Quinn Latimer

Quinn Latimer

In search of immunity: a collection of writings by the novelist and artist.

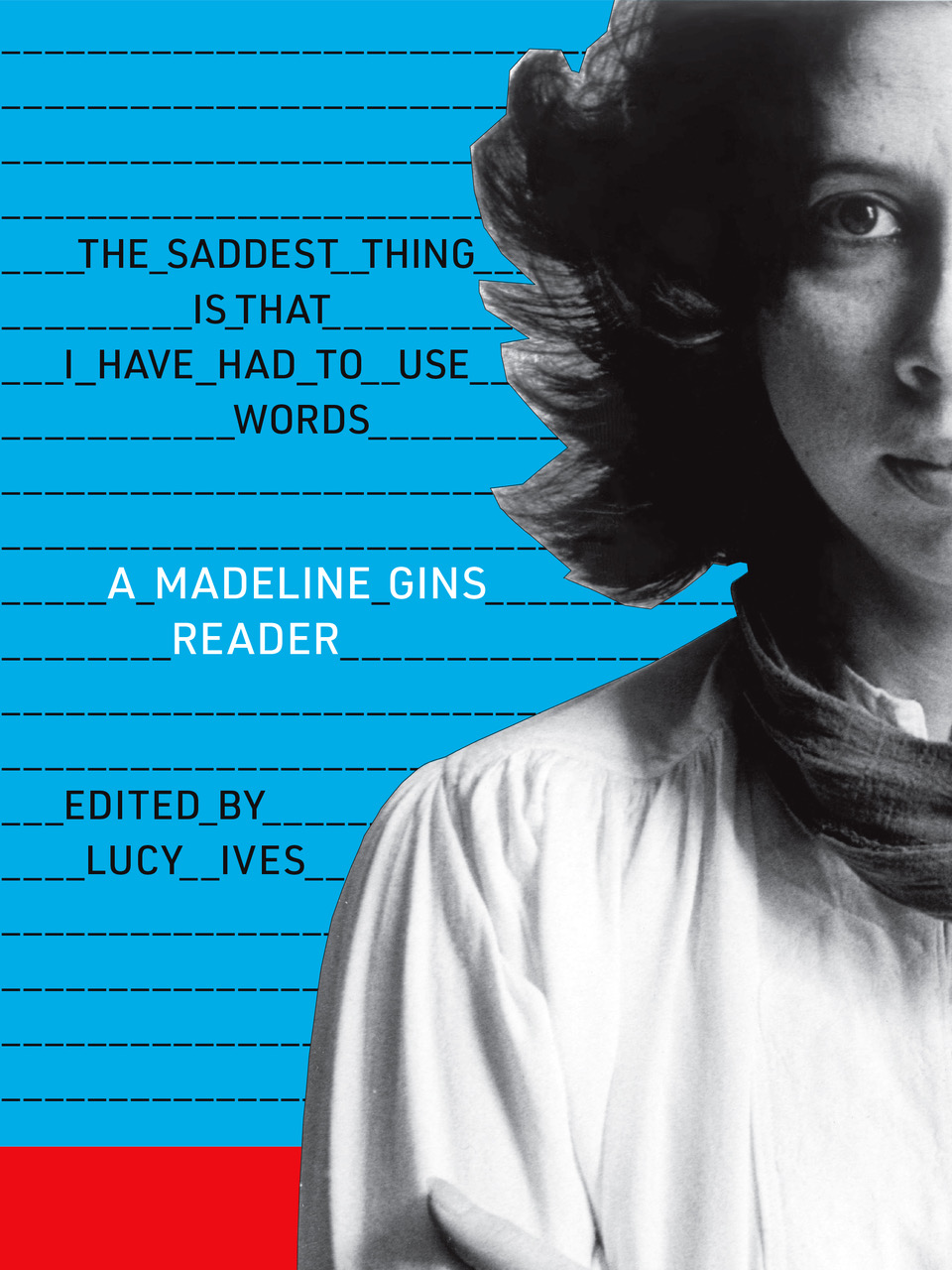

The Saddest Thing Is That I Have Had to Use Words: A Madeline Gins Reader, by Madeline Gins, edited by Lucy Ives, Siglio, 327 pages, $28

• • •

As I began reading Madeline Gins earlier this year—before epidemic became pandemic, before my city and I were quarantined in a sprawling grid of pale apartment blocks, before the bodies of the world were sequestered to their attendant architectures—I kept thinking back to a recent interview with Chilean poet and artist Cecilia Vicuña. Asked whether she thought our species deserved to continue, Vicuña answered, succinctly: “Not really.” Her admission kept blooming in my mind, a kind of welt. I could feel it there, as I brought my fingers to my forehead, then quickly brought them away, remembering: Don’t touch your face.

The questions of species continuation and the domestic architectonics in which such species as ours might best carry on are what Madeline Gins is, for various reasons, best known. An extraordinary experimental novelist and conceptual artist, poet and trained philosopher, Gins was also a speculative architect who, with her husband Shusaku Arakawa, attempted architectural environments that would stave off human death. Their Reversible Destiny project includes Bioscleave House (Lifespan Extending Villa) (2008), a home in East Hampton, New York, with vivid walls and wavelike floors. “This is a means to strengthen the immune system,” Gins notes sharply, in a documentary. “It has to do with not being so damn sure of yourself . . . you’re obliged to watch your balance, carefully.”

Watching one’s balance, carefully, is also what she obliges of her reader. The Saddest Thing Is That I Have Had to Use Words: A Madeline Gins Reader, a startling collection of essays, novels, artist books, and poems, edited by Lucy Ives, makes clear that Gins didn’t go for rote lyrical (or anti-lyrical) celebrations of language or comforting social narratives, but had more pressing goals. Employing a language equal parts phenomenology and microbiology, domestic-architectural intimacy and linguistic voracity, Gins’s literary ambition was nothing short of immunity.

Immunity from what, though? A possible list: from the tyranny of base and false language of political authorities; from the “microphytic agents” that might enter the writer/reader at every turn; from the veneers of meaning that surface words, which to Gins are not only sign, sound, and symbol, but mist, breath, substance, season, measure, odor, numeral, chemical, signal, gender, endlessly escaping material—that is, constantly transforming, or not. “The trial of the imagination ends in the sentencing of words,” she writes, judiciously, judge and patient both.

Born in the Bronx in 1941, and raised on Long Island, Gins writes with an environmental foresight and formal virtuosity that can feel prophetic. Her texts—even with their midcentury cadences and wry urbanity, their suburban pathos and ludic conceptualism; Gertrude Stein seems the mothership, here—describe the perceiving reader/writer body’s interface with its environment as a kind of lungs, in which each thing, every particle, is taken in and breathed back out. Strange, then, how this writer-architect celebrated for attempting to design immortality magnifies in her writing the molecular moment, the myriadly coded present in all its tactility, puzzles of smell, and many small moves: reading, writing, eating, waiting, scratching, breathing. In a world tilted toward future gains, to futures in every sense, Gins’s literary oeuvre feels deeply anchored in the extant and its most proximate locales of isolation and communion.

WORD RAIN (or A Discursive Introduction to the Intimate Philosophical Investigations of G,R,E,T,A, G,A,R,B,O, It Says), Gins’s 1969 opus, opens with a floor plan of an apartment. From here the novel proceeds, with the writer-protagonist reading a manuscript in the study as it rains outside. The writer’s isolation (like the word’s isolation) is relative: a partner invariably arrives to deliver sandwiches, a children’s party sounds from a nearby room. There is also the narrative within the manuscript itself, with its social scenes and the architectures that define them.

In one poignant crossed-out section (Gins is conscious of showing the stumbling motion of writing), a suburban scene of cinematic-midcentury import is slowed down like a film. Thus, all its elements—imagistic, civic, empathic—might be perceived. In a neighborhood of identical homes, a couple watch from a window as a husband chases his wife from their house onto the street. She jumps into a waiting car just as her husband reaches the road. He stands there, his wife’s shoes in one hand, a small steak knife in the other. Witnesses (readers) of this scene, the spectator couple “bounced with empathy on their neighborhood anxiety trampolines.” Platforms—for language and its attendant temporal orders—of all sorts are important to Gins. Rostrums, desks, papers, the word “platform”: all recur as both word and idea. Indeed, Gins repeatedly describes and performs the stage of writing, and of reading, which to her are an inviolable system. “Time is a platform (cf: this book),” she writes.

The Saddest Thing collects dazzling early essays like “The Fictions of My Non-Fiction” (ca. 1960s) and selections from What the President Will Say and Do!! (1984), a prescient portrait of Trumpian uppercase-exclamative nonsense, but I kept returning to WORD RAIN, with its mysterious adherence to the present, our interfaces and infectious agents. Its staging of the writer-reader, her mist (of language) matching the vapor (of rain) outside her windows, was wet with words: “breathing,” “perspiration,” “Hypnotic Vapor!” A kind of philosophy of breathing, of air (per Luce Irigaray, per so much Eastern thought). For Gins, these states of water are, irretrievably, language: “Words are water soluble. This is clearly and moistly so.”

Outside my room it was raining too. The rain was mixed with Sahara; my terrace had a wet, copper gleam. I wondered what Gins would make of this scene: how she’d parse these sands “of time” and place, their odor and chemical and meaning, both microbiological and macropolitical. What platform of neighborhood anxiety my terrace, wet and red, like all the terraces down the block, might imply and bounce—with the requisite anxiety (that steak knife, though)—into being. What I mean to say (to write) is this: I was inside, in quarantine—we all were, the whole street, the whole city, perhaps the whole continent—and it was raining. I was reading. “The gas mask reads in the mist,” Gins offered.

How odd to encounter such lines now, when the wetness of words, their aftermath, must be avoided (for we are not immune). How preternatural that their author believed architecture could breed immunity. Language too. “The lowed cackle / of the michrophytic agent / perspires the silence,” Gins writes in a poem. I thought about how for Gins language seems to only become real and readable when one breathes on some surface. Breath’s moisture, a mist of agents, allows language to exist, form to reveal itself. And what is language for? Communion and communication, yes, but what else? In “How to Breathe” (part of What the President Will Say and Do!!), Gins writes:

If you have not betrayed my confidence, you have not breathed yet. And what is breathing?? Whatever it is, let it continue where it may while you, for just a little while longer, continue to keep your distance.

Quinn Latimer is the author of, most recently, Like a Woman: Essays, Readings, Poems (Sternberg Press, 2017).