Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Bury Mama in the yard: a new show explores the art of feminine

self-eradication.

Aneta Grzeszykowska, Mama, 2018. 50 photographs in paper album, cloth binding, 17.52 × 13.58 × 3.74 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

Aneta Grzeszykowska, Lyles & King, 106 Forsyth Street, New York City, through November 18, 2018

• • •

“Ja, to ktoś inny.” Je est un autre, I is someone else. Curator Hanna Wróblewska invoked Rimbaud’s twitching line of self-dispossession to open her essay on Katarzyna Kozyra’s Men’s Bathhouse (1999), a video in which the artist wore a cast of a friend’s penis to infiltrate a “safe” male space. An icon of Poland’s “critical art” scene from the early ’90s through the millennium, Kozyra and her fellow provocateurs were scandalizing the public in the heady early days of a new democracy. And as it had in the past, her work triggered a media firestorm; Kozyra ultimately decamped for Berlin.

Aneta Grzeszykowska had just finished art school when the anti-Bathhouse campaign erupted, and had her first solo show soon after another artist, Dorota Nieznalska, was charged with blasphemy for exhibiting a penis on a cross. Like other Poles working in the wake of such attacks on “indecent” women artists (attacks that were sometimes physical), Grzeszykowska has been comparatively temperate in her practice. Instead of threatening male institutions or bodies, she assiduously effaces her own. There’s that same forensic desire to saw apart and rearrange identities, but turned inward. “I is someone else.” Ja, to ktoś inny.

Aneta Grzeszykowska, Mama, installation view. Photo: Charles Benton. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

Grzeszykowska’s trademark enthusiasm for self-eradication (what she has called a “theory of nonexistence”) reaches uncanny heights in her new solo exhibition at Lyles & King, where she replaces her body altogether. In 2017, she had two friends who work in the movie business cast a lifelike silicone model of her head and nude torso, complete with real hair follicles. The eerie process was documented in an untitled group of eight color photos, which ends with Grzeszykowska’s impassive rubbery face wrapped in plastic, looking like an oddly complacent victim. At Lyles & King, we see the doppelganger resurrected in Mama (2018), a series of fifty numbered photographs, sixteen of which are on view in the main gallery. (A complete book version is also available, which helps reveal the project’s sense of cinematic narrative.)

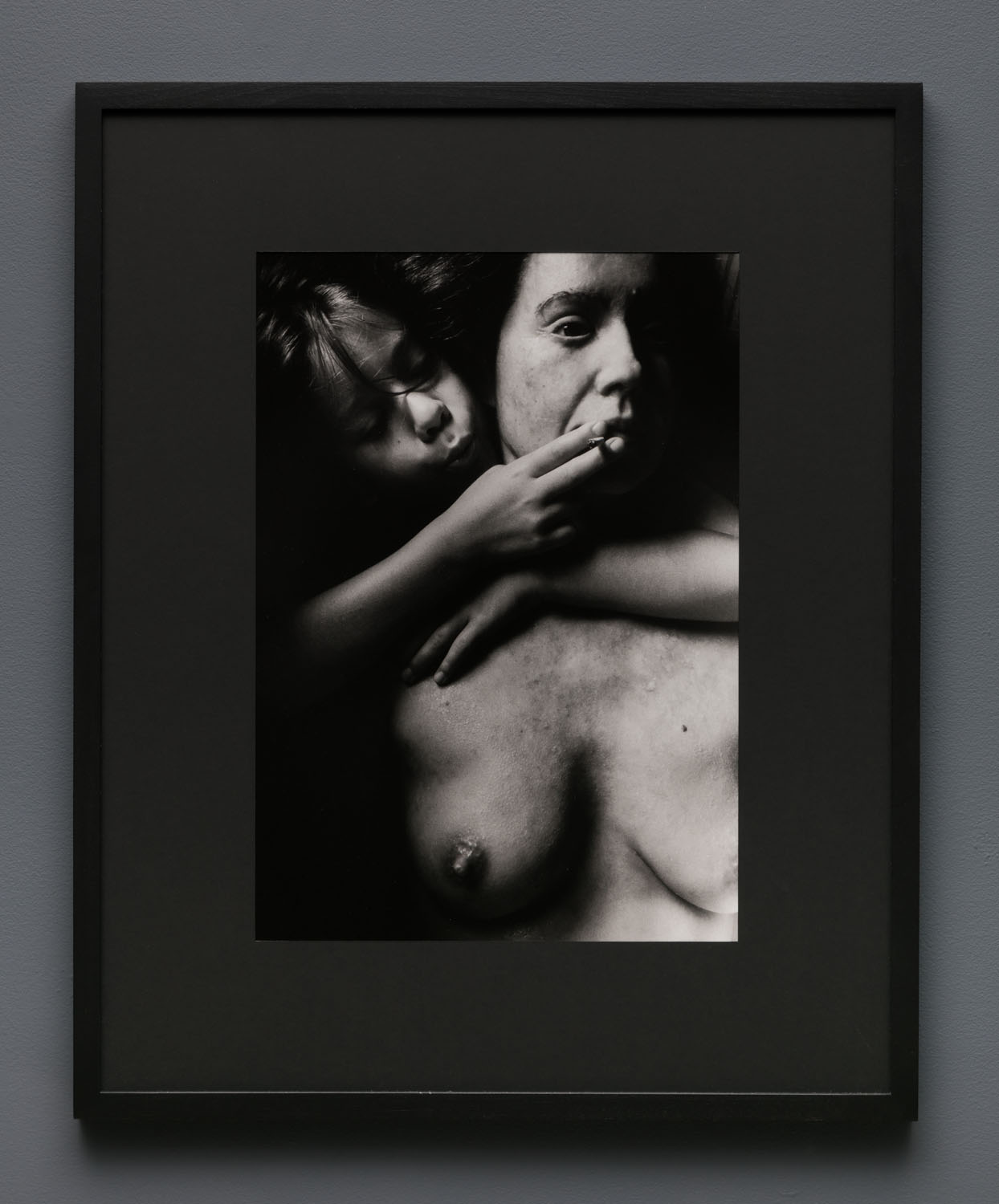

Aneta Grzeszykowska, Mama #34, 2018. Gelatin silver print, hand-printed by the artist, 19.625 × 14.145 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

The photos are shot beautifully, some in a gentle, nostalgic black-and-white, some in warm, saturated colors. They often evoke recognizable art-historical imagery—recalling devotional scenes with their soft and tender lighting; nodding to Francesca Woodman’s dreamy, apparitional self-portraits; quoting David Wojnarowicz’s startling photo of a partially buried face. Given this beauty, their calmly deployed brutality is all the more jarring. The images star Grzeszykowska’s eight-year-old daughter, Franciszka, a perennial element in her mother’s work (in a troubling photo from the artist’s 2014 Selfie series, for instance, the child’s plump little hand grips dead pigskin models of the artist’s fingers). Mama’s sequence begins with Franciszka pulling the silicone bust out of what looks like a body bag and rinsing it off in a utility sink. She puckers her mouth behind the dummy’s shoulder, enticing it to accept the lit cigarette she offers between her girlish fingers. She totes the halved body to the lake in her wagon; then Franciszka is laying underwater, gulping for air, right next to her mother’s submerged, unblinking double. The narrative concludes with the girl interring “Mama” in the yard, Grzeszykowska’s waxen features meekly emerging from the dirt.

Aneta Grzeszykowska, Mama #50, 2018. Pigment ink on cotton paper, 19.625 × 14.145 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

Grzeszykowska considers herself a performance artist, one living for the camera. Taking pictures can be part of the action, or a means to create an exactly controlled document of it; but she especially believes that it makes the performance more real (the inert dummy looks far more human in photographs—in “real” life, it’s just a fake). Beauty Masks (2017), also on view at Lyles & King, presents five more portraits of the artist—in the flesh this time, but going through a related process of photographic transformation. She’s pictured severely erect, her face consumed by the beauty masks in question (which are sold to improve skin quality or help women recover after plastic surgery, but which look more like torture devices). Instead of a realistic doll, now Grzeszykowska becomes a hybrid sculpture, a formal assemblage of grossly chapped and swollen lips, painfully stretched nose, and vacated eyes gazing to the side, all held together by the masks’ Pepto-pink plastic, hospital-beige fabric, or industrial-orange rubber. The portraits are shot in the cool, clinical style of a sci-fi ID photo, or a piece of scientific evidence.

Aneta Grzeszykowska, Beauty Masks, installation view. Photo: Charles Benton. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

The images at Lyles & King are weirdly attractive, stirring up a sharp, pleasurable anxiety (I kept returning to a particularly grotesque one of a delighted Franciszka taping a set of dentures onto her fake mother’s mouth, creating a grinning death mask; flipping back to it in the photobook was like poking at a tooth that hurts, enjoying the little shock). But I was also skeptical—the ideas seemed thumpingly obvious. To be woman is to be thing, to give life is to give death, to conform to beauty standards is to self-mutilate; this is well-trod ground.

But that same obviousness could also be part of the work’s ability to disturb. I might be embarrassed by her bluntness, but Grzeszykowska is not: this is just her as other, as fragment, as dead, and that’s it. Mama feels even more shivery when considered in the context of Grzeszykowska’s whole practice, which she has discussed unsentimentally using words like “dismemberment,” “suicide,” and “rape.” In photos and film, she has ruthlessly staged her disappearance, her sublimation into other people, and the chopping up of her body in various ways. She has repeatedly transformed her “I” into an “it,” replicating bits of herself with dead animal flesh or synthetic materials. She has an avowedly noncommittal affiliation to feminism, and is annoyed when critics insist on her gender, but she is clearly handling identity categories (woman, mother, Central-Eastern European) that imply a destabilized subjectivity. Instead of trying to resolve that instability, Grzeszykowska twists the knife.

Aneta Grzeszykowska, Mama #01, 2018. Pigment ink on cotton paper, 19.625 × 14.145 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

It’s important that Grzeszykowska strives to perfectly capture that self-inflicted slicing, making sure we can see her vanishing, in aesthetically pleasing images that make the violence polite. It’s hard not to think about what that means in today’s Poland, where an ultra-right-wing nationalist government has taken power. This government has established a cultural department to police national memory, fired directors of public cultural institutions for showing “too much Jewish content” or not enough “Christian values,” and threatened opposition writers with military trial. It is also trying to completely criminalize abortion (which is already nearly illegal), recently defunded domestic abuse programs because they “discriminate against men,” and has ordered security forces to raid women’s rights NGOs. Current events are emphatically not the stuff of Grzeszykowska’s work; but insisting, again and again, that people watch as you self-cannibalize your pretty female body for your art seems keenly political against that backdrop.

In her 2010 essay, “A Thing Like You and Me,” the German artist and writer Hito Steyrel cryptically wrote that “becoming a subject can be tricky. The subject is always already subjected. How about siding with the object for a change?” I remembered that line looking at Grzeszykowska’s silicone self, thinking about her commitment to becoming a thing, a thing among things. Ja, to coś innego. I is something else.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns.