Ben Ratliff

Ben Ratliff

Emperor Tomato Vinyl: dropping a needle on the band’s

remastered albums.

Stereolab. Image courtesy stereolab.co.uk.

Transient Random Noise-Bursts With Announcements, Mars Audiac Quintet, Emperor Tomato Ketchup, Dots and Loops, Cobra and Phases Group Play Voltage in the Milky Night, Sound-Dust, and Margerine Eclipse, by Stereolab, Duophonic (Reissue)

• • •

In 2003, a new thread started up on I Love Music, the online message board frequented by music writers and obsessives, many of them British. It was called “The Future of Stereolab,” because it addressed a simple question: Does the band Stereolab have one? The reason for the question was that Mary Hansen, singer and keyboardist, had died at the end of 2002; and because Lætitia Sadier and Tim Gane, the married couple who worked as the band’s principal lyricist and songwriter, respectively, had separated. It was unclear whether the band would carry on.

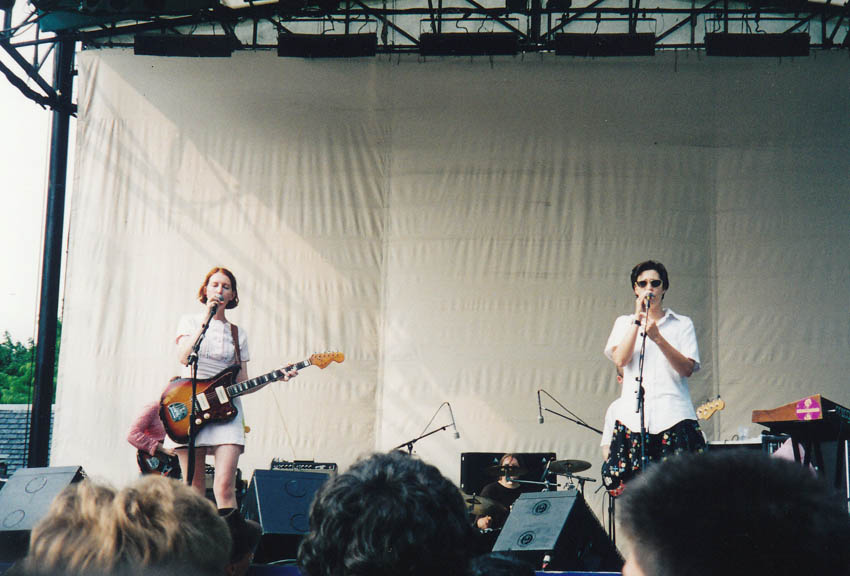

Mary Hansen and Lætitia Sadier perform with Stereolab in Central Park, New York City, July 22, 1995.

In fact it did carry on, until 2009. But that phrase, “The Future of Stereolab”—the thread is still live on the I Love Music website—unwittingly said it all. It was a critical Bingo shout. It got the band’s tastes, organizing principle, achievement, paradox, and dilemma all on a plate.

Over the course of 2019, Stereolab has released five of its albums in remastered form, with much annotation, metadata, and ephemera: Transient Random Noise-Bursts With Announcements (1993), Mars Audiac Quintet (1994), Emperor Tomato Ketchup (1996), Dots and Loops (1997), Cobra and Phases Group Play Voltage in the Milky Night (1999). Two more—Sound-Dust (2001) and Margerine Eclipse (2004)—will be available on November 29. To listen to them properly entails thinking about the past, the future, the “past,” the “future,” and the present.

Stereolab, founded in London in 1990, made music that often cleverly or obscurely suggested the “future,” influenced by past avant-garde or populuxe projections of it in music, film, and politics. The band’s reference points included the Beach Boys and expanded cinema; Sun Ra’s open-system vamping and Steve Reich’s through-composed minimalism; John Barry’s film scores and early computer music; early-’70s krautrock and the drones and stomps of Velvet Underground’s 1969 live record; and in its lyrics, axiomatic thoughts on commodification, power relationships, and cycles of history adapted from revolutionary thinkers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—which ones, it was never completely clear. It didn’t matter: the dialectic lived right in Stereolab’s sound. Many of its songs were built on twin counterpoint lines, a thesis and an antithesis, starting with Sadier and Hansen’s vocals and helixing down through the rest of the music’s repetitions and modular loops.

Stereolab, the Lizard / Sausage Machine Christmas Party, Camden Irish Centre, London, 1994. Photo: Greg Neate.

Stereolab summoned ghosts of the past a lot, until it got to a point—I’ll call it the late ’90s—when the group fully embodied its own present. For these few years it connected materially with the Chicago scene around Tortoise and the Sea and Cake, and spiritually with hip-hop. (In 1997, Stereolab’s Dots and Loops and Wu-Tang Clan’s Wu-Tang Forever were both new. I remember hearing the fourth movement of Stereolab’s “Refractions in the Plastic Pulse” right after Wu-Tang Clan’s “Reunited,” and thinking: similar tempo, similar funk drumbeat, an analogous staccato violin riff; each came to this through separate means. Has it happened? Have the universes converged?) But after 2003—also the beginning of Myspace, the iTunes library, and the Iraq war—the band itself became a ghost: it lacked a real future even as it evoked an ersatz one. Its final records sounded a bit wan, twinkly, over-precise.

The band’s long late phase overshadowed its early achievement. As usual, listening is the only corrective. The only way to know what Stereolab was really about is to hear their old records. And even though Stereolab’s time span was the CD era, I do mean records. The LP reissues are meticulous, including demos, outtakes, alternate and instrumental mixes, and liner notes by Gane disclosing the origin stories for each track. The reissued albums are all on streaming services, but their LP versions—especially starting with Emperor Tomato Ketchup—put their sound, particularly their complicated midrange, in proper dimensions. This is music about other people’s records, OK; it is also about jostling tones and timbres of unusual analog electronics, instruments slightly out of rhythmic sync with one another, irresolute combinations of real-time band and studio band, time expanded and foreshortened.

It is also music about doubt and hope. An unmistakable and willful anxiety, skepticism, and hardened thoughts about a future—if not “the future”—reside there. They can be found in Sadier’s lyrics; one of Stereolab’s most repetitive and noisiest songs, “Crest,” from Transient Random, has three lines, sung in contrary motion to the guitar riff:

If there’s been a way to build it,

There’ll be a way to destroy it,

Things are not all that out of control.

And they can be found in Gane’s compositions, which suggest an ongoing relationship between hard noise and soft kitsch.

Music measures time; it is made in time; it sends messages from its time. Put on the new LP version of Cobra and Phases Group, a record given punitive reviews in Pitchfork and NME when it came out. Sit in a room in your calendar year of 2019, and do the work of listening: let side A play continuously to the end. I have heard the album on Spotify, through Bluetooth earphones, and been half-interested. I have heard it on the new vinyl, through ordinary speakers, and been riveted. You hear more of the information, rife with paradoxes: in sync / out of sync; jamming/postediting; serious/silly. (The brass arrangement tag on “The Free Design” is heisted from Abba’s “Dancing Queen.”) Then turn it over and listen to side B. (Sides C through F still await you, including a new edit of “Blue Milk,” expanded from eleven and a half minutes to seventeen.) This may be the only way to hear Stereolab’s imagined past and future, but also what was its present, and what is yours.

Stereolab performing at Primavera Sound, Parc del Fòrum, Barcelona, June 1, 2019. Photo: Raph_PH.

This year Stereolab reformed to play more than forty shows around the world. The band does not quite exist, and—not “but”—it’s back. The degree to which it exists or is back depends on how much either it, or you, believes in a present and a future. Much of the Stereolab gig I saw in September in Brooklyn seemed almost perfunctory: more product than process, a pretext for selling thirty-dollar T-shirts. But near to the close of the set, a member of the night’s opening band, Bitchin Bajas—Rob Frye—joined them on flute, stretching out a song, making it unclear how and when it should end. Suddenly Stereolab had a present and a future—the future of the next phrase, the future of the next four bars, the future of the next five minutes. That’s all it took. It wasn’t much.

Ben Ratliff is the author of four books, including Every Song Ever.