Sowon Kwon

Sowon Kwon

The Korean artist seeks to evade surveillance society.

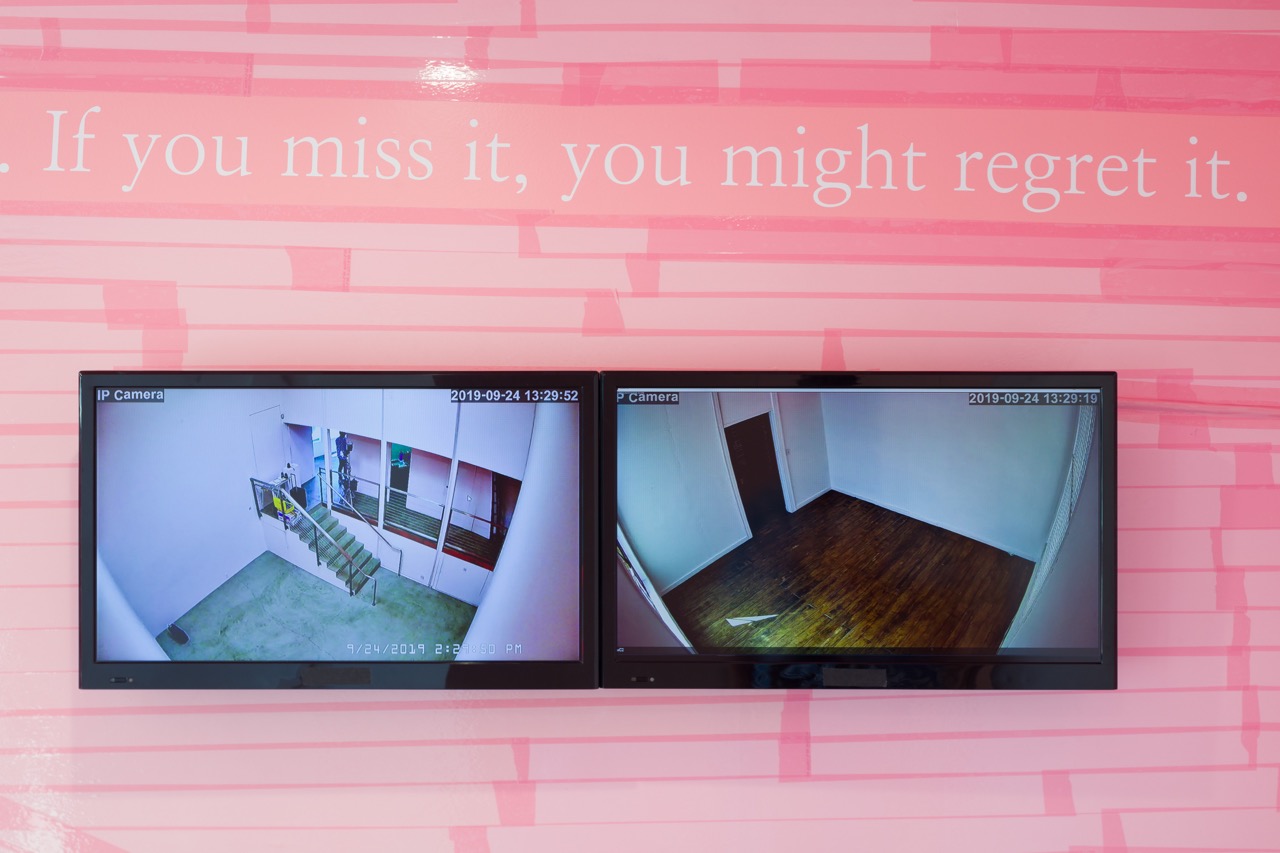

Inhwan Oh: My Own Blind Spots, installation view, Baik Art. Image courtesy the artist and Baik Art. Photo: Michael Underwood.

Inhwan Oh: My Own Blind Spots, Baik Art, 2600 South La Cienega Boulevard, Los Angeles, and Commonwealth and Council, 3006 West Seventh Street, Los Angeles, through November 2, 2019

• • •

Inhwan Oh’s Looking Out for Blind Spots (사각지대 찾기)—a densely layered, ongoing multimedia project—was first exhibited at Seoul's Willing and Dealing/Factory in 2014, and subsequently at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in 2015, earning Oh the prestigious Korea Artist Prize that year. His solo US debut, My Own Blind Spots, brings variations on the project to two LA venues, many of the works tailored and reenvisioned for the new sites.

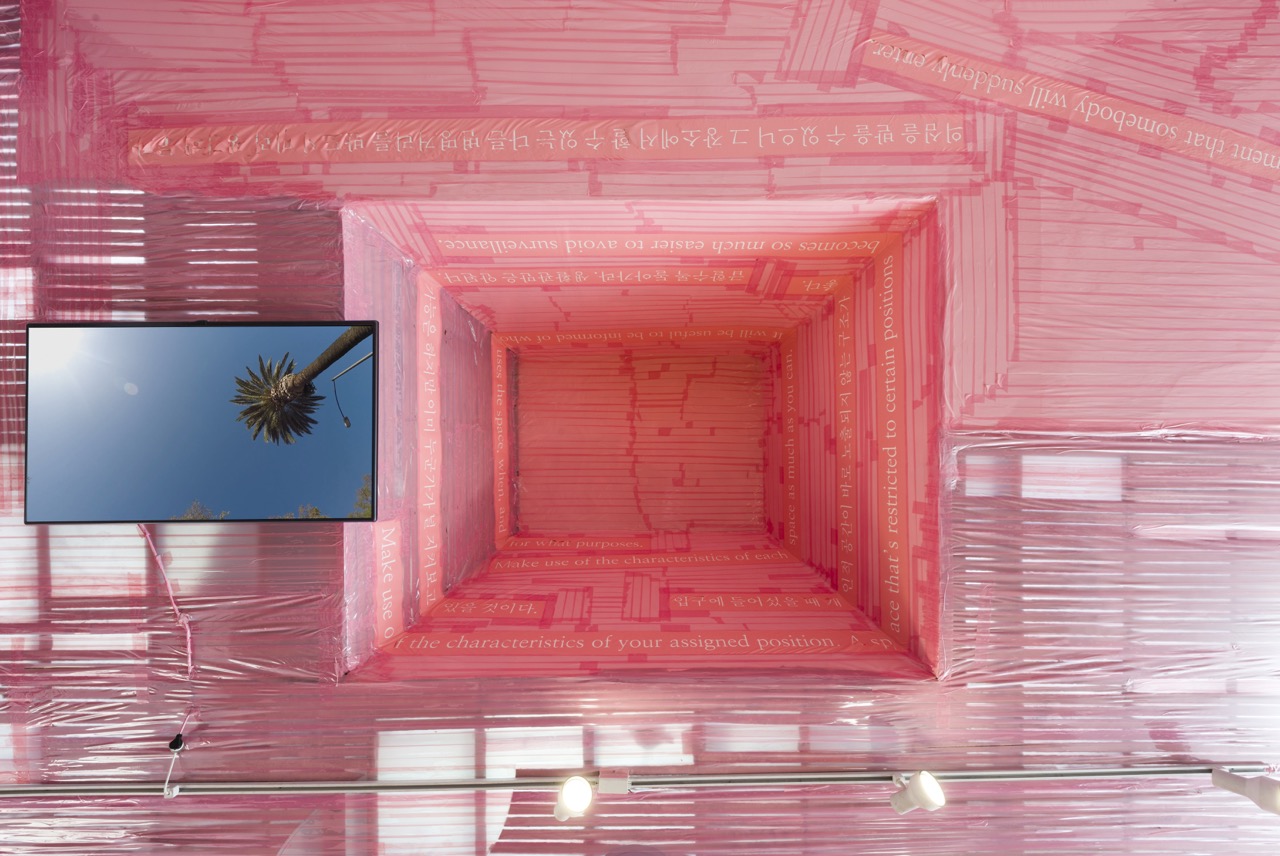

Inhwan Oh: My Own Blind Spots, installation view, Commonwealth and Council. Image courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

At both Baik Art, a relatively pristine commercial gallery in Culver City, and Koreatown’s grungier Commonwealth and Council, interstitial nooks, nondescript corners, recessed cavities and sundry protrusions in the ceiling would likely go unnoticed if they were not all highlighted in bright, translucent pink. The main exhibition walls are flanked by swaths and patches of the same pink, bounded within long transversals and acute angles. The bold spatial and graphic impact of Oh’s work is all the more striking upon closer look, for the simplicity and utility of its main material, packing tape—that commonplace workhorse of provisional adhesion—which has been attached in bulk and latticed in neat strips running varying directions, most the length of an individual’s arm span.

Inhwan Oh: My Own Blind Spots, installation view, Baik Art. Image courtesy the artist and Baik Art. Photo: Michael Underwood.

The pink tape is one component of the site-dependent Reciprocal Viewing System (2014–ongoing), which in this iteration pairs monitors at the entrance of both exhibition venues, displaying live-feed surveillance footage from cameras in situ within the galleries and at the partnered site synchronously. It’s a quick double take before the logic of the work reveals itself: the pink tape is not at all visible on the feed; it falls outside the camera’s limited field of vision. Tape can mask, but in this case, it also reveals that which the cameras do not see, reminding us by extension of the blind spots of similar tools of panoptic authority and control. Privy to the mechanics of the setup and the architectural intervention, we not only see and are seen alongside others, but can also slip in and out of view, at will. This capacity affords some respite, in our time of ever-higher-res Internet Protocol cameras, those armed with night vision, AI, and facial recognition software, when it can feel as if we are just hanging on to our civil liberties.

Inhwan Oh: My Own Blind Spots, installation view, Commonwealth and Council. Image courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

Mounted on the pink-taped walls in adjacent rooms at C&C are two sets of interviews on separate monitors. In My Blind Spot—Interview (2014–15), discharged soldiers give testimony on their efforts to find private time and space during their training (two-year military service is compulsory for young Korean men). Tightly framed from the waist up and somewhat claustrophobic in 9:16 vertical orientation, the participants are dressed in standard-issue fatigues against a backdrop of a similar forest camouflage motif. Both flattening out compositionally while also remaining in sharp contrast against the pink walls, the men are in effect “hidden” in plain sight. Soldiers around the time of the Iraq War, they offer a rare glimpse into one aspect of the homosocial world of conscripted life. They speak frankly, dutifully, even clinically, about their challenges and resourcefulness in locating guard houses and supply rooms, ammo dumps and bathroom stalls, a roof top, an old jeep—using these for rest, reading porn, masturbating, meditating, and in one instance of mirthful candor, nude tanning. They speak less of the risks if caught: of censure, ridicule, persecution, and, for higher-ranked officers, as noted by a former military policeman, of erasure (“as if you are not there”).

Inhwan Oh: My Own Blind Spots, installation view, Commonwealth and Council. Image courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

Excerpts from the interviews in Korean and English are rendered in vinyl wall lettering in a similar gauzy peach/pink that is interwoven into the tape throughout the installation. Instructions and advice range from practical (Be ready for the moment that somebody will suddenly enter) to sanguine (Observe. There are patterns in the military. The answer is in the limited space and timetable) to pithy and oblique (Genius steals. Steal the know-how of a sergeant about to be discharged from his service) to commiserative (Don’t feel guilty. Everyone, including you, does this somewhere).

Inhwan Oh: My Own Blind Spots, installation view, Commonwealth and Council. Image courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

On My Way to Blind Spots—Los Angeles (2019), a video shot by Oh with the camera pointed continuously skyward, is fittingly mounted on the ceiling. The sequences on-screen are marked by sudden shifts and repeating lags in movement, as if in tempo with an effort to follow the directions given in the audio: a compilation of instructions culled and scripted from interviews with soldiers recited by an automated voice (more Alexa than Siri, I would say). Overlaying directives from a different spatial, temporal, and cultural context, Oh navigates spiral staircases, cramped hallways and doorways, HVAC systems and dead ends, large fields with tall trees, past signage for a coin laundry, a restaurant, a barbershop, the side of a truck that suggests we may be in the parking lot of a VA hospital. A palm. More sky, the expanse that is greater Los Angeles. In Korean, “blind spots” (사각지대) has little ambiguity, with greater negative resonance than in English, connoting danger and, etymologically, even death. For Oh to actively seek them out is to, as one of the former soldiers advises, Be brave. This work invites the possibility of becoming freshly, if vertiginously, lost, but with that, of open-ended discovery.

Inhwan Oh, On My Way to Blind Spots—Los Angeles, 2019 (still). HD video, color, sound, 11 minutes 43 seconds. Image courtesy the artist.

I first learned something of the wide scope of Looking Out for Blind Spots online, soon after it opened at the MMCA and Oh was awarded the Korea Artist Prize. In scrolling through the news and media PR, two things struck me then, as now. One: for the celebratory events, the camera-shy artist had hired an actor to play him. On the KAP website today, said actor is still graciously accepting Oh’s bouquet at the awards banquet and still entirely convincing at his press interview. The footage is intact, if now with a disclaimer that reveals the playful charade, as if it were a studied, high-minded performance about authorship. Two: some surveillance footage. Not, per usual, of glitching scenes of urban ennui, or shoplifting teens, or idling traffic at intersections, but rather of the silent and fleeting presence of a lone dancer waltzing in triple time, swirling and floating in and out of view, as the tight confines of the gallery sub for a makeshift ballroom. Apropos of Oh’s proposition of the ephemerality of blind spots as liberatory spaces, I was unable to find the dancer again in my research for this review. But the memory of his moves, his grace and stealth, like that of a romantic cat burglar, is still strong and sweet.

Oh’s formative art education was at Hunter College in late 1990s New York City, some years after inverted triangles of a pink not dissimilar from his were righted. Against a black background and emblazoned with the words Silence=Death, the iconic image remains an enduring emblem for AIDS and LGBTQ activism. In 2017, at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in Soho, the Silence=Death Collective added onto the formula further instructions: Be Vigilant. Refuse. Resist, guiding us all perhaps to add our own. Oh’s might read: Look up as much as around. Keep moving. Play. And if you can, as in the stuff of true revolutions, dance. Dance two three, one two three.

Sowon Kwon is an artist based in New York City. Her exhibition Pattens comma is currently on view at MBnb in Harlem. Her work has also been featured at Full Haus gallery in Los Angeles, the Poetry Project, and Triple Canopy magazine. She teaches in the Graduate Fine Arts Program at Parsons The New School.