Quinn Latimer

Quinn Latimer

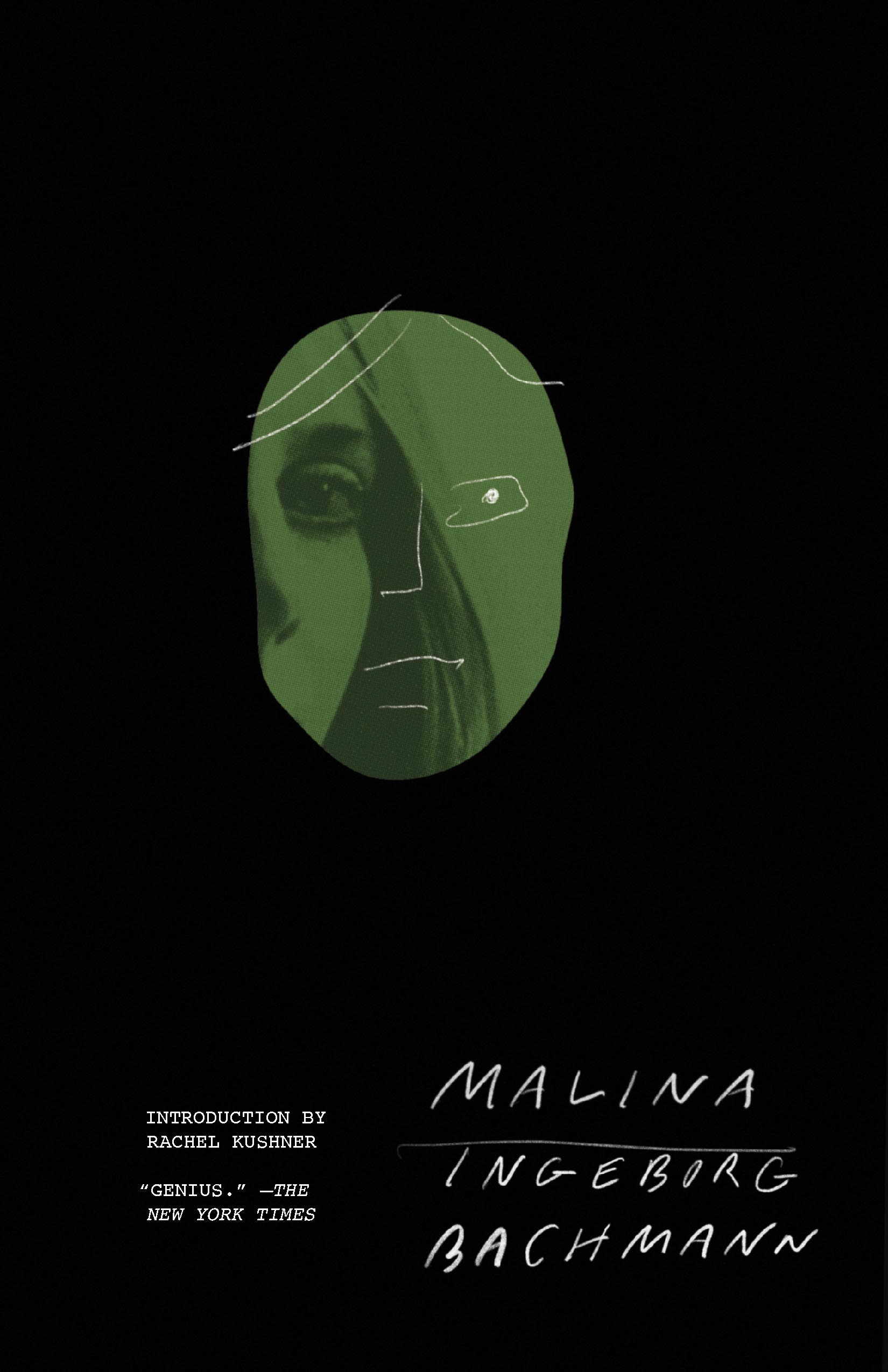

Terror and moral seriousness: New Directions reissues Ingeborg Bachmann’s 1971 novel.

Malina, by Ingeborg Bachmann, translated by Philip Boehm,

New Directions, 283 pages, $16.95

• • •

Malina is a man and Malina is a book. The only novel by Ingeborg Bachmann, the celebrated Austrian poet, published in 1971. In it, she writes: “Malina shall ask about everything.” But the man, Malina, does not. Not in the beginning. The narrator—an unnamed woman writer simply (not so simply) called “Myself” in the book’s cast notes—meets Malina at an interminable lecture on “Art in the Age of Technology.” They move in together in Vienna. She spends her days receiving and writing letters (signing them: “An unknown woman”) and carrying on an affair with a certain Ivan; Malina asks no questions. Malina is discreet or he is a ghost or he is a savior or he is a monster or he is a projection or he is part and parcel of “Myself”; this reader cannot tell. The narrator cannot tell either. She writes: “I must have known early on that he was destined to be my doom, that Malina’s place was already occupied by Malina even before he entered my life.”

Malina is an epistolary novel, in parts, also a kind of genre novel, in which pastoral interstitials suggest the parable. Both modes have a specific relationship to the margins of literature: epistolary novels were once for women, fairy tales for children. They also wear a particular moral armor and pedagogical terror: both center moral lessons and spiritual transformations. Bachmann’s moral seriousness, modernist and primeval, is nowhere in doubt, nor is her terror: it rides her language (burning and cooling, by turns) into strange dialectical valleys, up Alpine peaks, into labyrinthine Viennese apartments and sardonic lakeside villas. It strands the reader in transparent waters of time and place (some fairy-tale, primordial past; postwar Austria; a later economic miracle of technology and capital) but also in darker, wetter, more damaging questions of morality. Bachmann’s anxiety is moral, her clarity and lack of clarity moral, intimations of violence moral. These intimations within the novel concerning fascism’s roots in patriarchal violence are made explicit elsewhere by Bachmann, when she famously stated: “Fascism is the first thing in the relationship between a man and a woman.”

Certain books have an aura around them (we might use that term, attentive to its embarrassment). Malina does. Consider this reissue from New Directions, with a new introduction by Rachel Kushner; Malina will always be in style. This has as much to do with its writer as its (singular, preternatural) substance. Like her book’s double, Bachmann was born in Klagenfurt, in 1926. After a dissertation on Heidegger (though Wittgenstein would prove to be more influential on her writing), she achieved immediate, immeasurable fame as a poet, winning the Group 47 Prize in 1953 for Die gestundete Zeit. Her literary legacy as a central postwar European writer was compounded by gendered gossip and glamour: she was blonde, an addict, had affairs with Paul Celan, Max Frisch, and, it is conjectured, Henry Kissinger. She died in Rome from a fire (smoking in bed) in 1973. Malina was to be the first book in a series called Death Styles.

In Malina, those styles are specific, not general. In the second chapter—the novel is arranged like a triptych—the narrator finds herself in a cemetery of “murdered daughters,” her father’s hand digging into her shoulder. Then he traps her in a house, which turns into a gas chamber, where he tears her tongue out. In her hallucinations, her father disassembles into a pantheon of patriarchs: a priest, a Kaiser, a collaborator, a Nazi, an opera director, a film director, “the city’s number one couturier.” In each scene he wants to sleep with her, to kill her; he burns her books. She must sing for her supper but she has no voice. She wakes from these nightmares and Malina is there, taking care, inscrutable. She roams the book-heavy apartment they share; she falls back into sleep. She dreams, she writes. Is there a difference? She is a “dark tale,” she writes/dreams.

In one of her dreams, the narrator has a child. He needs a name; she suggests Animus. Carl Jung described the animus as the unconscious masculine side of a woman. Indeed, the child is a boy. Jung also had a famous case about a child who was “never really born”—a girl. Bachmann writes: “I feel he is nameless like the unborn.” This constant switching within gender—led forth by language and its naming—is indicative of Bachmann’s feminist-psychoanalytical concerns in Malina. Her narrator asks: “Am I a woman or something dimorphic? Am I not entirely female?”

What are names, what is language, what is female? “Feminist consciousness can be thought of as consciousness of the violence and power concealed under the languages of civility, happiness, and love,” the feminist scholar Sara Ahmed has written. Bachmann locates the unspoken terror of war and genocide’s aftermath in her double’s relations with the men who haunt her memories: the stranger who slapped her as a child; the father who did untold things. Ivan and Malina seem little better. “Ivan moves his hand menacingly, since I’ve said something dumb,” Bachmann writes. Even when they claim to care for her, the men in her life laugh at her fear, her anxiety, her writing, belittling that system of violence which they are part and parcel of, each in their own manner.

But Malina is also, at times, hilarious. The third, last chapter begins, as any good epistolary novel might: “At the moment my greatest fear may be the fate of our postal officials.” Bachmann goes on to observe, wryly: “Mail delivery in particular would seem to require a latent angst, a seismographic ability to receive emotional tremors.” Such humor quickly dissipates into a philosophical conversation on gender, spirit, and flesh between the narrator and Malina that suggests a Socratic dialogue (yet another literary genre that Bachmann deftly employs). This dialogue—and the book—ends when the narrator disappears into a crack in the wall, attended to by one of the finest last lines of late-twentieth-century European literature: “It was murder.”

There is something skinless about Bachmann’s writing, it has no cover. She is the one who has “forgotten to make a mask,” as her narrator states in despair, even as masks and alter egos—Malina, Ivan, the lean autofiction of “herself”—abound in her book. “I, too, go on living somewhere, blessed with all kinds of wounds,” she states. Who is she? Who is Malina? That is the question—maybe the same one. Despite Bachmann’s preoccupation with the relations between women and men and gendered violence, her concerns are not binary. Instead, it is a series of trios that populate this book: three chapters, three characters, one relationship among three people. “I need my double existence,” Bachmann confesses, “my Ivanlife and my Malinafield” (shades of Celan there; shades of The Tempest too: “Every third thought shall be my grave”). Linear time is equally unresolved. Bachmann’s narrator notes: “It’s not growing old that amazes me, but the idea of one unknown woman succeeding another unknown woman.” A certain Woolf wrote: “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.” Bachmann admits: “I never did solve the problem relating to time and space. Later it grew and grew.” It did; it does.

Quinn Latimer is the author of, most recently, Like a Woman: Essays, Readings, Poems (Sternberg Press, 2017).