Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

Jonathan Franzen heads back to the family.

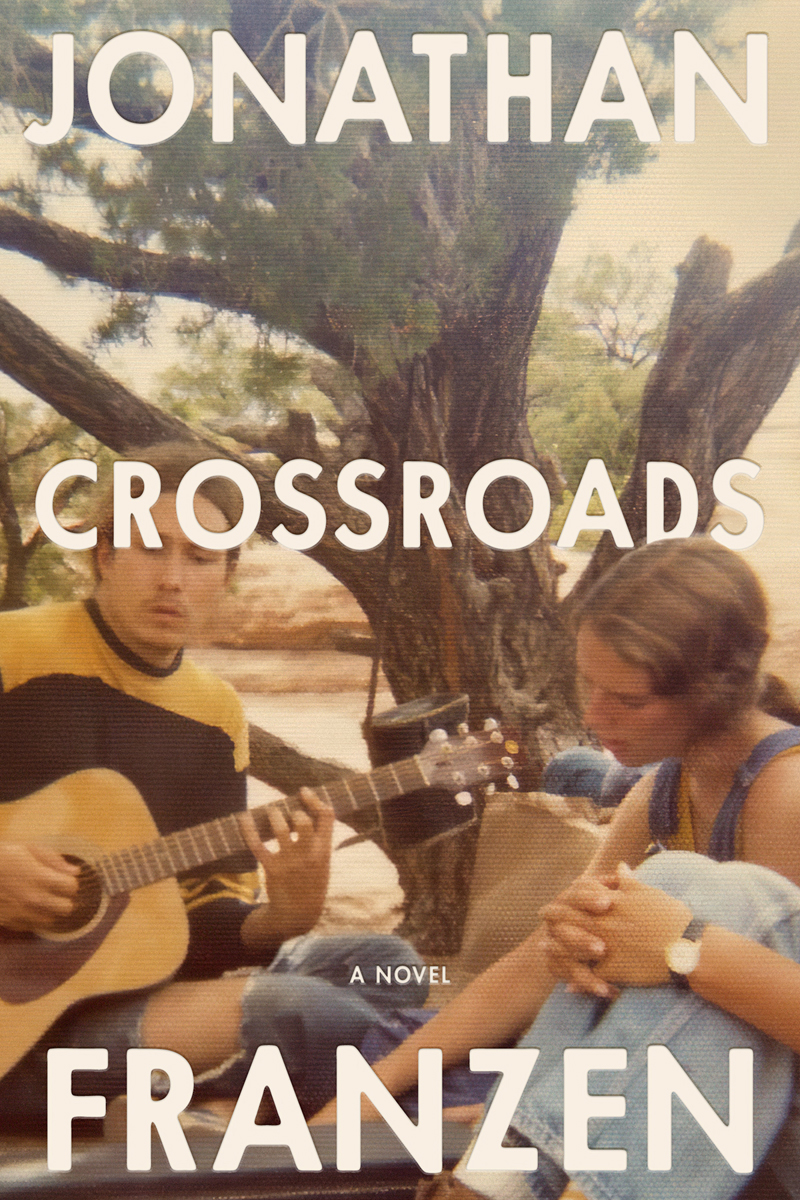

Crossroads, by Jonathan Franzen, Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

580 pages, $30

• • •

In April of 1996, Jonathan Franzen published “Perchance to Dream” in Harper’s, a bit of handwringing over the state of fiction that was republished, after Much Discourse and a round of meta-wringing, as “Why Bother?” in his 2002 essay collection How to Be Alone. Franzen wrote that “at the heart of my despair about the novel had been a conflict between my feeling that I should Address the Culture and Bring News to the Mainstream, and my desire to write about the things closest to me, to lose myself in the characters and locales I loved.”

Franzen went on to admit that his anguish was partly just rhetorical cardio on the path to clarity: “As soon as I jettisoned my perceived obligation to the chimerical mainstream, my third book began to move again” (emphasis mine). That book was The Corrections, a novel so good you can only play yourself by rejecting it (and which became—wait for it—mainstream entertainment). The “Perchance to Dream” essay turned out to be less concerned with defining The Novel and more about Franzen choosing where to direct his energy, which was clearest in his exchange with linguist Shirley Brice Heath. After conducting her own interviews with fiction readers, Franzen relays in his essay, Heath reported their saying that “what religion and good fiction have in common is that the answers aren’t there, there isn’t closure.” Heath’s conclusion is that what readers “hang on to” is a “sense of having company in this great human enterprise, in the continuity, in the persistence, of the great conflicts.”

His latest book, Crossroads, is Franzen’s best novel because he has stuck to his beloved “characters and locales” and kept both Culture and News in the picture without stapling them to the family portrait from outside. The continuity Heath speaks of is there when we look to Franzen’s families, who rise up through the twentieth-century novels (The 27th City, 1988, and Strong Motion, 1992, both beholden to a “systems” view of insidious corporate behavior more felicitously rendered in David Foster Wallace’s brief “Mister Squishy” story) and find a home with the Lamberts of The Corrections. The Hildebrandt family of Crossroads offers Franzen a wealth of continuity; so much of it that the novel, set in the early 1970s, is the first volume of A Key to All Mythologies, a trilogy that will follow the Hildebrandts up to the present. Crossroads gives us the feeling that Franzen takes the project of keeping us company in the human enterprise very seriously.

In the summer of 2001, right before The Corrections was released, Donald Antrim interviewed Franzen for BOMB. “The most important experience of my life, really, to date, is the experience of growing up in the Midwest with the particular parents I had,” Franzen said. “I feel as if they couldn’t fully speak for themselves.” Russ and Marion Hildebrandt are the parents Franzen can now speak for, unhappy in a way that does not feel specific to the suburbs near Chicago but does feel native to Franzen’s continuous families: they have a coiled horniness and an endless frustration with the project of being good. Russ is a pastor at First Reformed, where he is locked in a cold war with the younger Rick Ambrose, the “director of youth programming” who starts Crossroads, an unusually popular youth group. Falling somewhere between AA and EST, Crossroads practices a blend of confrontation and confession that ends up drawing in two of Russ’s kids, the effortlessly popular Becky and the analytic, twisted Perry, her younger brother. (Both parents and three of the four Hildebrandt kids get their own chapters, but little Judson, only nine, will have to wait for the rest of the trilogy.)

Russ is nuts for Frances Cottrell, a young widow in his congregation, while Marion is drifting back toward a memory: Bradley Grant, a car salesman she slept with decades before in LA. All Frances has to do is wear a plaid wool hunting cap for Russ to find her “gut-punchingly, faith-testingly, androgynously adorable.” Franzen told Antrim that he writes about sex “partly because I feel like it’s something I can write well about and I seldom see written about well,” which is almost accurate. What Franzen renders so vividly is desire, especially when thwarted. The Horny White Twentieth Century is in better hands with Franzen than those Agitated East Coast Fellas.

The struggle here really is more about doing “the right thing,” a phrase that pops in the dialogue of almost every character. The Hildebrandts all skirt a modified Calvinist line, suggesting that attempts to plead with God are pointless, though they can’t help wondering if they just haven’t found the right wording. Perry constantly second-guesses himself, whether he’s trying to stop selling drugs or start taking them again. Becky doesn’t know if she finds God through her James Taylor–ish boyfriend Tanner Evans or weed or through actual grace. These distinctions matter, deeply, to the Hildebrandts, and Franzen manages to make these emotional challenges as tense as the infidelities and intramural squabbling.

Marion, given a fairly rough road here, comes very close to delivering the Franzen cheat code when speaking to Sofia, a therapist nobody in her family knows she is seeing. After telling Sofia how “selfish all human love is” and “how bad all people are,” Marion announces that “the only love you can be sure isn’t selfish is loving God, which isn’t much of a consolation prize, but it’s all we’ve really got.”

I neither like nor dislike any of these characters but cared desperately about what was happening to all of them. They are whole, entire people, and, like them, this book feels whole, fused, and seamless. What will allow the continuity through two more volumes is that Crossroads finds a throughline in God as a problem, not God as solution—the dialogue is not prescriptive. Whether or not Marion believes her goodness is illusory, the love that she and her kids all chase is either family itself or its inverse. (Nobody sleepwalks through Crossroads—everyone keeps making a bet on something.) That somebody wants now, in a moment overtaken by facts and their abrogation, to discuss goodness? I’ll walk with the Hildebrandts.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York.