Andrea K. Scott

Andrea K. Scott

The Met Breuer looks back at the colorful work of the late postmodern designer.

Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical, installation view. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical, Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue, New York City, through October 8, 2017

• • •

Serious fun. That’s what the disruptive design genius Ettore Sottsass was up to with his furniture, ceramics, buildings, glassware, textiles, jewelry, and photographs—in other words, with his life, which ended on New Year’s Eve in 2007, at the age of ninety. For all the sensuous whimsy and nose-thumbing irreverence of his best-known work—the lipstick-red plastic Valentine typewriter for Olivetti, from 1968; the more-is-more pile on of color and form of the “Carlton” Room Divider, from 1981—Sottsass was at heart a philosopher, with a deep faith in the power of objects. As he told Charlie Rose in 2004, “If you have good design, you will have a better society.” Of the love-it-or-hate-it Memphis Group, the short-lived postmodern design movement, which Sottsass co-founded with much younger colleagues in his living room in 1980 (and of which “Carlton” is the abiding icon), he told Rose, “We were hoping to make the world a little bit different, less bloody. We were dreamers.” He once described that portable typewriter—which he cursed for its popularity, concerned that he might be written off as a one-hit wonder—as “the sort of thing to keep lonely poets company on Sundays in the country.”

Ettore Sottsass, Valentine Portable Typewriter, 1968. ABS plastic and other materials, 4 ⅝ × 13 ½ × 13 ⅞ inches. Image courtesy Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti. © Studio Ettore Sottsass Srl.

Sottsass himself has more than enough company at the Met Breuer, where the museum’s associate curator of modern design and decorative arts, Christian Larsen, has organized an exciting, if cluttered survey titled Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical. “Radicals” is more like it—nearly half of the show isn’t by Sottsass at all. The result is a show that risks defining its subject more by his influences and his subsequent impact than by his own merits. But considered generously, the strategy jibes with the vision of a collegial polymath who was always as happy to celebrate his inspirations—from pop art to frequent pilgrimages to India—as he was to play éminence grise. (Asked once why he was the best-known member of Memphis, he quipped, “Because I was older.”)

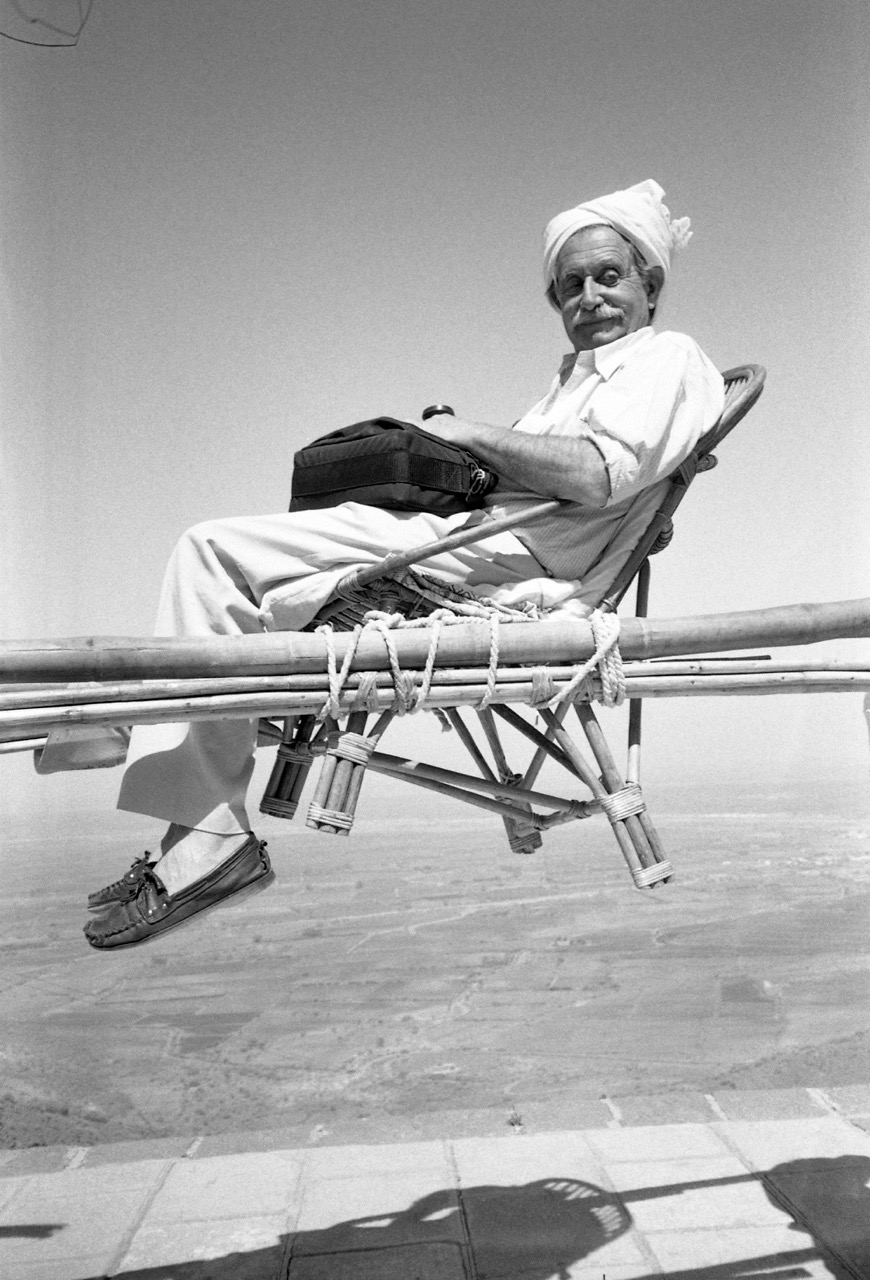

Barbara Radice, Sottsass in India, 1988. Image courtesy Barbara Radice.

From a practical standpoint, however, Larsen’s contextualizing approach may have derived from a time crunch: the show was assembled in only nine months (retrospectives typically take years to plan), relying largely on the Metropolitan Museum’s deep Sottsass holdings, much of it amassed in the 1980s by the museum’s then-curator R. Craig Miller, who later told The New York Times that Sottsass was “one of the towering designers of the late 20th century—I put him up there with the gods.” Fitting, then, that the oldest object on view is a blue faience ankh in the Met’s collection, from 1400–1390 BC, the symbol of life in the Egyptian pantheon; the newest are a trio of low, puzzle-like marble stools, made this year by the Britain-based design duo Oeuffice, on loan from a gallery in Beirut. In between are selections, most of them borrowed in-house, that reveal a head-spinning array of associations and enthusiasms, from works of art (including Kandinsky, Frank Stella, and, in a head-scratcher, Thomas Struth), to artifacts (Hopi katsina dolls, ancient Roman jars, a fourteenth-century Tibetan tapestry), to furniture (from Josef Hoffmann to Frank Lloyd Wright to Piero Fornasetti), and much, much more. In the impudent spirit of Sottsass himself, the result amounts to an anti-survey survey—also a monographic show without a monograph, although Phaidon has just issued a new edition of its beautifully designed doorstop of a book about Sottsass, first published in 2014.

Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical, installation view. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

Sottsass was born into the company of other designers—his father, also Ettore Sottsass, was an architect, in whose footsteps he followed, earning an architecture degree in Turin in 1939. (While alive, Sottsass insisted on appending an American-style “Jr.” to his name in homage to his father, although he had abandoned architecture for industrial design by the time he came to New York in 1956 for a stint with George Nelson, an American kingpin of modern design.) Father and son collaborated on a public housing project in Milan in 1947, funded by the Marshall Plan. The elder Sottsass trained in Viennese modernism, and one of the exhibition’s cleverest conceits is to introduce his son in the context of the stripped-down aesthetics of Wiener Werkstätte and the Bauhaus, upending the received idea of Sottsass as an envelope-pushing ambassador of the garish. If anything, a square wooden planter of Sottsass’s design in the first room of the show, manufactured by Poltronova in 1961, is decorum incarnate when compared to its neighbor, a multi-level metal checkerboard plantstand with a chartreuse interior from 1903 by Otto Prutscher. But Sottsass doesn’t always win in Larsen’s game of compare and contrast. In one gallery, two of Sottsass’s Superbox cabinets—rectangular totems of striped plastic laminate on plywood, dating from 1966 and ca. 1970—wither in the company of an authoritative Donald Judd stack from 1968, an elegant Koloman Moser Cabinet, ca. 1903, and, especially, a mysterious little funerary box entombed in ancient Egypt, ca. 1279–1213 BC.

Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical, installation view. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

Sottsass, ever irrepressible, bounces back around the corner in a room dominated by a gorgeous display of five glazed ceramic sculptures, totemic wonders of concentric design, produced by the Italian ceramic manufacturer Bitossi in 1964–67. (These evolved from smaller works he made while recuperating from a near-death experience, a bout of nephritis in India so severe that he was flown to a hospital in Los Angeles for treatment.) The columns belong to a group of twenty-one works, a rarely seen series titled Menhir, Ziggurat, Stupas, Hydrants, and Gas Pumps (1965–66), which was originally shown at the Sperone gallery in Milan in 1967. The allusion to hydrants and gas pumps presages the postmodernist’s fascination with strip-mall vernacular, a year before Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown set out on their first road trip, in what would become their groundbreaking book Learning from Las Vegas, published in 1972.

The alpha and omega of postmodern design is, of course, Memphis, famously named for a lyric from the Bob Dylan song “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” which was playing in Sottsass’s home the night that the movement was formed. Memphis was also, of course, the name of an ancient Egyptian city, home to the Pyramids. The dueling references of the Memphis Group’s name captures its high-low aesthetic, in which luridly colored furniture made of plastic-clad plywood could bear five-figure price tags. The designs became an instant hit when the collection debuted in 1981 in Milan, only to be laughed off a few years later as a symbol of 1980s excess. When the Memphis Group unveiled its designs in its New York debut in 1982, more than three thousand people lined up in the rain one October night to view them. Karl Lagerfeld decorated his Monaco penthouse in floor-to-ceiling Memphis in 1983, the year he took his job at Chanel, but sold all the furnishings off eight years later, at Sotheby’s. (The auction catalog is now a collector’s item.)

Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical, installation view. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

The movement provides the show’s dazzling finale, a phalanx of bookcases, tables, lighting, and cabinets, installed on a long plinth in the center of the gallery, as if strutting their stuff on a runway, with Sottsass’s “Carlton” room divider as the wildest supermodel. Ringing three walls of the same room, Sottsass’s later work is seen in the company of furniture designed by a mismatched quartet of modern masters: Piet Mondrian, Jean Michel Frank, Gio Ponti, and Shiro Kuramata. The last piece in the show is a Sottsass bed designed in 1992, with a sumptuous pearwood curlicue of a footboard. Its narrow pearly laminate headboard suggests a tall castle wall, with one stone removed, as if to let in the starry night sky. It’s a moving, surprisingly quiet coda to a vibrant career—Sottsass, the dreamer.

Andrea K. Scott is a writer and editor on the staff of The New Yorker magazine, where she has written on subjects ranging from a profile of the sculptor Sarah Sze to an appreciation of the downtown art maven Lia Gangitano.