Josh Kun

Josh Kun

A scramble across geographies: the drummer’s first album as a band leader gets reissued.

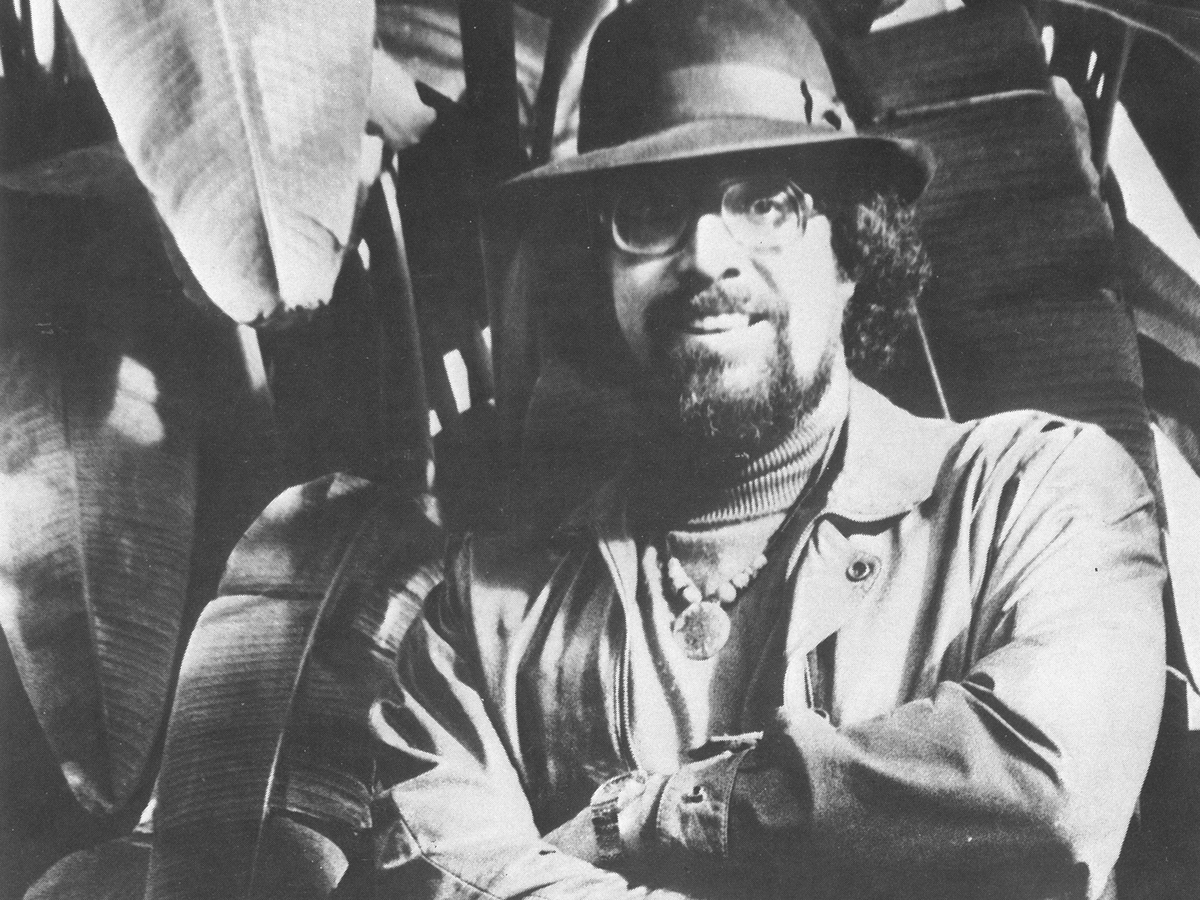

Francisco Mora Catlett. Courtesy Far Out Recordings.

Mora! & Mora! II, by Francisco Mora Catlett, reissued by

Far Out Recordings

• • •

As a drummer, Francisco Mora Catlett thinks in time, space, and rhythm. He keeps time, but also bends it, holding the past in the pocket of the present, while mixing the meters of a future that he shapes as he plays. He creates space through cadence and feel, and travels across the geographies that unfold: maps, histories, landscapes, oceans. The rhythmic language he speaks is ample and expansive, but specific, the deep diction and fugitive grammar of the Black diaspora. With his hands, he sends and receives waves of capture and escape. And joy. Mora Catlett plays with, and through, a ton of joy.

Francisco Mora Catlett. Courtesy Far Out Recordings.

The first thing we hear on his newly reissued first album as a band leader, 1988’s Mora!, is a dawn chorus of birdsong. Then come the drums. They only last a minute. Calloused hands on stretched hides, stretched hides on carved wood. Music made of felled trees and flayed animals.

You can hear the batá drum the loudest. Traditionally assembled in Nigeria with wood from the Oma tree, the batá is a Yoruba ceremonial instrument, palmed and slapped to conjure deities and divine ancestors. Batá sounds singular but is actually plural; never one drum, always three. It is a self-contained communication system, a conversation apparatus, with each drum playing a specific role: one calls, one answers, one keeps time. The batá left Nigeria with the hands that touched it, on slave ships headed to Cuba, where the ceremonies began to change and the conversations took place in new languages. An African instrument that became a building block of music in the Americas, the batá belongs to here and there, and is intimate with dispossession.

The batá’s knowledge of both Africa and the Americas, spirit and earth, chains and flight is part of the code of both Mora! and its sequel, Mora! II (available as a complete set by London’s Far Out Recordings). The albums scramble that code across geographies—Nigeria and Cuba, but also Haiti, Brazil, and the US—and across kinships with bells, timbales, steel drums, saxophones, flutes, and strings.

Mora Catlett recorded the albums in Detroit, in 1988, with some of that city’s top jazz players, including pianist and founder of the local Strata label Danny Cox, and Motown alum and member of the Tribe Records collective Marcus Belgrave. But he didn’t use “jazz” or any other genre tag one might reach for to describe his music: Latin jazz, samba, rumba. Instead, he called it “Afro-Euro-Indio-American Music,” defining it according to the places and cultures that birthed it and that it moved across. He created his own label, Americas Authority Creative Experience, to release the albums and named his band Amigo.

His approach bears the distinct stamp of one of his teachers, Sun Ra. In 1974, Mora Catlett was in the audience when Sun Ra and his Arkestra performed at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. By then, Mora Catlett had played drums on Mexican film and TV studio sessions, anchored the ’60s garage rock quartet Los Profetas, and studied with Nigerian percussionist Babatunde Olatunji. Mexican jazz hadn’t yet broken too many rules. Ra was calling what he made Cosmo Equation Infinity Music, and at Bellas Artes he unleashed a demo: synth squawks, feedback baths, choral chants of space travel, and an opening five minutes of ecstatic improvised drumming. After the show, Mora Catlett talked his way into a spot in the Arkestra, played with Ra in front of the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacan (and, incredibly, on the Mexican TV variety show Siempre en Domingo), and stayed with the band for the next eight years.

Francisco Mora Catlett. Courtesy Far Out Recordings.

Ra also introduced Mora Catlett to Henry Dumas’s short story “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” about a Black musician named Probe who plays a mythical all-powerful instrument, the Afro-horn (Mora Catlett would later take “Afro-horn” as a sort of artistic moniker). At a jazz club named Sound Barrier, a group of white fans force their way in and demand to listen to Probe play, taking a spot right next to the stage. What they don’t know is the horn does not simply blow sound or “play jazz”; it blows a diaspora hurricane, a cyclone of Black communion so strong that it levels anyone standing in the way of its path.

The Mora! sessions were Mora Catlett’s first post-Ra recordings as leader. Together they form an epic song cycle that extends a map-blurring tradition of pan-African and pan-American musical suites set by the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Gato Barbieri, and Flora Purim. The latter’s ’70s work is particularly felt on tracks like “Samba de Amor” and “Amazona Dawn Prelude” when the vocals of Teresa Mora (Mora Catlett’s then wife) soar over berimbau, flutes, steel drums, and a blitz of batucada. The end result is as much exploration as argument. Follow the drum out of Africa and into the holds of ships, and the history of music in the Americas reveals itself.

Questions posed on I are answered on II. Where does the forest birdsong take us? Mora! asks. To the beach, says Mora II. What becomes of the fluid piano lines and tenor-sax runs of “Afra Jum”? asks Mora! They kindle the carnival of horn honks, timbales, and steel drums of “Afra Jum Pt 2,” says Mora! II.

While Ra’s musical influence occasionally pops up across both albums—the unbounded style shifts, the communal shouts and hollers, the melodies that burst into din—Mora! and Mora! II diverge from Ra methodologies in a key way. Ra famously “found earth boring” and chose instead to explore other places—universes, planets, planes, destinies—to both imagine and materialize new ways of living. Mora Catlett’s music, while equally immersed in myth and history, chooses to stay grounded. He finds earth full of possibility, nutrient rich and root laden, ready for the seeds of whatever is meant to grow next.

The debt for that approach might be owed to Mora Catlett’s parents, African American painter and sculptor Elizabeth Catlett and Mexican artist Francisco Mora. He dedicates Mora! to them both. Affiliated with the Black freedom struggle in the US and the radical print collective Taller de Gráfica Popular in Mexico, they were active in shaping revolutionary art movements on both sides of the border that embraced social realism as a technique of opposition and protest.

In 1992, Elizabeth Catlett painted a color lithograph she called Singing Their Songs, inspired by a Margaret Walker poem that begins with enslaved men and women singing dirges, ditties, and jubilees. The poem ends with a prayer: “Let a new earth rise. Let another world be born.” On Mora! and Mora! II, with the drum as his trowel, you can hear Francisco Mora Catlett digging in as a way of digging out.

Josh Kun is an author and cultural historian whose books include Audiotopia: Music, Race, and America; The Tide Was Always High: The Music of Latin America in Los Angeles; and Double Vision: The Photography of George Rodriguez. As a curator, he has worked with SFMOMA, the Getty Foundation, and many other institutions. In 2016, he was awarded a MacArthur “genius” Fellowship. He is currently writing a book on music and migration for MCD x FSG.