Jeremy Lybarger

Jeremy Lybarger

A debut novel explores the suburbia of our discontent.

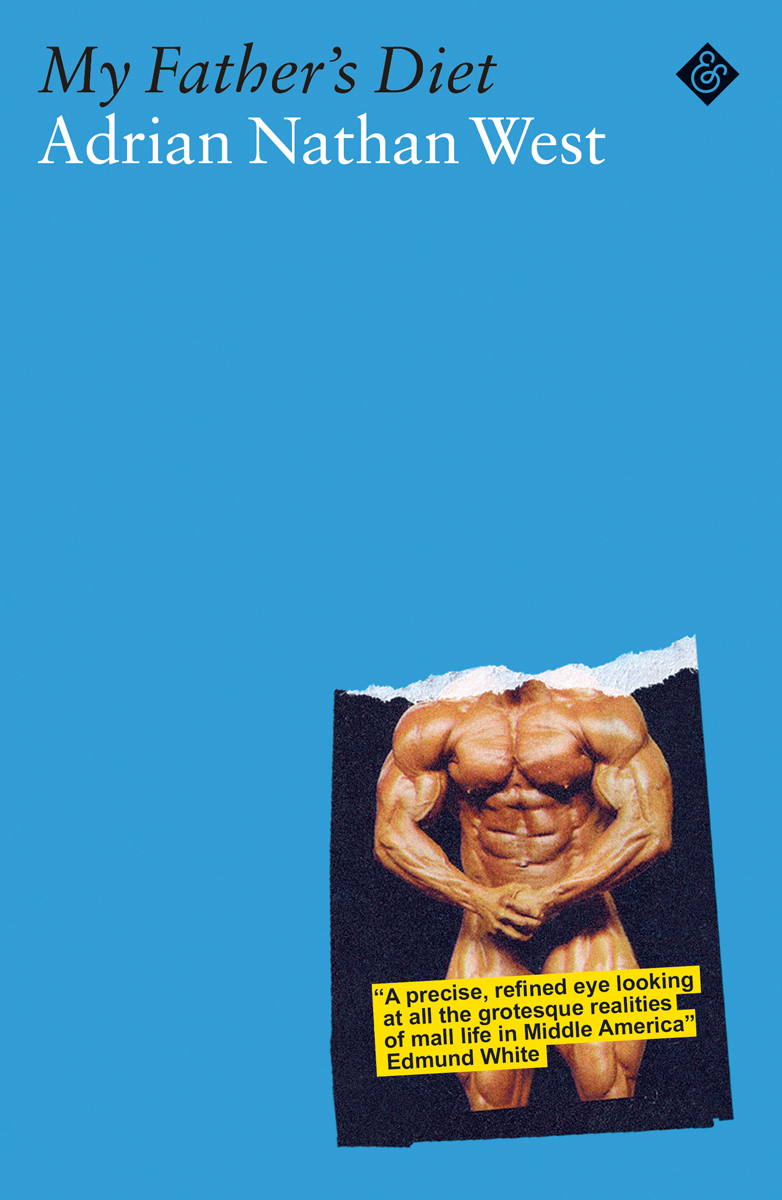

My Father’s Diet, by Adrian Nathan West, And Other Stories,

173 pages, $16.95

• • •

Mr. America 1963—otherwise known as Vern Weaver—waged a masochistic crusade in the weight rooms and cellars of southern Pennsylvania. Barely out of high school, his ambition was to be a top bodybuilder, but his treasonous muscles wouldn’t bulk up. After losing the national title twice, he later reflected, “My life was a total wreck. I had no place in life because I had forgotten what I really wanted out of life.” What he wanted was what generations of Americans before and since have coveted: a centerfold physique that insinuates discipline and self-mastery, a cellular regimen of exceptionalism and brute willpower that reflects the national spirit. Weaver pumped iron until he finally clinched the title at age twenty-six. Thirty years later, he shot himself.

My Father’s Diet, the debut novel of critic and translator Adrian Nathan West, shares some of the mordant pathos of Weaver’s story. The unnamed narrator is a hyper-observant college boy who witnesses his father’s midlife crisis—although, in this book, everyone eddies in a whirlpool of simmering discontent. After an ugly divorce and the failure of the holistic health center he helped bankroll, the father (also unnamed) abruptly enters the Body You Choose competition, a twelve-week fitness contest sponsored by the Total Body Development Corporation. “I have my coffee in the morning, a drink sometimes in the afternoon, read the paper, read my stuff for work, and the whole time, I’m just thinking, is this it, is this all there is? What’s the point of my life on this planet?” the father asks, rationalizing, if not entirely explaining, his salvational embrace of amateur bodybuilding.

This impromptu quest is typical of the novel’s characters, many of whom are slouching toward a higher calling—or at least killing time. The narrator studies French in hopes of one day becoming “a person of culture.” His mother and her new boyfriend (dubbed the Weirdo) buy a dilapidated house in the country, “gripped by the notion of the freedom it would supposedly bring them.” The father’s second wife, Karen, is a self-taught mindfulness guru who opens a natural healing center in her backwater town. (She grew up in Namibia, thanks to her father’s job, and still spends her downtime listening to recordings of tribal drums.) Even some of the walk-on characters are enterprising apparitions; the narrator meets a man on the bus who composes “urban greeting cards . . . like Hallmark . . . but real-life stuff.” As the would-be poet pulls out a sheaf of samples, the narrator clocks “neat rows of horizontal scars” on the man’s arms. Deep sadness and an entrepreneurial instinct coexist like a call and response.

All of this jockeying is set against a backdrop of manufactured banality: strip malls, housing developments, archipelagos of fast-food franchises and retail superstores ringed by freeways. When the narrator joins his father and stepmother on a holiday road trip to Kansas City before the divorce, he’s initially charmed by the hardwood forests along their route. But his father informs him that the trees were planted to prevent erosion, and that he recalls fishing in a nearby man-made lake as a kid. This anti-romanticism quells the novel’s few other concessions to nature. On that same trip, the family makes a stopover at a campground, where the father is spritzed by a skunk. Elsewhere, the narrator chugs a bottle of cough syrup and meanders by a “landscaped lake” on his college campus, gauzed in a pharmaceutical stupor that’s not much different from his sober state, when he listens to familiar music on a loop and rewatches old movies, as if nuzzling comfort animals. The father’s house, meanwhile, is in a woodland cul-de-sac fronted by a billboard proclaiming Development Opportunity!

The United States is a country whose architecture—recent, modular, noncommittal—reifies a deeper psychic rootlessness. West picks up on this idea when describing a motel “that paired the lowest architectural standards with the elaborate and pointless conceit of a turreted tower clad in cultured stone.” The narrator, almost erogenously sensitive to environmental pretensions and affectations, finds in the tawdriness around him an existential angst. Driving through a low-rent retail corridor plastered with clearance ads, he notes the “uniform looks of despair” on the faces of the bored employees inside. Where other authors might opt for satire, West instead delivers a kind of highly wrought kitsch realism that implicates everyone, including the narrator. His style’s mingled tenderness and grotesquerie can sometimes read like a distant cousin to Winesburg, Ohio. “I wanted to get out of town, out of my clothes, out of my marriage, out of my body, out of everything,” says Elizabeth Willard, the failed actress in Sherwood Anderson’s bleak chronicle of small-town life. The narrator of My Father’s Diet, at a chain restaurant with his father, laments that “everything on the menu was fried or smothered with cheese, and this frying and smothering and lathering, all those oleaginous descriptors with which the very glossy illustrated menu induced one to try what was, in the light of reason, a horrifying array of confections . . . already contained, in miniature, some essential aspect of the life I believed I wished to escape.”

That escape is impossible doesn’t make the attempt any less obligatory. Early on, Karen gives the narrator a book titled Are You Here? A Guide to Practical Mindfulness, a mash-up of New Age spiritualism and pop psychology. West expertly mimics the milky tone and half-baked insights of self-help literature: “When a memory arises, let it flow away. When anxiety about the future strikes, just say: That is not me. You are the thing that is here and now.” The irony is that the narrator—or any other character—should strive to be more present in a culture that’s undeniably numb and insipid. As if to underscore this point, the novel is ambient with infomercials, court TV shows, and tabloids; there are references to pyramid schemes, suicide, and families peddling their prescription drugs. We know the setting is 1998 because the news features a report about the Connecticut lottery killings, in which a disgruntled employee shot four coworkers at the state lottery headquarters. There are also allusions to the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal and to the TV series The Pretender. Being mindful in America, West suggests, is not to invite wisdom, but to cultivate a boredom that turns even the nation’s lunacy into something as rote as weather.

The father’s physical transformation occurs more than halfway through the narrative, when readers are already mired in the disappointments and inertia of West’s world. True to the ethos of kitsch realism, the Body You Choose competition isn’t played for laughs but is the kind of beefcake pageant whose very earnestness is laughable. The competition distills all of the novel’s other themes, particularly the idea that changing your body, your attitude, or your surroundings will somehow change your life. Americans’ faith in self-reinvention—a faith that is now itself a commodity—is the final punchline. “I guess I always had the idea that at some point everything would be perfect, that my job would be settled, my home, my love life, and then I’d have time for the rest, but it doesn’t seem to ever happen that way,” the father muses near the end. He’s right. Even Mr. America can’t have it all.

Jeremy Lybarger is the features editor at the Poetry Foundation. He has written for the New Yorker, Art in America, the Paris Review, the Baffler, the Nation, and more.