Jo Livingstone

Jo Livingstone

Love thy irksome neighbor: the late Lauren Berlant’s final book.

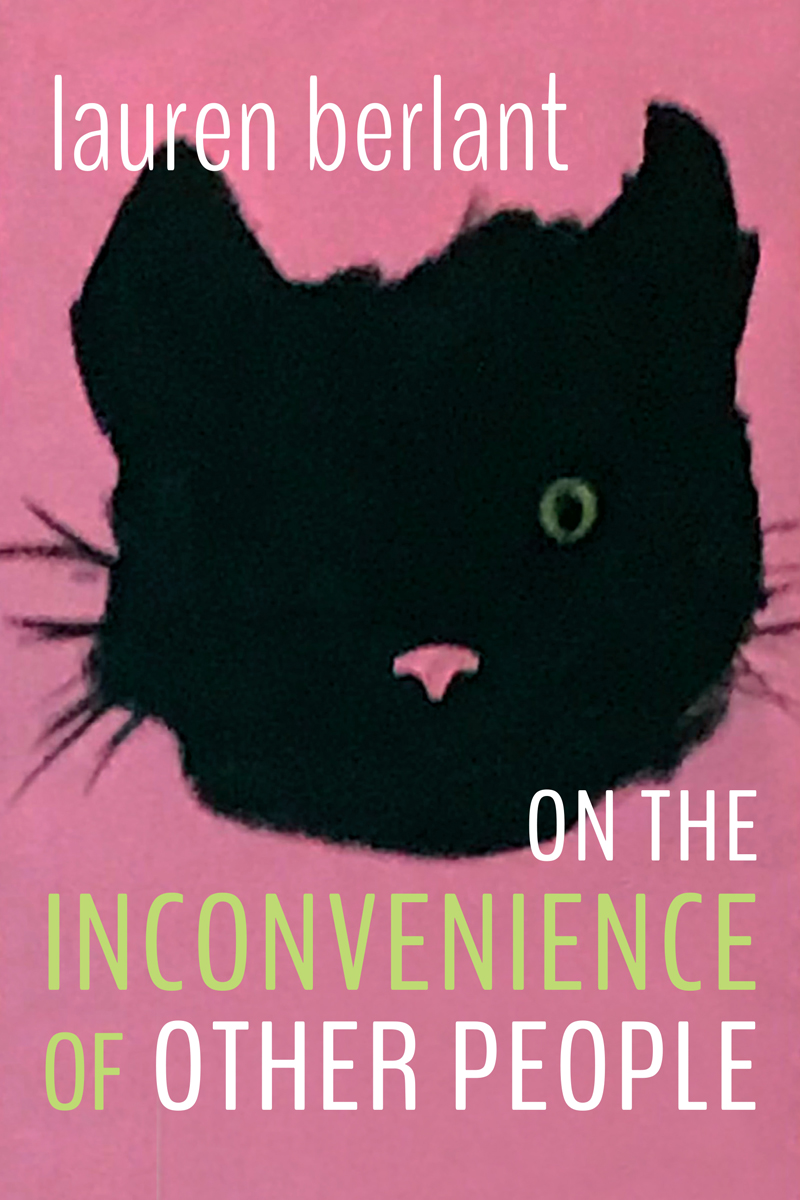

On the Inconvenience of Other People, by Lauren Berlant,

Duke University Press, 238 pages, $25.95

• • •

When University of Chicago professor and eminence in the field of affect theory Lauren Berlant passed away last year at the age of sixty-three, they had, like Columbo, just one more thing to say. Duke University Press is publishing On the Inconvenience of Other People posthumously, and it sports some unfinished-feeling parts toward the end. But on the whole, it is a coherent and helpful addition to the ideas, now influential throughout the culture, that Berlant wrought in 2011’s Cruel Optimism, and—despite being written in the torturous style affect theory is notorious for—it clarifies a few points.

Cruel Optimism is a detailed book, but its argument is concise: what we want hurts us. At one level, this is the most conventional of observations, a notion from a song lyric (the term “affect theory” always makes me hear Morris Albert’s “Feelings” in the distance). But Berlant means it in a political sense, and in the sense of a machine that can be taken apart in order to articulate its elements.

The most direct illustration in Cruel Optimism concerns what people used to call the American Dream. “The conditions of ordinary life in the contemporary world even of relative wealth, as in the United States,” they note, “are conditions of the attrition or the wearing out of the subject.” Writing on the brink of the Occupy movement’s transition into a major news story, their argument tied the daily fear of living through major recession to a form of irony. By dwelling on the ironic fact that “the labor of reproducing life in the contemporary world is also the activity of being worn out by it,” Berlant finds “specific implications for thinking about the ordinariness of suffering.” Constantly looking toward the future, when we will finally roll that rock all the way up that hill, we “suspend questions about the cruelty of the now.”

On the Inconvenience of Other People delves into the consequential implications of a seemingly glancing passage in Cruel Optimism in which Berlant transforms a local problem into a general principle through one massive, bravura sentence about neighbors:

In the American dream we see neighbors when we want to, when we’re puttering outside or perhaps in a restaurant, and in any case the pleasure they provide is in their relative distance, their being parallel to, without being inside of, the narrator’s “municipally” zoned property, where he hoards and enjoys his leisured pleasure, as though in a vineyard in the country, and where intrusions by the nosy neighbor, or superego, would interrupt his projections of happiness from the empire of the backyard.

The context is their analysis of a John Ashbery poem, but it’s a general idea. Neighbors are annoying, an intrusion into the perfection of bourgeois leisure, one which Berlant compares to a hypercritical superego.

Moving away from that city block–level situation, Berlant takes up the irksomeness of sharing space with other people as the full subject of their new study. Structured around three “assays” and a coda, On the Inconvenience of Other People is about exactly that, inconvenience, in the word’s most ordinary sense. Berlant—after a lot of throat-clearing, including acknowledgments that “this book might be irritating because of its insistence on the many both/ands of attachment,” so consider yourself forewarned—argues that the grating of our own lives against the lives of other people is the product of “an inconvenience drive—a drive to keep taking in and living with objects.”

It could be anything: the bus being full; the rat running out of my neighbor’s trash can and over my foot; the fact that having sex with a stranger is dangerous. These are other people exist problems. Berlant utilizes the discipline of proxemics, meaning the study of the relation of nearness between things, to read them. Being in inconvenient proximity to another person is not like being “acknowledged or known.” And yet it has everything to do with desire and compromise: “I want to be near you, but what does that entail in terms of need, demand, obligation, the ephemeral, the enduring, the event . . . ?”

Inconvenience is something like the opposite pole of attachment—and its eternal companion.

If attachment is “what draws you out into the world,” Berlant argues, “inconvenience is the adjustment from taking things in.” The theory is delightfully practical at the level of helping the reader forgive their own tendency to make their own life more complicated, the same way that Cruel Optimism was an invitation to forgive ourselves for being unemployed and depressed in 2011.

Because inconvenience is universal and inherently about improvisation and negotiation and difficulty, it “generates a pressure that is hard to manage, let alone bear,” Berlant writes. Everybody finds other people inconvenient, yet we are all also inconveniences to others, ad infinitum. This affect, or “situation,” as they also term it, is both “ordinary and profoundly life-shaping.” It’s “a description of a relation so foundational to coexistence that it’s easy to think of it as the whatever of living together and not a constantly pulsing captivation of response.”

The “inconvenience drive” helps explain, for example, the reason so many people want to live in big cities, not just despite but because of the difficulties. It is considered chic and environmentally minded these days to live in quasi-homesteading isolation, rearing chickens and contemplating geological time. But most of us live in cities, at some level by choice, and we choose the inconvenience and the humanity of trading goods for money. There’s a lot of bad writing about the allure of living in or leaving New York, London, or Paris, but that genre’s propensity toward romanticization and oversimplification makes Berlant’s super-dense style feel precise and surgical by comparison.

On the Inconvenience of Other People refines Cruel Optimism by adding detail, which is what Cruel Optimism did for Morris Albert’s “Feelings.” There is a fractal aspect to affect theory, in terms of the size and indeterminacy of its object, because the human situations its practitioners analyze are intuitively familiar to all of us. That’s the point, but it still feels disorienting and warping to read. Articulating a paradoxical relation is difficult, especially when, as in Berlant’s book, the task involves trying to isolate aspects of everyday life to show that they have tiny internal mechanics: it’s like keyhole surgery, or performing an autopsy on a bee. Fiddly, but cool.

Jo Livingstone is a critic based in New York.