Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge

Multitudes of entrances and exits within a painter’s twenty-four canvases.

Allison Katz: Artery, installation view. Courtesy Camden Art Centre. Photo: Rob Harris.

Allison Katz: Artery, Camden Art Centre, Arkwright Road, London, through March 13, 2022

• • •

We are the picture people. I kept hearing the phrase in my head, repeating as I walked through Allison Katz’s show at Camden Art Centre, taking in her big, bright canvases, with their wild proliferation of images that repeat and echo and morph, surprise and enthral across twenty-four paintings, most of them made in the last eighteen months. Cabbages, cocks (the barnyard variety), mouths, self-portraits, eggs, openings, spaces within spaces, images within images, exhibitions within exhibitions—things overlaid, overlapping, contained, framed, staged. Katz’s subjects are vivid and energetic, unruly yet precise, as is her style and technique—the texture and tenor of which shifts subtly in each painting, attuned to whatever is at hand.

Allison Katz: Artery, installation view. Courtesy Camden Art Centre. Photo: Rob Harris. Pictured: Allison Katz, The Cockfather, 2021. Oil, acrylic, and rice on linen, 55 1/8 × 59 1/16 inches.

We are the picture people, the earworm persisted. It was only on the train home, brain still buzzing with Katz’s colors, punning titles (The Cockfather!), implied associations, rhyming shapes and forms, that I realized where the statement was from. In Lynne Tillman’s Men and Apparitions, her narrator—an academic ethnographer named Zeke—collects photos of families and the familial, including pets, blurred figures, empty interiors, sometimes snapped accidentally: the weird, hovering familiars of daily life that linger and accumulate, and from which we piece together versions of ourselves, our pasts and presents. “I name us Picture People,” he says, “because most special and obvious about the species is, our kind lives on and for pictures, lives as and for images, our species takes pictures, makes pix, thinks in pix. It exists if it’s a picture and can be pictured. Surface is depth, when nothing is superficial.” Katz’s métier is painting, not photography, but she too is a collector of images, an assembler of very specific scenes and tableaux: a maker of pix gathered from the materials and experiences of the everyday, though twisted, off-kilter, made strange and fantastic and perplexing, as if to say—avowedly, plainly, amorously—no, life just does not add up, and what of it? And as such, what can a canvas hold? Can a work of art be at once contradictory and coherent?

Allison Katz: Artery, installation view. Courtesy Camden Art Centre. Photo: Rob Harris. Pictured: Allison Katz, Elevator III, 2021. Oil on canvas.

Katz is keenly attuned to spatial encounters with her work and the specific temporality of any exhibition. The first piece in the show is Elevator III (2021), an open-doored lift rendered at one-to-one scale, hung on a wall on the other side of which, outside in the stairwell, is the gallery elevator. A ghost interior? An X-ray painting, allowing us to see right past the wall? The artist as escape-artist, this her fictional way out? Hyperrealist, it’s almost a joke, daring you to enter it, daring you to believe just how much a painting could simulate reality, daring you to answer your urge to reach out and press the buttons, summoning the sound of the metal doors as they slide shut behind you, that faint metallic smell. Around the corner are two rectangular images of legs erotically intertwined, a mass of feminine limbs that create sinuous and angular forms, though we cannot see from whom they issue. 2020 (Ephemeral) hangs above 2020 (Femoral) (both 2021): the former is painted in shades of dusky blues lit with luminous whites, its surface made rough and granular with sand; the latter in pale greens and grays, the canvas smooth. Both are interrupted by two large ovals (textures reversed: white and smooth in Ephemeral, black and rough in Femoral). The shapes appear like eyes or voids or portals in the pieces, nostrils or mouths, or the gaping and duplicated zeros—00—of 2020, that year of so much blank time and space. Ephemeral femoral, eggs and legs, with rhyme but no reason, in paintings holes are still painted—they can only pretend at transparency.

Allison Katz: Artery, installation view. Courtesy Camden Art Centre. Photo: Rob Harris. Pictured, top: Allison Katz, 2020 (Ephemeral), 2021. Pictured, bottom: Allison Katz, 2020 (Femoral), 2021.

“It may not look that way,” says Katz in a 2015 interview in Border Crossings, “but what I make is always connected to my life, like diary or notebook entries. So everything, including the obtaining of an image, is generated from an experience.” At the same time, she has also said that she is attracted to the way images “can communicate a surplus of meaning”—how they can portray or name without defining or confining, instead creating a chain of questions and ambiguities from which the viewer creates new meanings. The personal is a starting point, is porous, is always multiplying to take in other people, places, things. Katz herself appears across the exhibition in ways both direct and oblique.

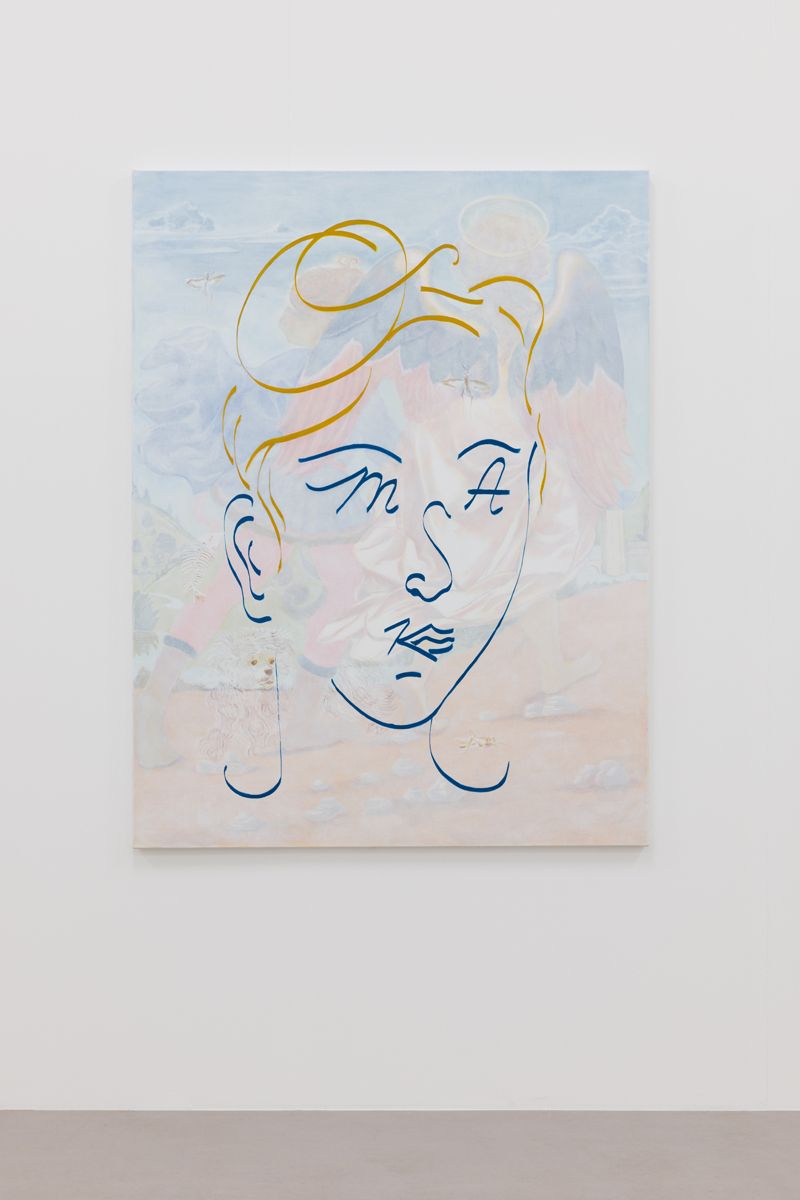

Allison Katz: Artery, installation view. Courtesy Camden Art Centre. Photo: Rob Harris. Pictured: Allison Katz, Akgraph (Tobias + Angel), 2021.

In Akgraph (Tobias + Angel) (2021), her visage, formed by her initials—MASK (Ms. Allison Sarah Katz)—in spare, cartoonish lines, floats over a version of Verrocchio’s Tobias and the Angel (1470–75), as though seen from behind, and through a pale veil. Katz was drawn to the Renaissance work that hangs in the National Gallery via affinity with “Tobias,” her mother’s maiden name. In Posterchild (2021), which is based on an interwar London Underground advertisement for Hampstead, details of the artist’s paintings, posters, and family photographs (childhood home, baby nephew) are outlined in black and superimposed against a background of trees and a cloud-streaked sky. One of the quoted images prefigures another self-portrait in the next room. M.A.S.K. (2021) is a painted version of the 2021 Spring/Summer Miu Miu ad campaign in which Katz featured, the slick fashion photograph realistically rendered in simple, flattened brushstrokes, but as seen from the inside of a giant mouth that acts as a toothy, undulating frame. Another mouth (the form references André Derain’s 1943 woodcut illustrations of Rabelais’s Pantagruel), whose teeth are painted in thin washes of mauve and lilac, surrounds a glass-like cat illuminated blue and streaked with purple tendrils: Alley Cat (2020), one of Katz’s nicknames.

Allison Katz: Artery, installation view. Courtesy Camden Art Centre. Photo: Rob Harris. Pictured, right: Allison Katz, Alley Cat, 2020.

Yet another mouth contains two grisaille mouths kissing; another, a brightly colored ceramic rooster; another, a 2016–17 William Copley exhibition at Fondazione Prada—an interior view of an interior view. The mouths hunger, they both consume and project images, they paint from the gut, so to speak, they hint at taste good and bad, they open wide, and I have the urge to pry them wider, to enter the cavity, to see more—as if the images contain something beyond themselves; and, in a sense, they do. On the backs of the five freestanding walls on which the mouth paintings hang are five small works in alcoves, all titled Cabbage (and Philip). Each shows a different variety of cabbage—pointed, Chinese, savoy—tenderly painted alongside the shadowy profile of Katz’s partner, Philip, in a Magritte-like composition.

Allison Katz: Artery, installation view. Courtesy Camden Art Centre. Photo: Rob Harris.

“To expose oneself is to go beyond the personal, and participate in the real of communal thought,” says Katz in a 2020 conversation with artist and editor Camilla Wills. “One must risk ‘using one’s own face,’ so to speak, in order to get behind it.” The artist has referred to the four edges of her canvases as entrances and exits. One can go into the work, but the work can also leave itself, travel out into the exhibition and beyond, as blood through an artery: life is inside art, and vice versa, and subjectivity is a vast and varied terrain. Camden Art Centre’s exhibition brochure contains a short reading list compiled by the artist, which features Annie Ernaux’s The Years, the French writer’s extraordinary, almost subjectless autobiography. “All the images will disappear” is its opening line. Yes, the Picture People might think, only to be made again, made new, the same but different, always ongoing.

Emily LaBarge is a writer based in London. She has written for Artforum, Bookforum, the White Review, Granta, and the Paris Review, among other publications. She is the London correspondent for the Montreal-based quarterly esse arts + opinions.