Jeremy Lybarger

Jeremy Lybarger

Dennis Cooper returns to a personal obsession in a metaphysical wheel of a novel.

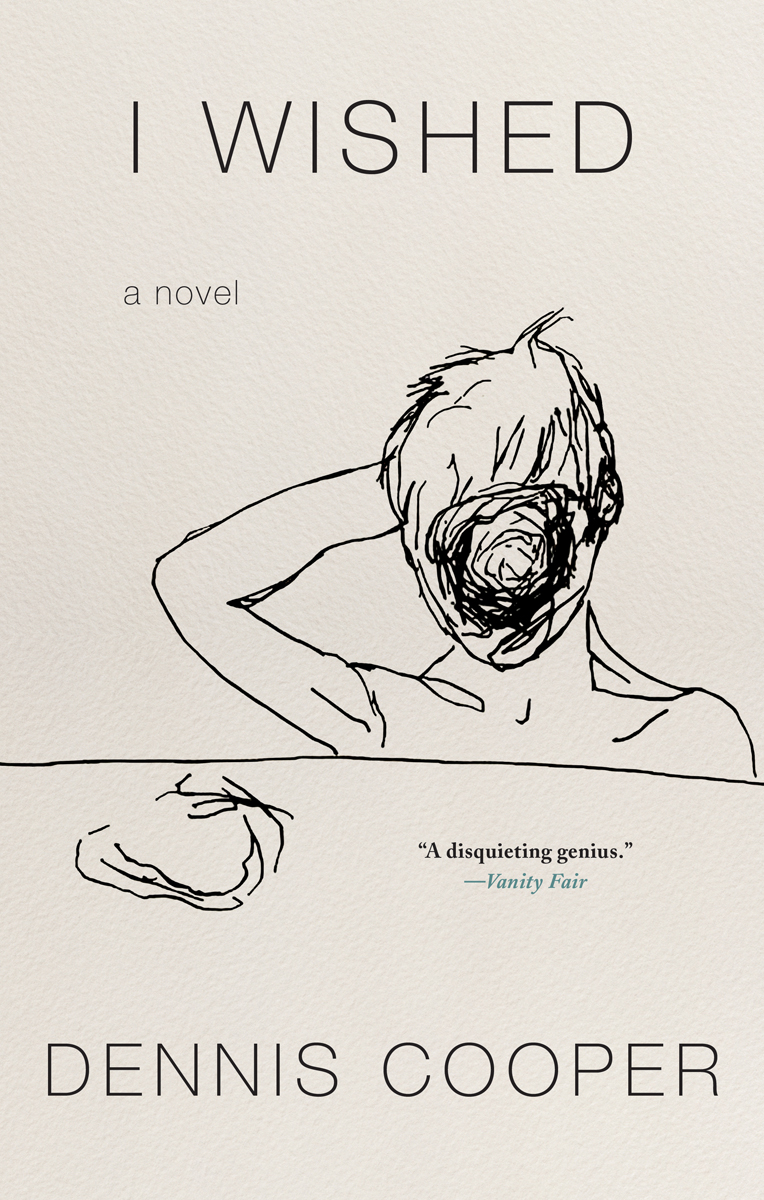

I Wished, by Dennis Cooper, Soho Press, 127 pages, $25

• • •

Between 1989 and 2000, Dennis Cooper published a quintet of novels known as the George Miles Cycle, named after a childhood friend—and later lover and muse—whom Cooper has described as the most important person he’s ever known. Miles was a tragic figure. Diagnosed as manic depressive at age fourteen, he drifted on and off medications, attempted suicide, was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, and eventually decamped to a fundamentalist Christian commune. Cooper, meanwhile, moved abroad to become a writer. He sent Miles letters that largely went unanswered. In 1987, on his thirtieth birthday, Miles shot himself in his childhood bedroom. Cooper didn’t learn of the death for another ten years.

The cycle—Closer (1989), Frisk (1991), Try (1994), Guide (1997), and Period (2000)—memorializes Cooper’s intense, stunted obsession with Miles while also reconfiguring its namesake as an ensemble of teenaged boys who share a numb vulnerability. The protagonists of these novels are fumbling and inarticulate, eddying through spasms of nearly catatonic sex and violence that Cooper renders with forensic neutrality. Although the books were intended as tributes to Miles, they’re so jagged and oblique, so angular in style, that Miles feels more like a residue beneath these texts than a fully embodied character—a psychic stain that has never lifted.

I Wished, Cooper’s beguiling new novel, resurrects Miles once again. This time the artifice of fiction is ventilated with memoiristic candor. “I want this book to be more public than my others,” Cooper writes, going on to suggest that former classmates and family members will read it and come forward with their memories of the real George Miles. And, yet, almost immediately the book subverts its fact-finding mission. The first full chapter, titled “Torn from Something,” opens with Miles’s father having just killed his wife; he then begins to masturbate the twelve-year-old Miles while making the boy confess his sexual fantasies. This version of the character recalls the Miles of Closer, whose mother also died, albeit in a hospital. (The real-life Mrs. Miles of Southern California was never murdered.) The rest of the chapter sketches a recursive précis of Miles’s life, but the timeline is all warped. At one point Miles talks to a boy online, although chat rooms were scarce in the 1970s or ’80s, when this episode ostensibly takes place. Here one is reminded of Cooper’s The Sluts (2004), a decoupage of invented emails, websites, and posts from gay male escorts that add up to an evasive metafiction. The title “Torn from Something” is perhaps a winking hint that the something in question is Cooper’s own previous work. As I Wished progresses, the narrative subterfuge of its first half gradually coalesces into a knotty memory book that’s less about Miles the person and more about Miles the talisman that unlocks Cooper’s artistic compulsions.

Those fixations—sadomasochism, death, language—are familiar to Cooper devotees, but here they’re fragmented across a character study that’s self-referential and intertextual. Instead of pursuing a plot arc or the cathartic rollout of a memoir, I Wished interleaves shifting tones, as evidenced by Cooper’s subjects, many of which gesture to childhood or adolescence: Santa Claus; the singer Nick Drake, a patron saint of young angst; the serial killer John Wayne Gacy, who preyed on teen boys; and the twink twins on the short-lived TV western The Monroes. One chapter concerns The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, whose main characters—two “deaf-mutes,” one of them institutionalized—roughly parallel Cooper and Miles. In the Carson McCullers novel (and its 1968 film adaptation, which Cooper references), the character John Singer serves as caretaker and confidant to a quartet of disenchanted locals. In I Wished, Cooper toggles between roles, casting himself as both Singer and McCullers: a doomed guardian on one hand and a would-be artist on the other. I say would-be because Cooper acknowledges that he’s never found a form “magnificent enough” to actualize his own version of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, the “sacrificial gift” that he’s long wanted—and tried, and failed—to write for Miles.

Is I Wished that book? According to Wrong (2020), Diarmuid Hester’s biography of Cooper, the novelist attempted to write a memoir of Miles in 2012 but shelved the idea. In I Wished, Cooper, or his narrative doppelgänger, notes that he spent seven months writing down everything he could remember about Miles, as “honestly and artlessly” as he could. If I Wished is the result of that exorcism, the “magnificent” form Cooper finally settled on is simultaneously concentric and telescopic, a metaphysical wheel that spindles across time while always orbiting the question of whether Cooper’s love for Miles was ever requited. The answer to that riddle will intrigue Cooper’s longtime readers more than newcomers to his work, for whom the Miles of I Wished won’t have the totemic allure of the Miles of the quintet or the decades’ worth of interviews around it. I Wished is a soberer and more conceptual addition to that mythos. For readers not already seduced by the Miles of the cycle, the new novel’s style will likely fog any deeper understanding of him as a flesh-and-blood person. That’s to be expected. Muses are indecipherable by nature.

I Wished accretes through callbacks and repeated motifs of holes, wounds, and disability. A chapter titled “The Crater,” midway through the book, personifies Roden Crater, James Turrell’s large-scale artwork in the Painted Desert region of Arizona. For nearly a half century, Turrell has bulldozed and bored here, installing tunnels and apertures and antechambers into this ancient volcanic cone whereby visitors can contemplate light. In I Wished, the crater is isolated and downbeat, anxious to be loved. “I worry I’m a frame. I worry I’m a decoration,” the crater says, perhaps speaking as a metaphor for Cooper’s grief. But the crater also signals the novel’s wormhole architecture, and, more pointedly, prefigures a chapter titled “I Wished,” in which Cooper recalls a childhood brush with death. When Cooper was ten, a friend accidentally split his head with an ax while they were playing in the yard. “I was squashed onto the ground,” he writes, “out cold and with a volcanic vent-like wound erupting in my budding hippie hair.” (We know this anecdote is true, or mostly so, because it also appears in Hester’s biography.) In a later chapter likewise titled “The Crater,” Cooper’s head wound and Turrell’s artwork converge in Miles, whose suicide Cooper vividly reenacts: “Blood is pouring from his mouth and nose. I was told that. There’s a crater in his head.”

The novel abounds in these internal echoes. For the reader the effect is occasionally disorienting, with the seemingly disconnected vignettes evoking the messy tectonics of memory itself. Here’s another echo: as a teenager, Cooper was obsessed with fifteen-year-old Robert Piest, Gacy’s last victim. Recounting Piest’s 1978 murder, Cooper writes that Gacy killed the boy and then stared, awestruck, at a light bulb in the ceiling. “Light,” Gacy muttered to himself—a gnomic eureka moment that may or may not be Cooper’s invention. That light illuminated something revelatory to Gacy, in the same way the light at Roden Crater reveals something to those who make the pilgrimage there, or the way in which Cooper sheds light on his departed friend in this novel and the novels before it. But the metaphor is shoddy. Light can just as easily obscure as delineate, as the fabled golden hue of Southern California, where Cooper and Miles grew up, attests. There’s a darkness in that knockoff paradise that some people never outrun.

Jeremy Lybarger is the features editor at the Poetry Foundation. He has written for the New Yorker, Art in America, the Paris Review, the Baffler, the Nation, and more.