Nico Israel

Nico Israel

From the ludic to the civic: the sprawling exhibition liberates the

built environment.

16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, FREESPACE. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

La Biennale di Venezia 16th International Architecture Exhibition: FREESPACE, through November 25, 2018

• • •

FREESPACE is the emphatic, neologistic title of the latest edition of the Venice architecture biennial. It yokes the enterprise of shaping space to ideas of freedom—political conceptions about what constitutes liberty in an age of national retrenchments and fortified borders, but also more broadly the ability to create without constraint and to consider those things that are given to all of us. In their “Manifesto” for the biennial, curators Shelley McNamara and Yvonne Farrell, of Dublin-based Grafton Architects, announce that their intention for the exhibition is to celebrate “architecture’s capacity to find . . . unexpected generosity . . . even within the most private, defensive, exclusive or commercially restricted conditions,” while also striking a Don Draper–meets–Martin Heidegger tone when they declare, “We see the earth as Client . . . Architecture is the play of light, sun, shade, moon, air, wind, gravity in ways that reveal the mysteries of the world. All of these resources are free.” Whether their besieged Client is pleased with the results is hard to say. But the biennial, with its attunement to both constraint and potentiality, is engrossing and memorable.

This is no small accomplishment given FREESPACE’s sprawling scope. Its sixty-three national pavilions and over seventy other participants occupy the Giardini, the Arsenale, and spill out elsewhere into the city of 118 islands.

Czech and Slovak Republics Pavilion: UNES-CO. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

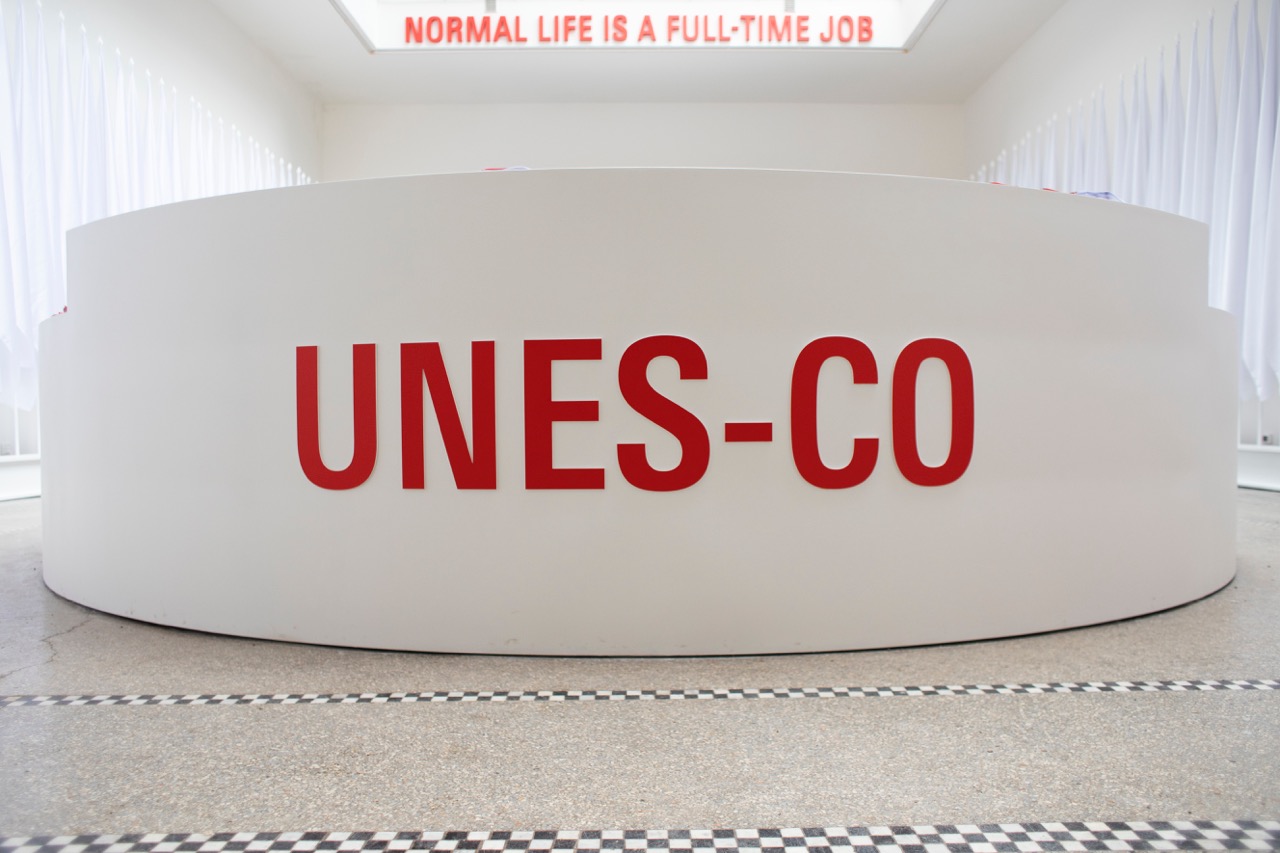

The most biting and genuinely site-specific entry among the national pavilions is UNES-CO, the Czech and Slovak offering. Focusing on the UNESCO World Heritage–designated Czech town of Český Krumlov, UNES-CO addresses in miniature the situation of the much better-known and grander Venice: in both cities tourism is at once lifeblood and, because of high cost of living and resultant depopulation, existential danger. UNES-CO is an art project–cum-company created for the purpose of providing, for a period of three months during the biennial’s run, free accommodations and a living wage to qualified applicants willing to live in Český Krumlov’s town center. The new residents, who are required to perform a set of “normal life” tasks—“reading a book/newspaper on a bench, walking a dog along the streets, going for a stroll with a baby carriage on the square,” etc.—“breathe life” into the city, yet in a revealingly troubling way.

Israel Pavilion: In Statu Quo: Structures of Negotiation. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

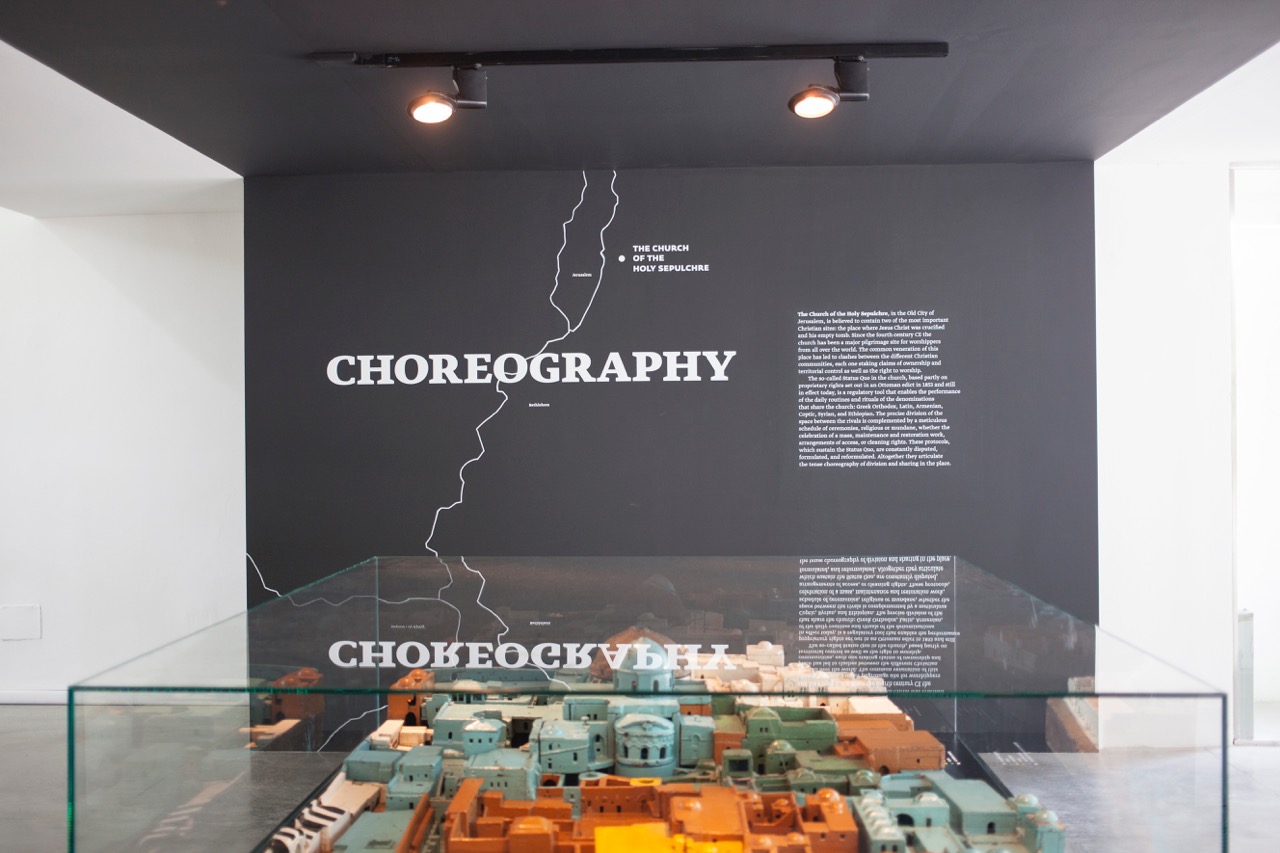

In Statu Quo, Israel’s entry, explores how competing claims to religious sites in the Holy Land have been negotiated over the last 1,500 years, including Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall/Temple Mount and Church of the Holy Sepulchre (which various Christian denominations share), and Rachel’s Tomb in Bethlehem. One display in it, accompanied by a video installation by Nira Pereg, investigates the temporary solution devised for sharing the Cave of the Patriarchs/Ibrahimi Mosque in the occupied Palestinian city of Al-Khalil (Hebron), for centuries a place of worship for both Jews and Muslims. After the 1994 massacre of twenty-nine Muslims in the Cave/Mosque by an ultra-orthodox Jewish Brooklynite, the Israeli army erected a bulletproof wall that divides the site, with each religious group allocated a separate area. But on twenty holy days a year the entirety of the space is given over to a single religion, and decorated exclusively with that faith’s artifacts. The film’s focus on this now-routine religious shift-change reveals a contingency of belief in relation to territory, and arguably serves as a counter-narrative to the militaristic-theocratic ambitions of Israel’s current government. (The US embassy move to Jerusalem and events at the border with Gaza unfolded during the biennial’s first month.)

Switzerland Pavilion: Svizzera 240: House Tour. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Other presentations emphasize the more playful aspects of FREESPACE. Golden Lion–winner Svizzera 240: House Tour looks like a full-size house from the outside, but its interior consists of a labyrinthian series of rooms built on different physical scales, all spliced together. One of these scales resembles mass-produced homes constructed in Europe and the US in the decades after World War II, while other rooms ramp up or take down scalar features—doors, windows, beams, and power outlets are much larger or smaller than expected—resulting in some jarring Lilliputian and Brobdingnagian perspectives. Unsurprisingly, it is the most selfie-friendly of all of the exhibits in the biennial.

Nordic Countries Pavilion: Another Generosity. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

In the Nordic Pavilion, Another Generosity features large, membrane-like white balloons filled with water and air, which inflate and deflate as viewers walk through the space—rather like inhuman versions of the figures in Gary Hill installations responding to your presence. These cumulus, cell-like structures with their wires attached to the ceiling are (according to pamphlet text) intended to show “how architecture can facilitate the creation of a world that supports the symbiotic coexistence” of nature and the built environment, but their staging in a virtually all-white space evoked, in a not-unfavorable way, a Matrix-like automobile showroom of the future.

Michael Maltzan Architecture, Star Apartments, 2018. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

The Central Pavilion includes a display of Michael Maltzan Architecture’s Star Apartments, a completed project to house 102 long-duration homeless people in Los Angeles in a permanent structure retooled from a former commercial space. A floor-to-ceiling mural shows the site of the building on the edge of the Skid Row section of the city and gives a sense of the environs; a large architectural model highlights the building’s common areas (wellness center, community kitchens); videos feature tours of how residents have personalized their spaces; and a diorama includes photographs of objects that residents identified as their most important belongings. Numerically speaking, the residents housed here are a drop in the bucket—tens of thousands of people live in cars and tents on LA’s streets and sidewalks—but the project demonstrates what a widespread socially committed architecture might produce.

Flores & Prats, Liquid Light, 2018. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

In the Corderie, a former rope factory and now mammoth exhibition space, Catalan studio Flores & Prats have placed a fragment of their Sala Beckett, a lovingly refurbished theater in Barcelona. Titled Liquid Light, their exhibit reveals, through various media, the complex history of the site, a former workers’ cooperative building that had been abandoned for almost three decades before Flores & Prats revived it. Pigeons and rain had made a hole in the roof, and in their renovation the architects preserved the hole so that “a ray of light right at the center of the old scenery” could penetrate. It’s difficult to know what the exacting and notoriously private Samuel Beckett would have made of this slightly ham(m)-fisted gesture, much less of a theater being named for him. Yet there is something poignant about the tribute, and indeed about the earnest approach of many of the projects on view in the biennial, which in their own ways could be said to draw political and artistic inspiration not only from the idea of FREESPACE in a manifestly unfree world, but from the titular invocation in one of Beckett’s most haunting texts, Comment c’est—which means “how it is” while also containing a command to begin: commencez!

Nico Israel is a professor of English at the CUNY Graduate Center and Hunter College. His latest book, Spirals: The Whirled Image in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art (Columbia UP), has recently come out in paperback.