Nick Pinkerton

Nick Pinkerton

Remembering the film world’s legendary iconoclast.

Jonas Mekas at Anthology Film Archives opening, November 1970. Photo: Gretchen Berg. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

A moving-image medium unfolding in real time, cinema seems intrinsically suited to the business of capturing life—so why should it be that so often movies, even or especially those that are magnificent technological achievements, evoke only a fraction of the emotional and pictorial interest of a stroll around the block? Among the many passions pursued by Jonas Mekas, the filmmaker, poet, cut-rate bon vivant, diarist, columnist, curator, and cheerleader for audience-defiant art who died last Wednesday at age ninety-six, was just this: a cinema as rich and disorienting and sad and ecstatic as lived life itself.

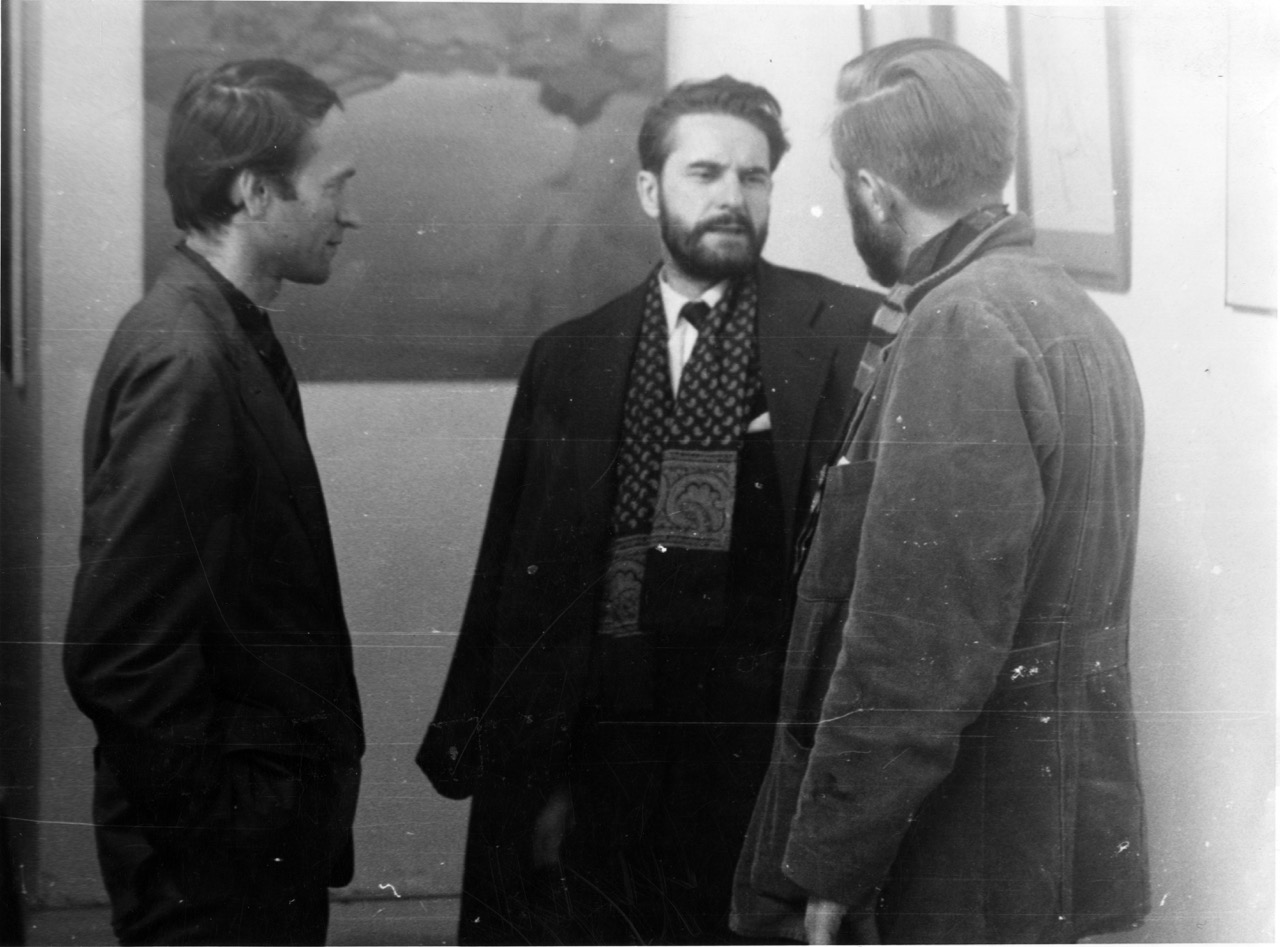

Jonas Mekas, Adolfas Mekas, and Stan Vanderbeek. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

And his was an epic of a life. It may seem as though Mekas, born of peasant stock in rural Semeniškiai, Lithuania, in 1922, was never young. His youth belonged to a world that burned in wartime—a world he left behind in 1949, when, following a stint in a German forced labor camp, he and his younger brother, Adolfas, immigrated to the US. They settled in the Lithuanian enclave of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which he began to record with a borrowed 16mm Bolex. Some of what he shot would eventually appear in his bittersweet epic Lost, Lost, Lost (1976), which recounts the process of turning away from his European past to become an American artist. This was one of a series of diary films he would produce in which juddering offhand imagery and gamboling camerawork are accompanied by the author’s narration, his lilting elocution seeming to embody the driftless state he so often returns to.

Still from Lost, Lost, Lost (1976), by Jonas Mekas. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

He was a contemporary of those other American diarists, the Beats; he was born the same year as Kerouac, whom he outlived by a half century. By the time he became the figurehead and chief proselytizer for what he by the early ’60s was regularly referring to as the New American Cinema, he was an elder statesman, old enough to be the father of the Kuchar Brothers. Never having been young, Mekas was spared being truly old—which isn’t to suggest he was immune to physical attrition but that he refused to shut himself off to the world as he aged: you can find pictures of him in Zuccotti Park in 2011; video of him defending Britney Spears’s right, as an artist, to her nervous breakdown. It may seem ridiculous to speak of the death of a ninety-six-year-old man as shocking, but we must make an exception in the case of Mekas.

First, Mekas wrote. In 1954 he cofounded, with Adolfas, the magazine Film Culture; four years later he began to contribute a regular column, his “Movie Journal,” to the Village Voice. His writing tends toward the exhortative and the lyrical rather than the analytical—he called himself a midwife rather than a critic—and he earned enemies, among them Amos Vogel, whom Mekas would supplant as the brilliant doyen of New York experimental film culture. (If a man lives for nearly a century making only friends, his life may be said to have been squandered.) As a writer, Mekas was renowned as a champion of work that would variously be categorized as avant-garde, underground, and independent, but his tastes were extremely catholic: he rhapsodized about the westerns that played to all-male audiences on Forty-Second Street and the sex movies that played Hoboken, and it was he who gave a platform to Andrew Sarris, whose “Notes on the Auteur Theory” was published in Film Culture in 1962, opening the door to a necessary reappraisal of the art of indigenous Hollywood product.

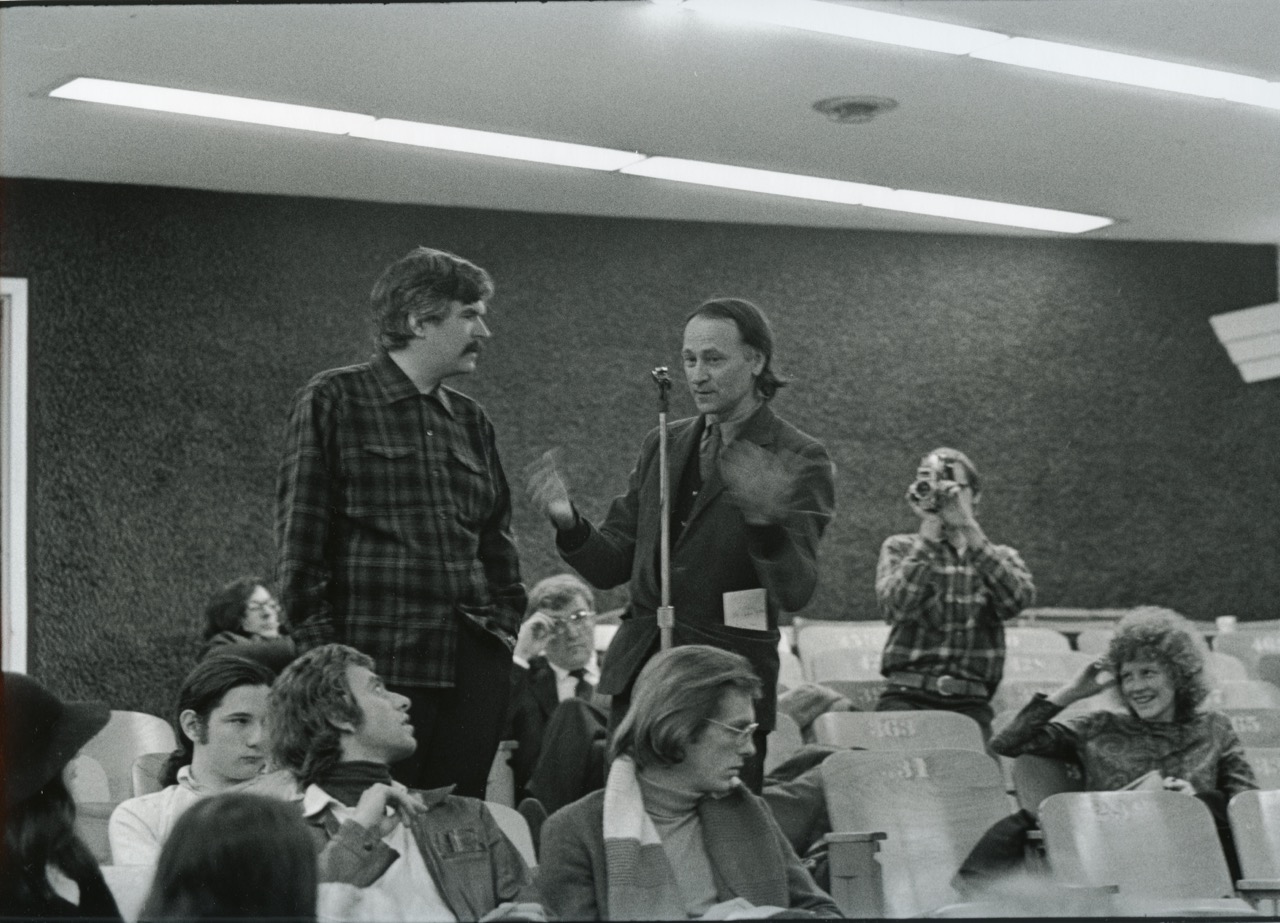

Stan Brakhage and Jonas Mekas at SUNY Buffalo conference, March 1973. Photo: Robert Haller. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Mekas is re-readable, not, like Sarris, for epigrammatic concision, but for his combative recklessness, and above all the pleasure of his company; you can hear his playful, accented voice when you read him. He is exciting and sometimes terrible but never professional, the antithesis of the indifferent, above-the-fray gentleman critic, and his role as pugilistic polemicist led him naturally to that of filmmaker. He struck on the form that he would revisit and refine through his life with Walden (Diaries, Notes, and Sketches) (1969), a three-hour condensation of cinematic impressions collected through the mid-1960s, crisscrossed by appearances from the likes of the Velvet Underground, Stan Brakhage, and Stephen Shore.

Still from Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972), by Jonas Mekas. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

From such rarefied company, Mekas returned to his lost homeland to shoot Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972). This movie diary ends with a visit to the filmmaker Peter Kubelka in his lifelong home of Vienna, where images of a centuries-old monastery library, a vision of solidity and permanence, are contrasted with scenes from 1971 of the city’s old fruit market in flames—for the forces of destruction threaten even the most immovable and immortal-seeming institutions. As an émigré, Mekas was unusually sensitive to the memory of what had been lost in the fire, and taken together his films and writings suggest the work of a hoarder of experience, clinging to precious images. He is, as such, an essential witness to the atmosphere of cross-pollinating creativity in postwar New York, while later works like My Mars Bar Movie (2011) provide insights into the material transformation of a moneyed New York that makes less and less space for the marginal, the unhygienic, and the eccentric—all of the qualities that Mekas prized in life and in art. His memory was prodigious, right up to his last autobiographical feat, the recording of an over six-hour oral history for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum prompted by an article published last summer that raised questions about his wartime associations.

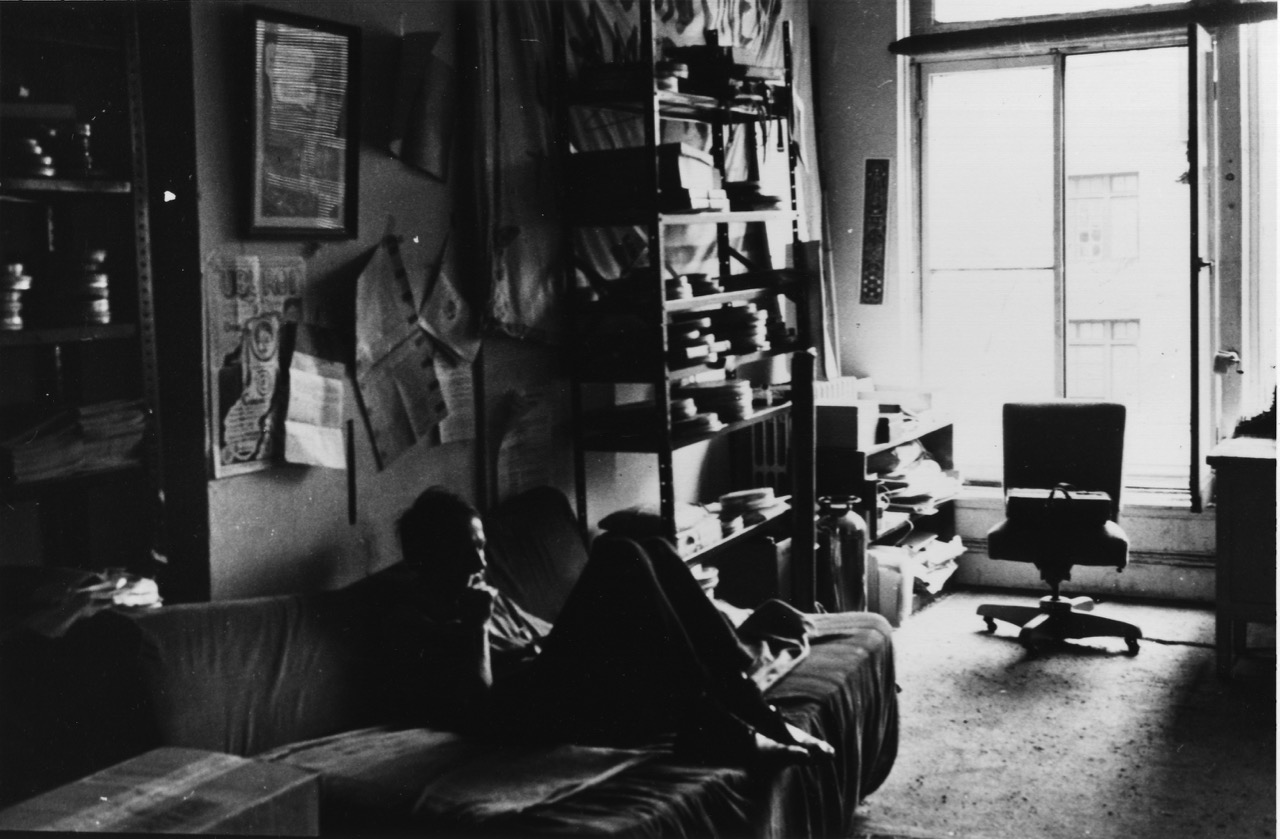

Jonas Mekas in the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, circa 1963. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

The preservationist instinct guided Mekas in his other great calling, that of curator and keeper of a new crazy-quilt canon, the so-called “Essential Cinema” list. In 1962, over the objections of Vogel, he led the creation of the artist-run Film-Makers’ Cooperative distribution group, which continues to operate today. Coop filmmakers would in turn provide the backbone of Mekas’s screening series, the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque—while praising the messy in art, Mekas was a genius of organizational synergy. In 1970, the enterprises of this wanderer found a brick-and-mortar dwelling at Anthology Film Archives, which moved around lower Manhattan before landing in its present and permanent home on Second Avenue and Second Street, and which I made a beeline for on my first visit to New York in 2001.

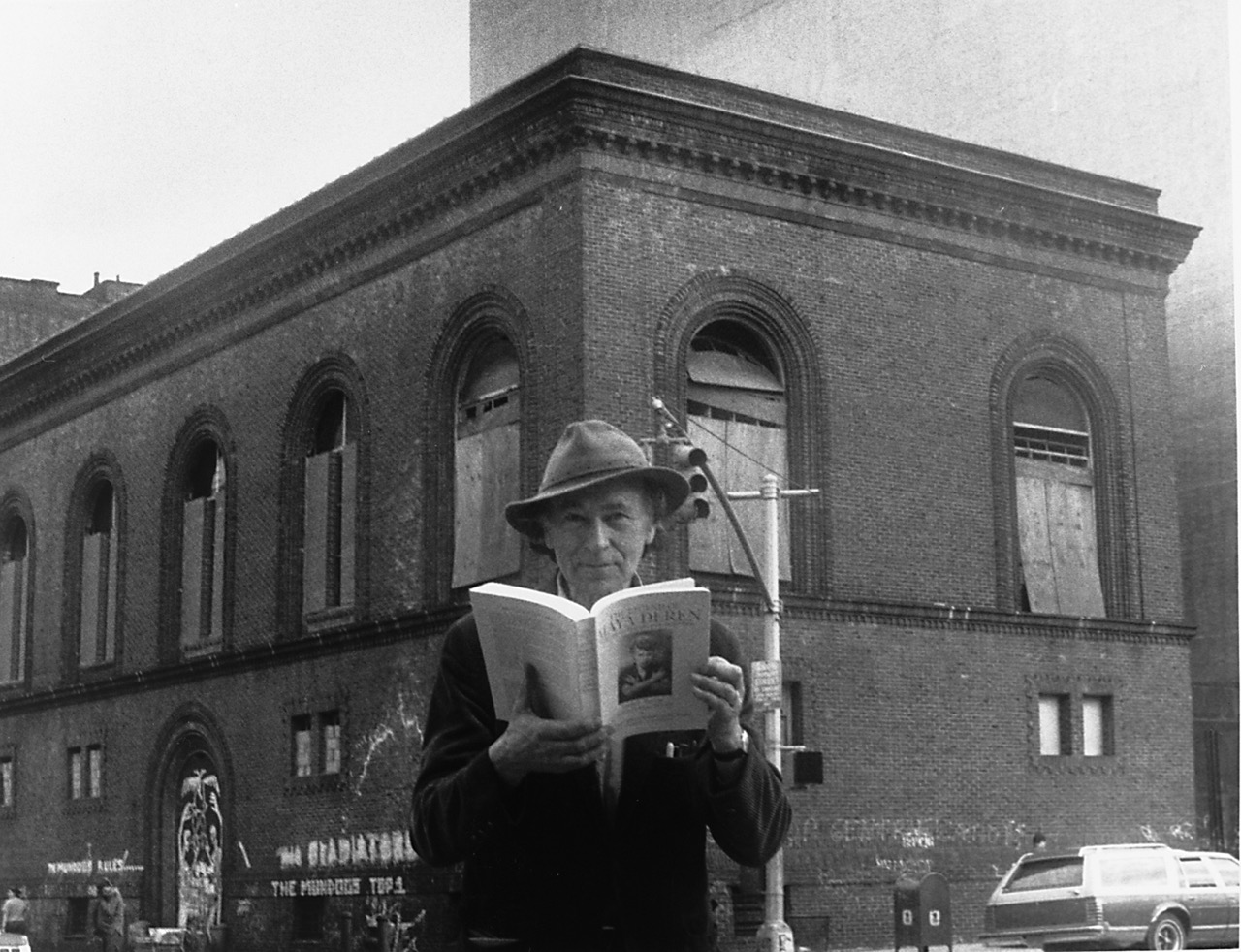

Jonas Mekas outside the future home of Anthology Film Archives, Second Avenue and Second Street. Photo: Hollis Melton. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Then as ever since I was awestruck by the programming mandate at Anthology, set in no small part by Mekas, who gave not a tinker’s damn about getting asses in seats—it was he who selected the titles for a series forbiddingly titled “Boring Masterpieces.” A former court building with barred windows, Anthology is Mekas’s ultimate monument, a fortress of cinema, a bulwark against populist pandering and the ravages of time, and a temple to the free creative act, which he advocated in defiance of the ever-advancing, implacable forces of entropy. “Everything falls to dust anyway,” he told an interviewer, in 2017. “And yet, you keep making things.”

Nick Pinkerton is a Cincinnati-born, Brooklyn-based writer. His writing appears regularly in Artforum, Film Comment, Sight & Sound, frieze, Reverse Shot, and sundry other publications, and in areas of interest, he covers the waterfront.