Blair McClendon

Blair McClendon

A retrospective revisits the films of the great American director.

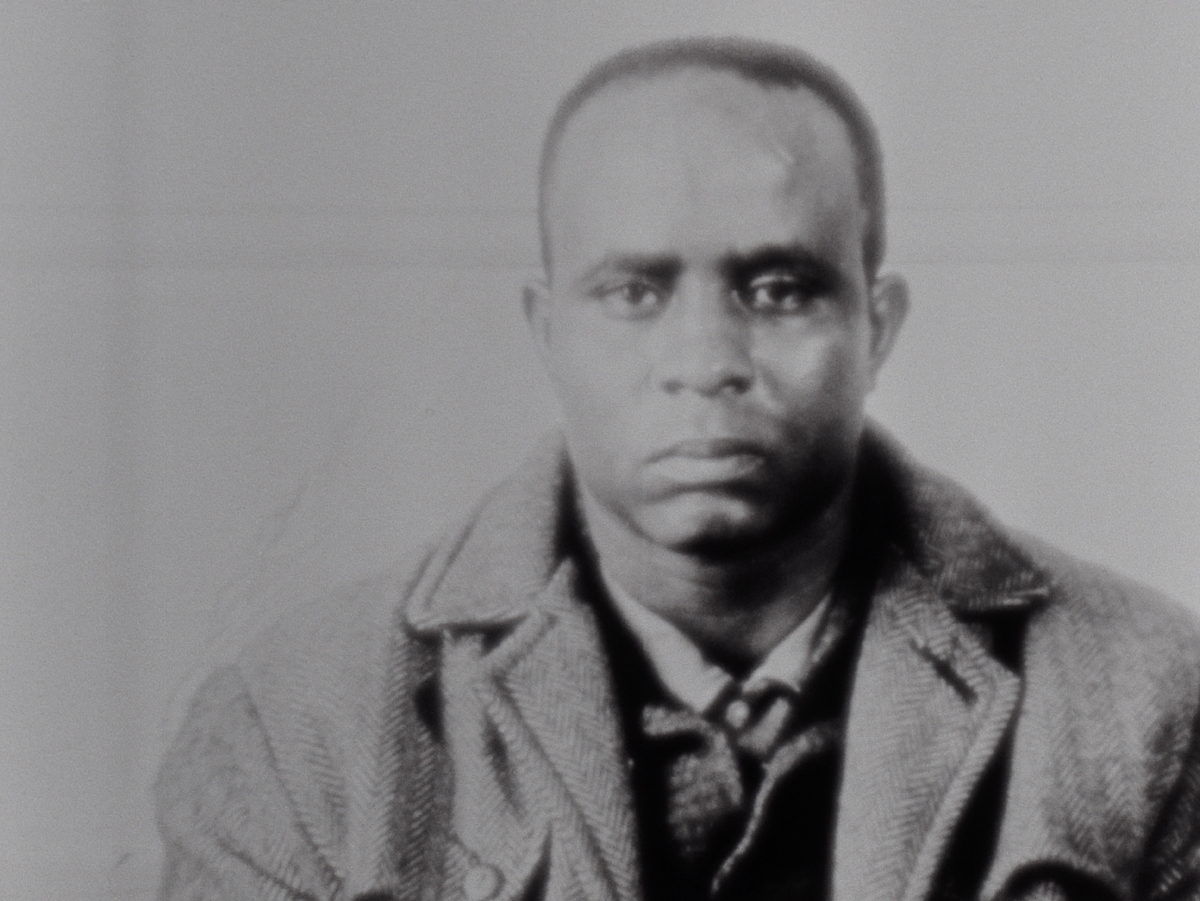

Gordon Parks filming Leadbelly, circa 1975. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation.

“The World of Gordon Parks,” now playing at Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, New York City, through December 11, 2021

• • •

There are those whose work so altered the world that our memory of their time on earth is hopelessly intertwined with their art. Gordon Parks (1912–2006) is one of these artists. He is most popularly remembered for photographing the effects of what W. E. B. Du Bois termed “the color line.” His Alabama photographs have become nearly synonymous with the public memory of segregation, but his polymathic brilliance looms large over any number of arenas. It is hard to look at, say, Cate Blanchett in Todd Haynes’s Carol, set in the early 1950s, without also seeing Parks’s late ’40s photographs of model Barbara Wood in a muskrat coat and glowing with wealth and elegance.

In addition to the photographs, there were novels, music, and movies. Anthology Film Archives’ “The World of Gordon Parks” series focuses on the latter and includes a fiftieth-anniversary screening of the landmark blockbuster action film Shaft (1971). The American system is not known for taking great care of its film artists, even the commercially successfully ones. Still, by 1976, Parks was able to embark on the biopic Leadbelly, his true passion project. The gorgeously shot film unfolds slowly, less concerned with a digestible thesis than explorations of the stories and legends surrounding the eponymous blues singer. But Paramount executives were chasing the last buck. Instead of opening the world up to him, the success of Shaft constrained Parks. It had, along with Melvin Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song (1971), birthed the blaxploitation genre. But where their creators saw cocksure heroes countering the “Uncle Tom” characters, as Parks put it, of American cinema, studios saw sex, violence, and a new market to exploit.

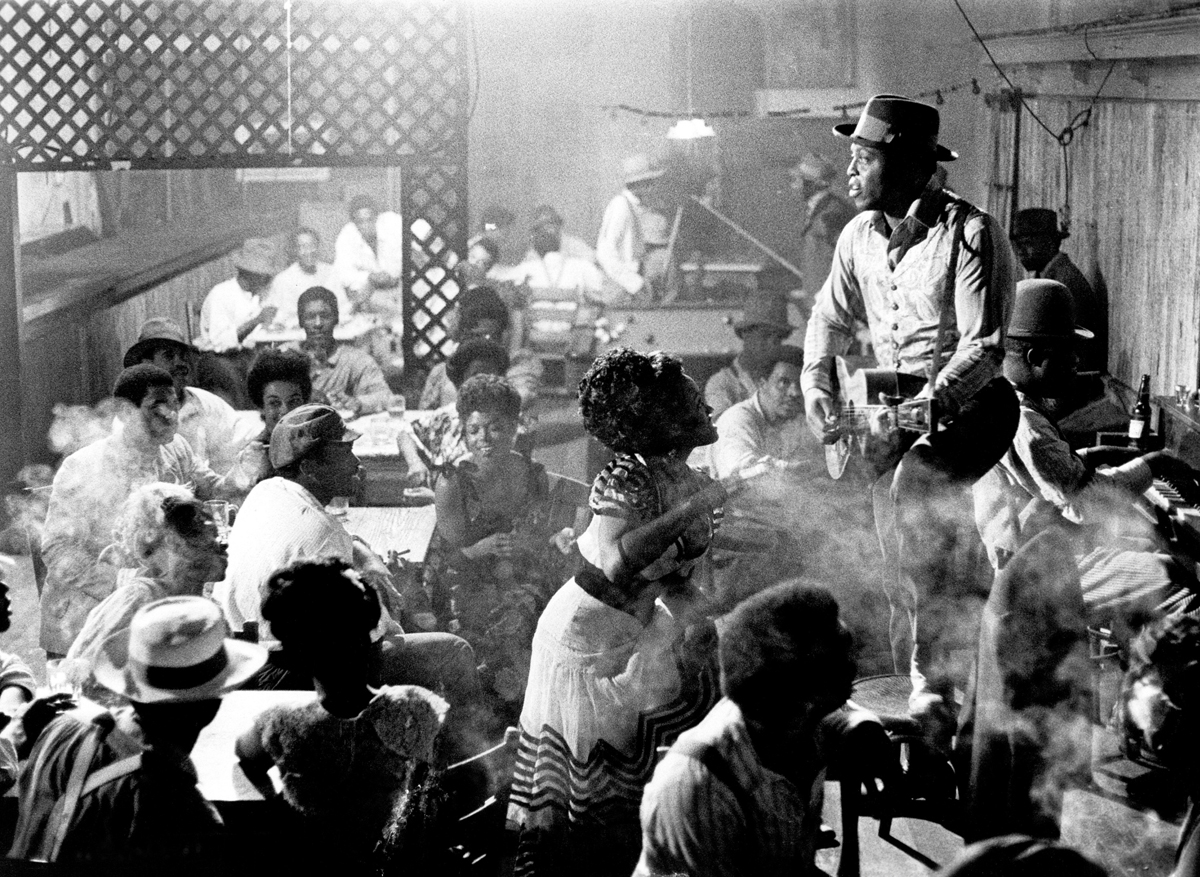

Roger E. Mosley (on stage) as Leadbelly in Leadbelly. Courtesy Paramount Pictures / Photofest. © Paramount Pictures.

The first ads for Leadbelly showed the singer, played by Roger E. Mosley, half naked, looking off into the distance, and emphasized his criminal record. For Parks, it was tantamount to sabotage. In an interview with the Detroit Free Press, he described the shame of having “already given up quarts of blood trying to get them to throw the [ads] out.” He told journalist Barbara Kevles that when the film was set to open in Washington, the studio hadn’t even told the local critics. Parks continued his fight, but eventually settled on differing ad copy “for different audiences.” The problem, as Paramount saw it, was that black viewers had “a profoundly emotional experience,” whereas “white audiences were more interested in the music and one ad can’t cater to both audiences.”

Roger E. Mosley (far right) as Leadbelly in Leadbelly. Courtesy Paramount Pictures / Photofest. © Paramount Pictures.

It was probably the truth, but a bitter one to hear when concerning a film like Leadbelly. About halfway through it, Leadbelly and fellow bluesman Blind Lemon Jefferson (Art Evans) find themselves performing at an all-white hootenanny in a hall decorated with a portrait of George Washington and a Confederate battle flag. It’s two in the morning when the musicians decide to call it a night. The drunken party organizer insists they keep playing, even though the agreement was to stop at midnight. The singer bends down to pick up his guitar, stooping so low that he is eye to eye with the good old boy. The organizer smiles and turns to the crowd, satisfied by his own authority. Leadbelly finds his own satisfaction by breaking the guitar across the smug man’s back. It is a miracle that he is only beaten and imprisoned.

A question runs throughout most of Parks’s films: What is the best way for black people to live under and to fight against white supremacy? Parks rightfully framed this as an internal debate. In Solomon Northup’s Odyssey (1984), a PBS movie based on the same autobiography that inspired Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (2013), it is staged through a series of confrontations between the free-born Northup and those who were born into slavery. In Shaft’s Big Score!, the 1972 follow-up to Shaft, the infamous private detective tells an inquisitive local cop that his recently murdered friend warned him to “stay away from black honkies with big flat feet.”

Richard Roundtree as John Shaft in Shaft. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

In spite of the ways that Parks’s status as the “black first” par excellence smoothed out his legacy—his debut feature, the semiautobiographical The Learning Tree (1969), was the first to be directed by a black American for a major studio—he never mistook the necessity of black unity for evidence of the thing itself. The pressure that history applied to black Americans was too great and felt too dissimilarly to expect a united front. Some of his characters, like the diffident youth at the center of The Learning Tree, focused on education, and others, like Shaft, rode as close to the third rail as possible. But there was always room in Parks’s films for those whose response to the outrages of American life was plain rage. When prison guards cage Leadbelly in a steel sweatbox, a fellow inmate advises him, “You suit your ways to the situation. Some other time you can chonk that white man on his head. But now you just study on living till tomorrow.” Living is enough in a country that wants you dead. He offers the singer a meager meal, which Leadbelly knocks back against his face. Better, for him, to die unbroken.

Diary of a Harlem Family. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

While the features are the centerpiece of the Anthology retrospective, the short documentary Diary of a Harlem Family (1968) most effectively distills Parks’s practice. The film, which expands on some of his Life photographs, opens with a riveting close-up of the father of the Fontenelle family. Parks sits beside him, narrating the man’s position in life. For all the contemporary talk about documentarians working with their subjects, few are as willing as Parks was to actually frame the stories in their presence. After the camera has pushed all the way into Mr. Fontenelle’s face, it then pans and reveals the whole family. Zooms and pans pick apart photographs of this Harlem household, highlighting the gestures meant to represent a way of life. The documentary closes with Parks’s words, describing a riot yet to come. He says, “As we crossed the streets and climbed the four flights to the cold apartment, I could only wonder why they waited for summer.”

Diary of a Harlem Family. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

The hot summers would come again and again, but one doubts that many people could hear what he was saying. The edition of Life from March 8, 1968, showed a Parks photograph of a teary-eyed black child with the title “The Negro and the Cities: The Cry That Will Be Heard.” Just over a month later, Parks was tasked with writing Life’s essay on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination. A photo caption described Vice President Humphrey as “expressing the nation’s sorrow” to Coretta Scott King. Parks, on the same page, asked, “In spite of the tears in Ebenezer and all over the country, how moved, really moved, was the white conscience?” If it wasn’t clear that the question was rhetorical, he continued, “Believe this, no matter what anyone else tells you: you have pushed us to the precipice.”

It would be too simple to say that Parks is relevant again because we are back at that precipice. Parks is relevant because his work is excellent, because the image of twentieth-century America cannot be thought of without him, and because we are not back at all. We never left the edge where Parks’s films reside. They are sometimes light and laughing, sometimes bitter and furious, but always they have one eye peering over into oblivion, beckoning us to come and see, before we fall.

Blair McClendon is an editor, filmmaker, and writer. His film work has screened at Sundance, Cannes, Tribeca, TIFF, and other festivals around the world. His writing has been published in n+1, the New Republic, the New York Times Magazine, and elsewhere. He lives in New York.