “mashup” was invented—one piece from 1990 is titled The Hip-Hop Waltz of Eurydice. Imagine as well a relentless feverishness and physical risk onstage that was often frightening, and that resonated with precursors and contemporaries like Charles Ludlam, Diamanda Galás, Ethyl Eichelberger, La Fura dels Baus, Karen Finley, and, of course, Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty.

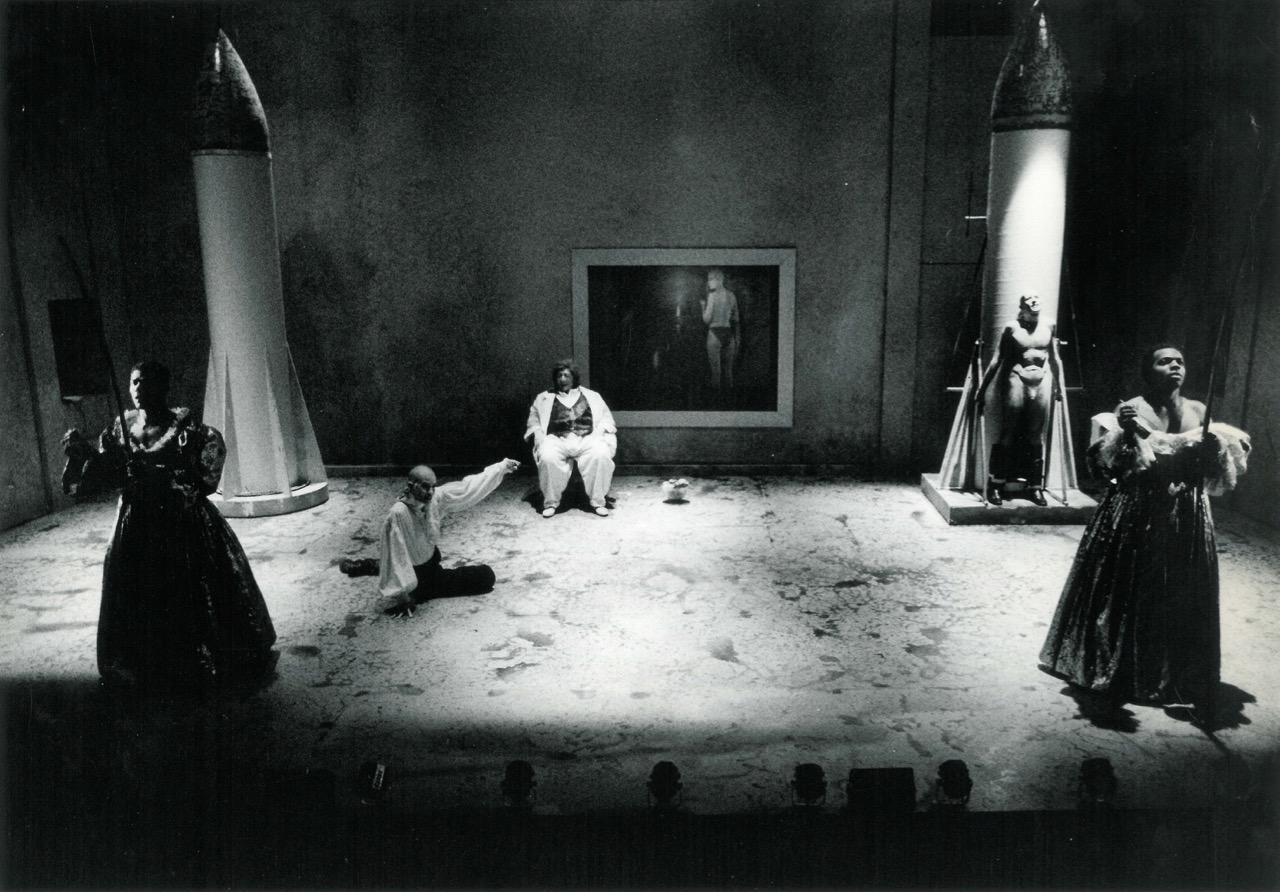

Reza Abdoh, The Hip-Hop Waltz of Eurydice, 1990. Photo: R. Kaufman.

Abdoh’s stagecraft was improbably thrilling, akin to living inside an outlandish music video for two or three hours. That his career represented the zenith of so many cultural strands yet turned out to be the end of so much is among the saddest things that happened to performance in the 1990s. Keeping Abdoh’s memory alive feels important and welcome, especially at a moment when defiance of the status quo has become urgent and vital.

The difficulties of representing this man and this body of work, however, are evident all over MoMA PS1’s survey, which is hamstrung by its layout and undone by its frustrating mixture of ambition and apprehension. The show begins with a series of wall-text timelines weaving Abdoh’s biography with the historical events that shaped his life—the Iranian revolution, the AIDS crisis, the 1980s LA punk and club scene. The text is sometimes interrupted by wall-mounted TV/VCRs that play excerpts or entire video documentation of Abdoh’s early work.

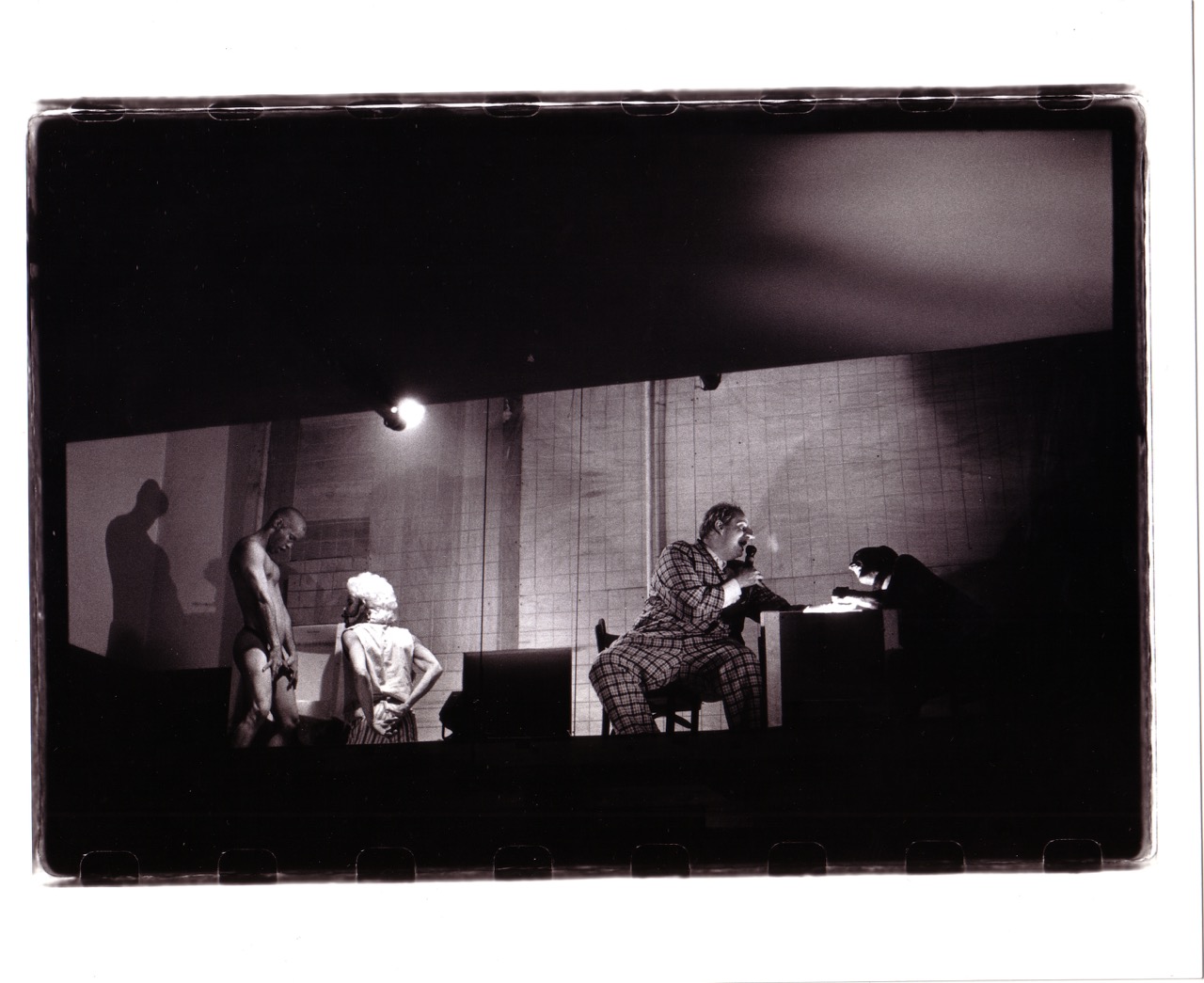

This is informative, but the exhibit then opens out into a series of larger rooms, with several videos of shows or interviews with Abdoh projected onto entire walls, playing on loops. Some of the videos run two or three hours long. The curators have installed doors between a couple of these larger rooms, which one might think they’d put in to keep noise from the videos from seeping into the wrong rooms (though that doesn’t work); in fact the doors are meant to evoke a theater, but they don’t. It seems as if, for the sake of having a big show that fills the space, the exhibition has sacrificed much of the viewer’s ability to see and hear anything subtle about the work. While all the reverberant, overlapping dialogue heard through doors makes the environment sound like a giant premillennial controlled-chaos echo chamber, which feels appropriate, the overwhelming sensations discourage engagement with individual productions (which were designed to overwhelm, of course, but not merely with energy and volume). Viewers will tend to enter these rooms long after a video has begun, find themselves briefly stunned by grainy images of a deeply committed, often half-naked ensemble navigating a high-tech set—for example, The Law of Remains (1992), an Andy Warhol/Jeffrey Dahmer mélange vigorously protesting homophobia and racism—hear the actors shouting ardently (thanks to the director) and unintelligibly (thanks to the shoddy audio of the day), and move on without getting much of a grip on the piece.

Reza Abdoh, The Law of Remains, 1992. Photo: Paula Court.

It may be too much to ask of an art space to give a truly focused sense of each work by an artist so devoted to visceral presence. So while the raucous side of dar a luz comes through, a lot gets lost: the group’s many moments of quiet intensity and theatrical skill, the Genet-like, sleazy lyricism of the writing, often by Abdoh and his brother Salar (who later became a novelist), and the detail work on some gorgeously creepy costumes and scenic design, which the blown-up video blurs.

Reza Abdoh, Tight Right White, 1993. Photo: Paula Cort.

Tight Right White (1993), a purgative circus of racist imagery culled partially from the unfairly maligned exploitation film Mandingo and other sources, creates further problems for the museum, which has placed a sign at the door warning audiences about the exhibition’s graphic subject matter. Back in 1993, Michael Feingold, writing in the Village Voice, characterized TRW as “a psychological enema, shoved up the id of liberal theatergoers to expel the unhealthy imprints a racist society has deposited there.” If today’s public requires warnings about sexually explicit content, the museum apparently needed to double bag against racially charged, deliberately offensive fare. The exhibit does not include video of Tight Right White at all; in fact, Feingold’s comments, a feature article (also in the Voice) by Beth Coleman, a few production stills, and photographs of the cast provide the only documentation of that performance in the exhibition. One can sense the institution shrinking from several possible misreadings: some visitors may protest that no one should ever see this volatile material, others may find it impossible to neutralize, a few may get off on it.

Reza Abdoh, Tight Right White, 1993. Photo: Paula Cort.

The move, however, seems cowardly and faintly patronizing. Apparently we can live in Trump Country, hear his bluster, and watch the cruelty his policies wreak on people of color on a daily basis, and yet the work of an out gay Iranian who died twenty-three years ago, which turned outrageous stereotypes into art twenty-five years ago (in collaboration with a mixed-race cast), is somehow too much for the art-going public to bear. Would PS1 mount a retrospective of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s films without screening his infamously “disgusting” anti-fascist masterpiece, Saló? Based on their elision of Tight Right White, it seems likely.

Video of TRW is readily available online, so the curators clearly aren’t addressing a lack of documentation. The quality isn’t the best, but it’s no worse than footage of other pieces that made it into the show. They could’ve won the day by devising a clever solution to the complex problem of presenting this material in a society that today seems both more openly racist and more squeamish about confronting racism than ever. Even an unclever solution, like a second trigger warning or a “teaching moment,” would’ve come off more respectably, and furthered Abdoh’s intent—to expose the pervasiveness and tenacity of the attitudes that produced these images and eventually to banish racism. Avoiding difficult questions by omission and hoping nobody will notice is one reason they refuse to go away.

James Hannaham has published a pair of novels: Delicious Foods, a PEN/Faulkner Award winner and New York Times Notable Book, and God Says No, a Lambda Book Award finalist. He practices many other types of writing, art, and performance, and teaches a few of them at the Pratt Institute.