Simon Reynolds

Simon Reynolds

Robots meet theremins meet Wordsworth: on her album Ealing Feeder, a musician explores electrical mysticism.

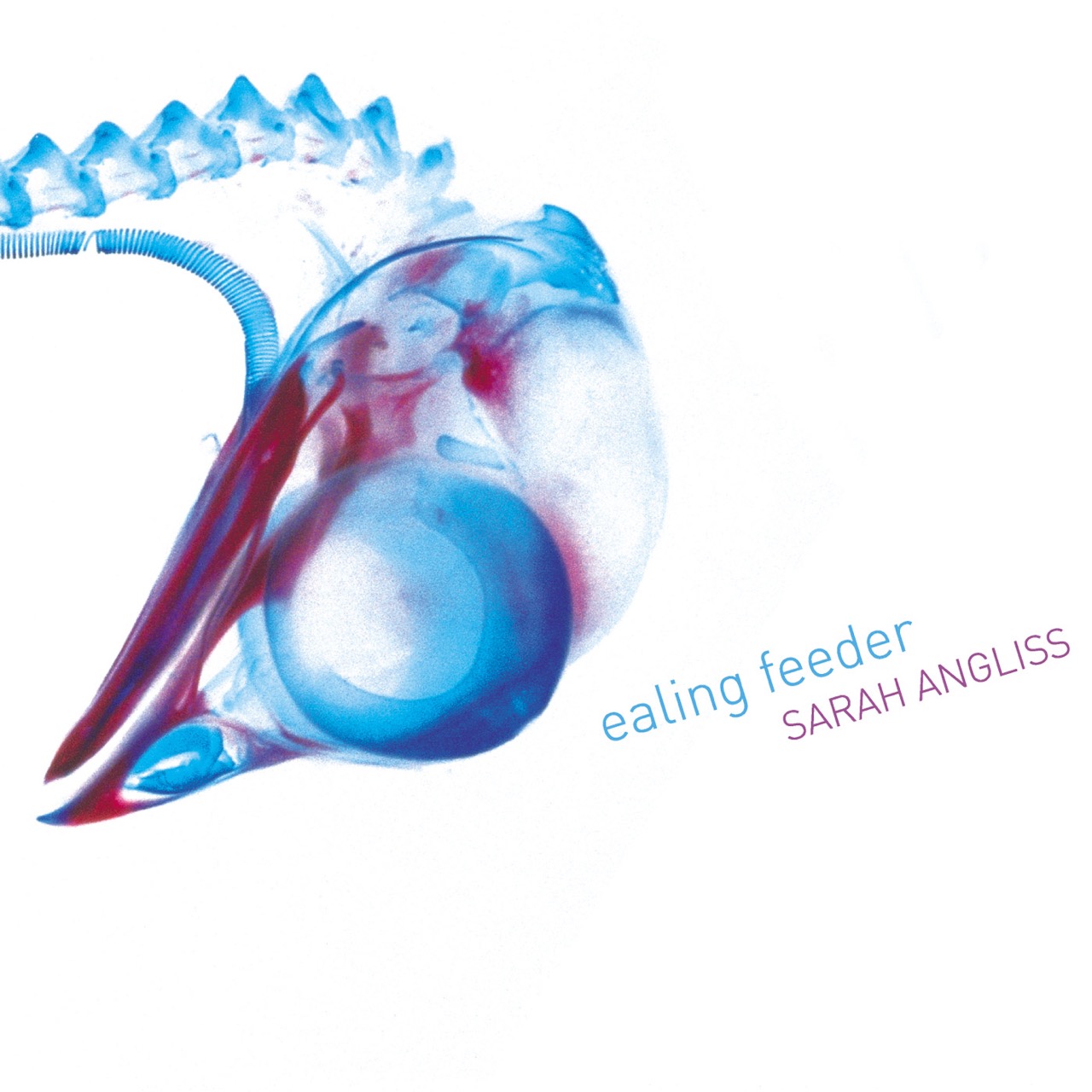

Sarah Angliss, Ealing Feeder

• • •

Ealing Feeder, the debut from British musician Sarah Angliss, is the most inventive album I’ve heard in a long while. Partly that’s down to its hard-to-classify interlacing of electronic and acoustic textures, ambient atmosphere and song form. But it’s also “inventive” in the literal sense: a substantial swathe of the sounds you hear originate from instruments Angliss either built herself or radically adapted.

The album’s title comes from the name Angliss gave one such creation. The Ealing Feeder is a robotic carillon whose twenty-eight handbells can be set to strike in patterns faster than a human player could manage, stirring up a miasma of delicately clangorous chimes. Another prominent color in Angliss’s palette comes from the theremin. Although Angliss deploys the “classic” theremin sound—keening and ethereal—she’s also devised a way of getting the machine to modulate bird-song samples. That trick pops up several times on Ealing Feeder, most notably on “A Wren in the Cathedral,” where the name of seventeenth-century architect Sir Christopher Wren is amusingly literalized as the liquid chirrup of that same bird, famous for its complex and piercing song.

Still from “A Wren in the Cathedral” music video, directed by Tom Hadrill. Image courtesy Sarah Angliss.

Behind Angliss’s ingenuity stretches a long, discontinuous tradition: composers whose longing for unfamiliar timbres took them beyond ruses like prepared instruments or unorthodox playing techniques and into the construction of completely new instruments. Think Harry Partch, America’s “hobo composer,” who from the late 1930s onward built his own assemblages like the Cloud Chamber Bowls and the Mazda Marimba (made out of lightbulbs!). Starting in the early 1950s, the French brothers François and Bernard Baschet devised glass sound structures like the Cristal Baschet. Earlier figures from the same experimental UK scene as Angliss, who is fifty, also resorted to creating new instruments. Originally a sculptor, Max Eastley makes sound-generating contraptions like the water-based Hydrophone, while the Bow Gamelan Ensemble’s site-specific performances were something like an audio equivalent to land art and involved pyrotechnics and noise-making automatons.

“Automatist” is one of Angliss’s own self-descriptions. Her interest in making music machines was sparked by frustration. Starting out as a purely electronic composer, she initially found computers hugely empowering, but as both a performer and a spectator she grew dissatisfied with laptop gigs (all too often, a static figure hunched over a screen). Building contraptions to keep her company onstage was a way of exploiting the theatrical possibilities of performance. The way that her inventions—whose inner workings she often leaves exposed to the audience’s gaze—seem to hover in a zone between alive and not-alive also appeals to her artistic attraction to the uncanny.

The Ealing Feeder. Image courtesy Sarah Angliss.

Listening to Ealing Feeder at home, of course, you don’t see the Ealing Feeder or its sister machines in operation. It’s a testament to Angliss’s imagination and sheer musicality that the album works just fine as a stand-alone audio experience. The sound draws across the spectrum from digital (the programming language MaxMSP) through electro-mechanical (the self-cobbled machines) to acoustic (Angliss’s primary instrument is the recorder, and she also plays that musical-hall novelty, the saw). Technology is always present but never in an overbearing way. Opening track “You Taught Me How to See the Crows” starts with the forlorn cawing of a recorder, which is joined by another melodic curlicue on the same instrument, and then another. . . . It’s only toward the end of the piece that the listener cottons on that a loop pedal delay system is involved, multiplying and interweaving the signals, creating an effect that is rather like crows landing one by one in a bare wintry field.

Actual field recordings are also part of Angliss’s arsenal: the sirens of emergency vehicles, what sounds like a wrestling match’s rowdy crowd and beefy bodies slamming against canvas, dankly echoing drips documented at a submarine emergency escape training tank. There are also spoken-word recitations and sung vocals from guest collaborators. Both the exterior sounds she’s scavenged and the human presences she’s invited enlarge and enliven the proceedings, simultaneously opening the music to let the world in and giving it intimate foreground focus. That helps forestall the pieces from becoming dark dronescapes of the long-established type pioneered by such ambient industrial outfits as :zoviet*france: and Nurse With Wound. At its best Ealing Feeder sounds like nothing else around and little else before.

Alongside “automatist,” Angliss has also dubbed herself a sound historian. Her research has led her to all kinds of archival curiosities, such as a nineteenth-century clog dance in which factory women from Lancashire imitated the mechanistic rhythms of their cotton mill. Much of Ealing Feeder is informed by esoteric reading. Framed sonically with shudders of overblown recorder and the clatter of tossed coins captured with a jarring hyperreal clarity, “Cow Heart Pin” was inspired by a macabre ritual described in Edward Lovett’s 1925 book Magic in Modern London, in which an East End butcher laid a curse on a rival by perforating a desiccated cow’s heart with nails and pins.

Still from “Cow Heart Pin” music video. Image courtesy Sarah Angliss.

There’s something slightly eerie about the name Angliss itself, as if its phonetic proximity to “English” led her to the subjects that fascinate her. If there’s a loose theme to Ealing Feeder, it’s the sedimentation of history that undergirds modern London: stubborn medieval traces jostling with the manic energy of finance capitalism and the development projects that are ripping up the city. On “Sky Bullion,” improv drummer Stephen Hiscock aggressively duets with the noises of a construction site. On “Ventriloquist,” Colin Uttley recites words that resemble the “roll up, roll up” text on a carnival poster, promising the punters “the marvellous craft / Of modern Merlins . . . / All freaks of nature . . . / A Parliament of Monsters.” Actually they are Wordsworth evoking Bartholomew Fair, for centuries London’s leading street festival, until suppressed in the mid-nineteenth century for its alleged incitement to vice and unruly behavior.

Angliss’s means of production (the robots, the theremin) and arcane interests converge in a kind of electrical mysticism. The name Ealing Feeder originally came from a lever Angliss spotted in the control room of Battersea Power Station, which once controlled the supply to a West London borough. The undercurrents coursing through the entire album become explicit in the wondrous closer “The Messenger,” a Promethean parable that draws partial inspiration from a rhapsodic prophecy of wireless telephony from a century ago that she encountered in Haunted Media (Jeffrey Sconce’s book about the paranormal associations projected onto each new stage of electronic media by the populace).

“The Messenger” starts with a bow-tied male voice from an ancient advertisement extolling the “difference electricity can make in your life.” Female voices—Flora Dempsey and Angliss’s sister Jenny—speak and sing lines about the miraculous power of electronics and telecommunication: “we’re toying with the intangible, the stuff from which the Northern Lights are made,” “call in your loud electromagnetic voice / a small reply will come.” “The Messenger” shivers and crackles with the superstitious awe that greeted the original discovery of electricity, when it was often identified with the élan vital itself. That notion lingers on in concepts like “animal magnetism” or “galvanizing,” words shadowed with older connotations of magic in both the paranormal and carny-show illusion senses. Where science meets the supernatural, where technology becomes tricknology—this is the hinterland that Angliss makes her home.

Simon Reynolds is the author of eight books about pop culture, including Retromania, the postpunk chronicle Rip It Up and Start Again, the techno history Energy Flash, and most recently Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy, from the Seventies to the 21st Century. Born in London, currently resident in Los Angeles, he is a contributor to publications including The Guardian, Pitchfork, and The Wire, and operates a number of blogs centered around the hub Blissblog.