Julie Phillips

Julie Phillips

“S is for Susan who perished of fits”: Mark Dery offers the first major biography of Edward Gorey.

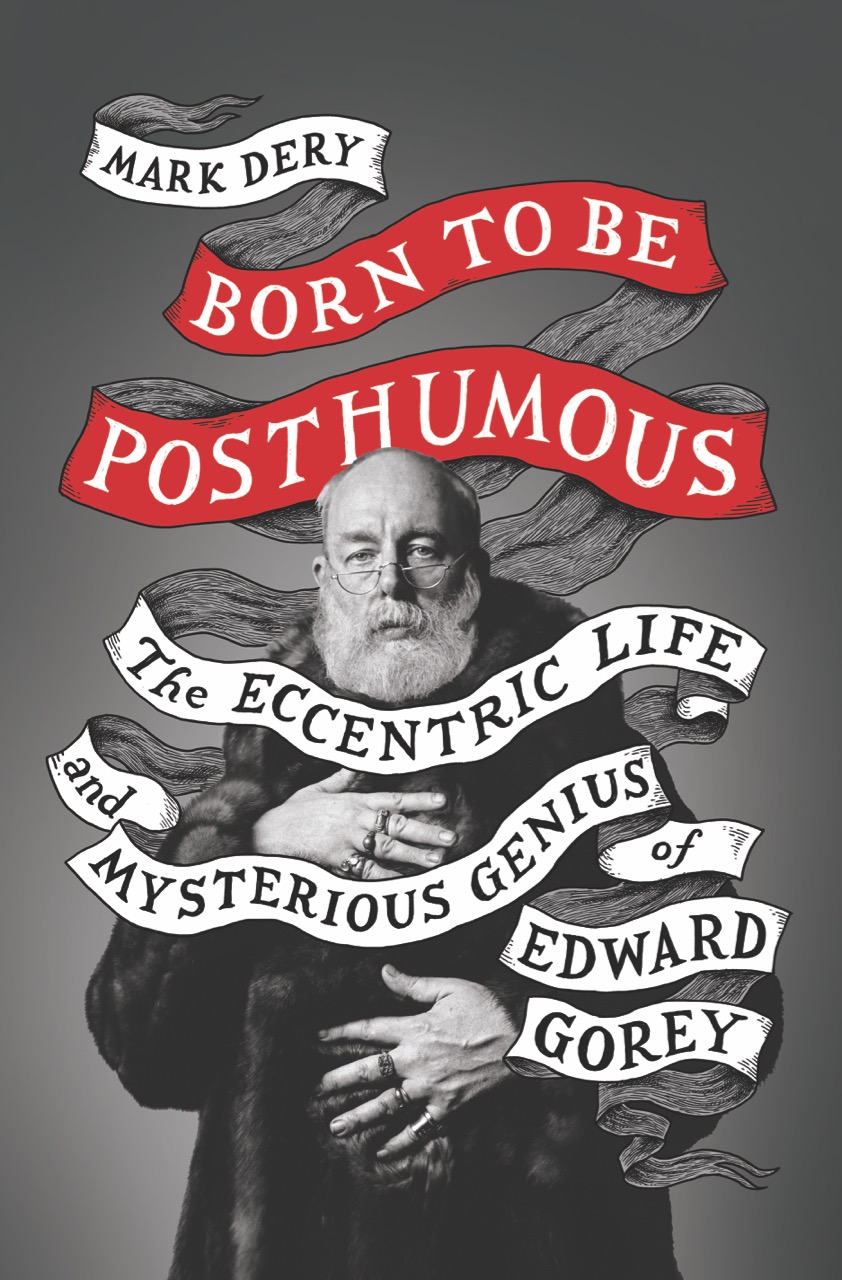

Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey, by Mark Dery, Little, Brown, 503 pages, $35

• • •

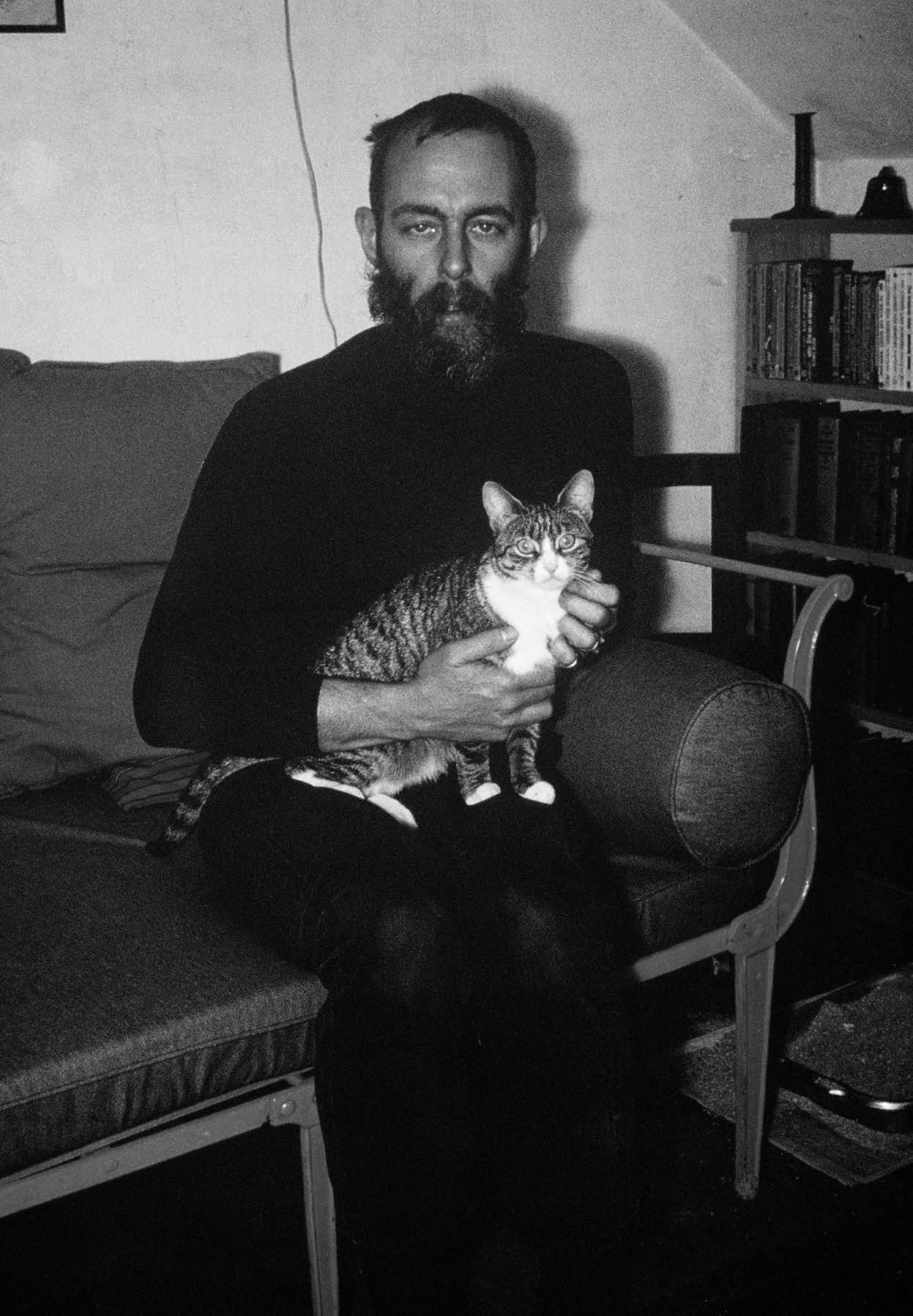

By his mid-twenties, the artist and illustrator Edward Gorey had already settled on his signature look: long fur coat, jeans, canvas high-tops, rings on all his fingers, and the full beard of a Victorian intellectual. His enigmatic illustrations of equally fur-coated and Firbankian men in parlors, long-skirted women, and hollow-eyed, doomed children (in The Gashlycrumb Tinies, among other works) share his own gothic camp aesthetic. Among the obvious questions for a reader of Gorey’s biography are: Where in his psyche, or in the culture, did all those fey fainting ladies and ironic dead tots come from? And, not unrelatedly: Was Gorey gay?

This last question has no easy answer. But it’s one that his biographer, culture critic Mark Dery, comes back to in interesting ways throughout Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey, the first major look at his life and career. If you had to guess at a sexual identity for Ted Gorey, it might be “solitary.” Though he had many friends, his Harvard classmate John Ashbery remembered him as “somehow unable and/or unwilling to engage in a very close friendship with anyone.” In his twenties, he described to the novelist Alison Lurie his visits to gay bars in New York and told her wistfully that he probably “ought to be having a few direct emotional experiences, however small.” But then he fell in love with men who didn’t love him back and had his heart broken. So he retreated to his overfull studio apartment on East Thirty-Eighth Street in New York, a place Dery calls his “cabinet of wonders, bohemian atelier, and Fortress of Solitude rolled into one.”

Edward Gorey, 1961. Photo: Eleanor Garvey.

Gorey described himself as “undersexed” in a 1980 interview, and equivocated: “I’ve never said that I was gay and I’ve never said that I wasn’t. A lot of people would say that I wasn’t because I never do anything about it.” Did he reject a gay sexuality, or was his particular sexuality, perhaps asexuality, not yet on the menu? Dery isn’t out to judge, and encourages us instead to look at how Gorey’s arch imagery, flamboyant self-presentation, and “pantheon of canonically gay tastes” (ballet, Marlene Dietrich records, silent film) allow him to be read in the context of gay culture and history, whatever his praxis in bed.

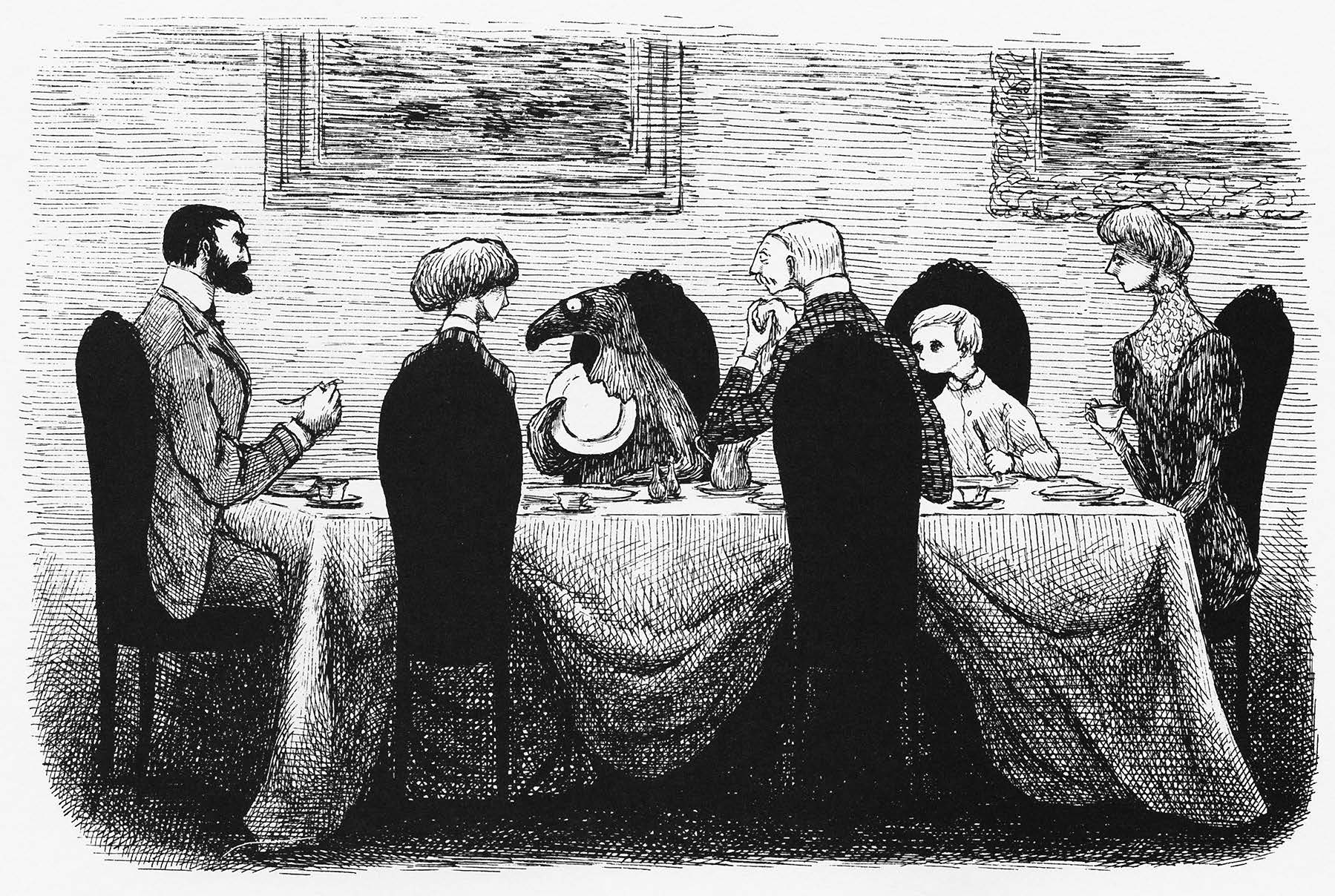

The chapbooks that he wrote and drew from the 1950s to his death in 2000—volumes “the size of a Pop-Tart,” in Dery’s words, with titles like The Doubtful Guest and The Curious Sofa—appealed to bright, maladjusted readers of all kinds, especially after they were made widely available in the collection Amphigorey. Darkly shaded, eruditely silly, his drawings confronted the bland optimism of midcentury America with illogic and unhappy endings. Life was too miserable for happy silliness, Gorey once said, so “if you’re doing nonsense it has to be rather awful, because [otherwise] there’d be no point.”

Edward Gorey, “It joined them at breakfast and presently ate / All the syrup and toast, and a part of the plate,” from The Doubtful Guest, Doubleday, 1957.

Which is not to say that he wasn’t fun to be around. When he worked as a designer and illustrator at Anchor Books in the 1950s, a colleague recalls, he had a gift for expressing the office id. “If you were on a project and you were stuck, and the editor was just unbearable, and you hated the assignment but you had to get it done, you’d say, ‘Ted, throw me a tantrum.’ For three or four minutes, he would jump up and down and scream. All the tension went out of the art department.”

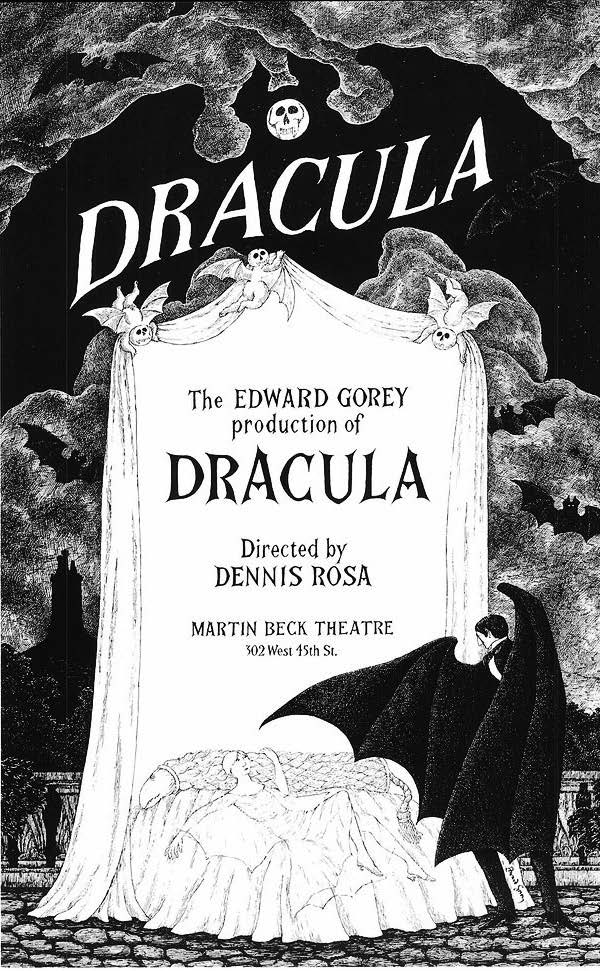

Gorey was born in 1925 and grew up in Chicago, with money on his mother’s side and infidelity on his father’s. He was a precocious and voracious reader whose writing would later draw on his childhood consumption of the works of Hugo and Dickens, true crime, and a vast quantity of English murder mysteries. Agatha Christie was his “favorite author in all the world,” he often claimed (though he said the same of Jane Austen). He had that love of ghost and vampire stories peculiar to readers who feel themselves to be the haunted house or the monster.

Edward Gorey, poster for the Broadway revival of Dracula, 1978.

At Harvard he studied French and worked on his persona, together with his new poet friend Frank O’Hara. At a time when the prevailing masculinity was all swagger and bluster, Gorey, O’Hara, Ashbery, and their contemporaries were pulling together clothes and reading lists to come up with a queer alternative. I wish Dery had included more on Gorey’s friends and more quotes from his correspondence, but he’s excellent on Gorey’s cultural influences and obsessions. These were wide-ranging, from George Balanchine’s New York City Ballet to Oulipo writers like Raymond Queneau, from surrealist philosophy to Japanese literature. He was “absolutely ga-ga” over The Tale of Genji and in a letter quoted a line from Lady Murasaki’s diary: “Yet the human heart is an invisible and dreadful being.”

The problem for Dery as a biographer is that nothing much changes in Gorey’s adult life. There are none of the usual romantic attachments and disasters, no dramatic failures, few changes of scene. He collected strange objects, read, and drew. And because part of Gorey’s protest against the conditions of his life is to refuse introspection, he is not entirely knowable, despite Dery’s best efforts. Even his seemingly intimate confessions are full of ironic exaggeration and deflation, like this one in a letter from the late ’60s: “Early or rather earlier in the day I was feeling madly euphoric with the absolutely splendid futility of everything, but now I am depressed, and want to have a good cry. Perhaps I am hungry.”

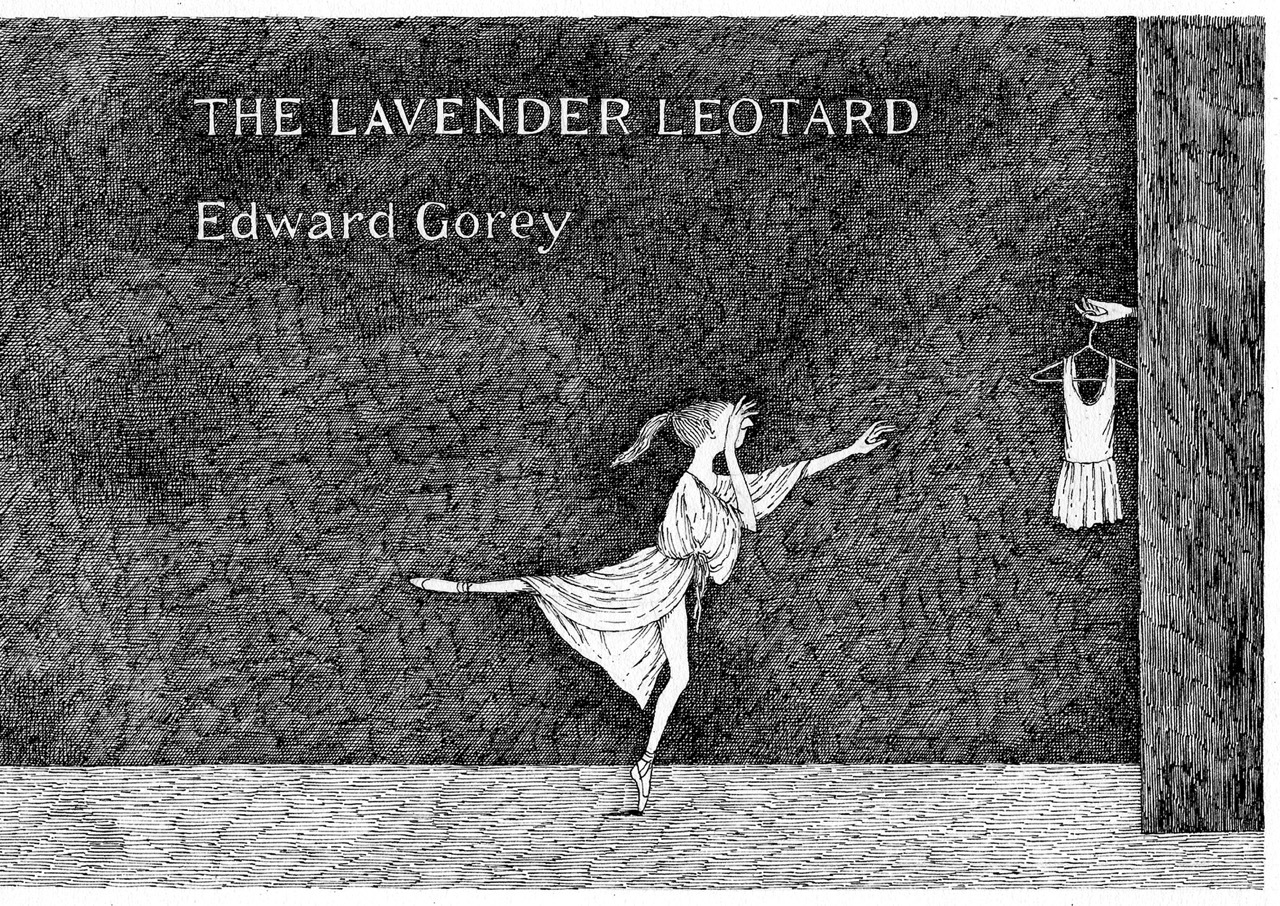

Edward Gorey, The Lavendar Leotard, Gotham Book Mart, 1973.

On the other hand, unknowability is one of the great qualities of Gorey’s work. His desires may be indecipherable, but they crept into his books nonetheless, taking the form of an abiding sense of loneliness and the comic absurdity of life that is both unsettling and consoling. His drawings feel subversive, as if he’s turning over pleasant notions of prosperity and nostalgia to find the worms underneath. They’re full of his difference, and they welcome you to your own. It seems safe to say that those alphabetical kids don’t stand for Gorey’s own unhappy childhood. What’s being murdered is the normalcy of it all.

Julie Phillips is the award-winning author of James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon. She lives in Amsterdam and is working on a biographical book about creativity and mothering, for which she received a Whiting nonfiction grant. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, Ms., and the Village Voice, among others. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.