J. Howard Rosier

J. Howard Rosier

The reconfigurator: in the fashion designer’s exhibition, art history meets sports, rap, and the street.

Virgil Abloh, still from A Team with No Sport, 2012.

Virgil Abloh: Figures of Speech, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 220 East Chicago Avenue, Chicago, through September 29, 2019

• • •

Figures of Speech, a survey of works from the much-disputed fashion designer Virgil Abloh, is a landmark exhibition, a rare instance of an institution like the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago devoting its galleries to the work of a living fashion designer—a figure who in this case is also one of the first black creative directors of a European fashion house. Abloh was tapped to helm Louis Vuitton last year at age thirty-seven, after a swift rise to fame as an enfant terrible in the entourage of Kanye West. (The Vuitton achievement was not welcomed in all corners.) Given the stature of that position, and the prestige, you might expect to find an atmosphere of reverence and sanctity inside the museum, as was the case at the Met’s Rei Kawakubo survey in 2017—the last major US exhibition of a living fashion designer—where garments were displayed like statues, their intricate constructions framed by geometric cubicles and antiseptic white walls. In Chicago, however, the clothes are hanging on the wheel-in racks you’d see at Zara or Uniqlo. They are clumped together haphazardly, like in an apartment closet—displayed more for living than for viewing. In Virgil Abloh’s universe, everyone is comfortable.

Virgil Abloh: Figures of Speech, installation view. Photo: Nathan Keay. © MCA Chicago.

Stand close, and you’ll see logos from Ralph Lauren Rugby and Champion: dead and cheap brands, respectively, that Abloh breathed new life into in 2012 by printing “Pyrex 23” on their flannel shirts and gym shorts, combining the glassware brand of choice for cooking crack cocaine with Michael Jordan’s jersey number to remark on black aspiration. Abloh had bought the deadstock merchandise for under $80 a piece. He then sold each item for up to $720 under the name Pyrex Vision, his first fashion line, named for his alter ego in the self-mythologizing DJ boy band Been Trill. The label garnered cosigns from Jay-Z and the A$AP Mob before catching fire on internet marketplaces, consistently selling out until he shut the line down in 2013.

Been Trill group DJing, including Virgil Abloh, Matthew Williams, Florencia Galarza, Heron Preston, Justin Saunders, 2013. Photo: Matthieu Genre.

Part of the appeal lies in the absence of tension between Abloh’s appropriations and a desire to make the work “his.” The sources aren’t changed so much as reconfigured to suit his purposes. He notoriously copied a Paul McCobb Planner Group chair, making it his just by sticking a small red triangle under one leg, for a collaboration with Ikea. One of his signatures is transparency. Another is his reckoning with what he calls the tourist-purist divide: that gulf between the eager, curious outsider and the often disdainful, highly educated connoisseur. His sources are canonical enough for skeptical “purists” to grant them legitimacy, while his transparency welcomes those “tourists” who are as-of-yet unexposed to those references. That hospitality works throughout the exhibition, letting viewers in on Abloh’s methods, his progression as a designer, and the Factory and readymade traditions informing his work.

IKEA × Virgil Abloh. Image courtesy IKEA.

Also hanging on the racks are thrillingly original pieces from Off-White, the Milan-based label Abloh launched in 2013 to move beyond cult-hero status by applying his cross-referencing skills to a more sophisticated production line. Abloh’s floral long dress from spring/summer 2018 is an asymmetrical tangle of folds falling into an elegant A-line, while his denim explorer coat from spring/summer 2019 is a jean jacket masquerading as an anorak adorned with translucent sequins that make it look like it’s been rained on, or imported from Mars. Hung on the walls in the same room are screen-print stencils of Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ (used to embellish the fronts of Pyrex Vision tees and hoodies), the United Nations logo (Abloh’s signature mark on his DJ flyers, until the UN asked him to desist), and the phrase “Watch Your Back”—all displayed prominently, resembling works of pop art.

Virgil Abloh: Figures of Speech, installation view. Photo: Nathan Keay. © MCA Chicago.

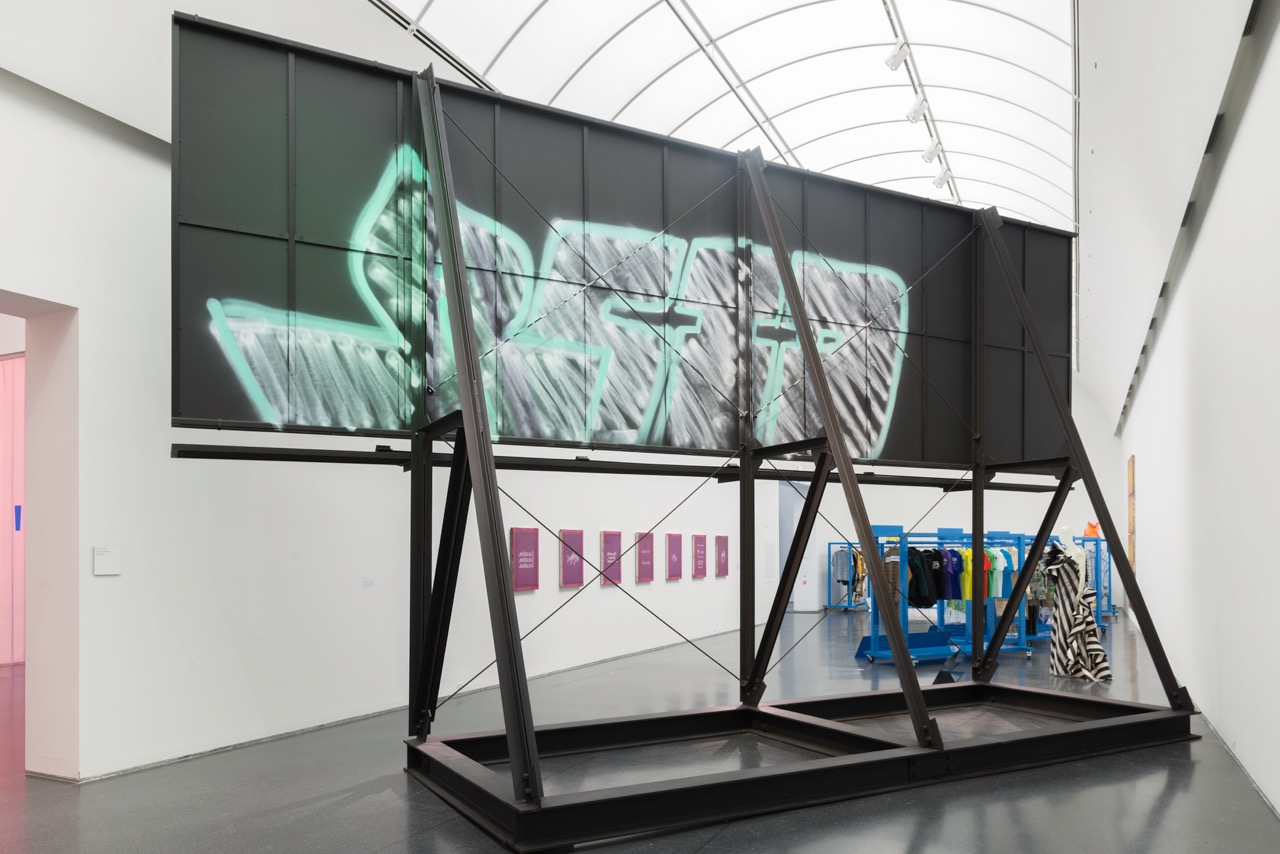

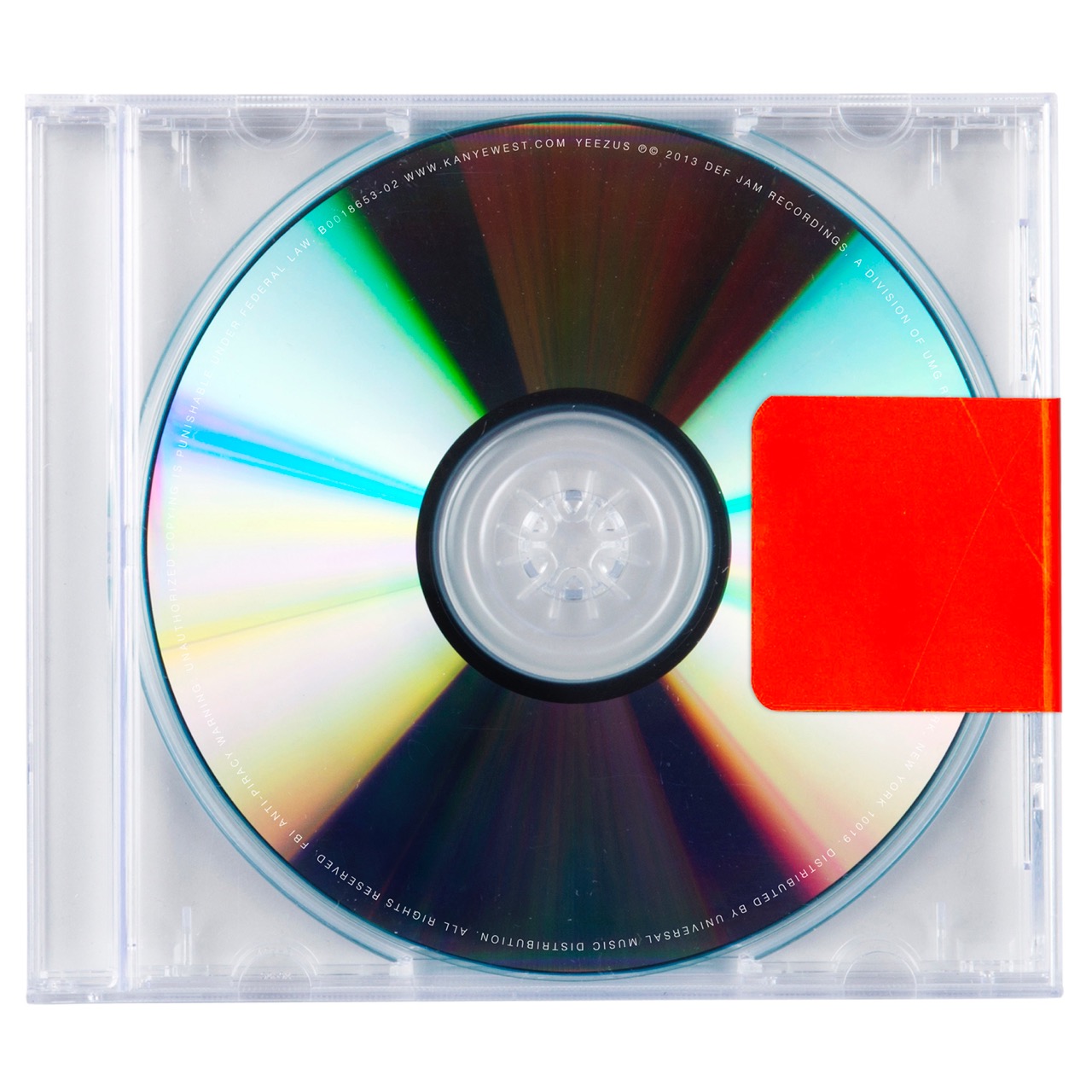

Nearby, a life-size billboard, spray-painted black (Negative Space, 2019), reveals graffiti by the artist when you walk around to look at the opposite side—calling to mind those monochrome Jasper Johns paintings made to look like the backs of picture frames. In an adjacent gallery, viewers encounter Abloh’s package design for two of the most monumental rap albums of the decade, which he art directed as the creative head of DONDA, Kanye West’s design agency. Here, the opulent brass pressing plate from Jay-Z and West’s Watch the Throne (2011) hangs on the wall next to a roped-off, enlarged replica of the blank jewel case that held West’s Yeezus (2013)—the small-pica text of its sample credits made larger than life by the aggrandizing gesture.

Virgil Abloh, Yeezus album art, 2013/19. Image courtesy the artist.

Seeing snippets of art-historical references next to allusions to the porous intersection between sport and rap and “street” culture zooms the audaciousness of Abloh’s enterprise into focus. Virgil Abloh isn’t the first hip-hop artist, but he might be the first hip-hop artist. One can’t look at his designs and not feel the elation of repurposed groove, the wit of a sixteen-bar freestyle, the swagger of Coogi sweaters and Versace shades. But instead of his citations coming from James Brown and George Clinton, he pulls them from Caravaggio and Duchamp. (Abloh calls the latter “my lawyer,” for having established the legal framework that justifies his reinterpretations.)

The implication this has on aesthetics is sizable. The Fear of a Black Planet that Public Enemy prophesied wasn’t just about the literal increase of black people on the Earth. It was cultural—the threat of hip-hop’s reappropriation of the past through sampling just as threatening to the established order as jazz was to classical music, until—alas—jazz and hip-hop developed their own reactionaries. In this light, critics who decry Abloh’s methods of appropriation inevitably recall those critics who supported Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” being taken off the Billboard Country charts, or the fair-weather fans who only listen to “smart” rap. Hip-hop has always been inclusionary; that the gesture has been so flimsily reciprocated does nothing to diminish its exploratory ideals.

Virgil Abloh, look 28, Louis Vuitton men’s collection, spring/summer 2019 (Dark Side of the Rainbow). Photo: Louis Vuitton Malletier / Ludwig Bonnet.

Watching West struggle to be taken seriously in fields outside of music gave Abloh the inside track about what to anticipate from the gatekeepers, and made him work harder to defy them. Yet it isn’t only white assumptions that Abloh is subverting. His refusal to stay in one place cuts against both conservative fashion taste as well as the expectation that a black person raised in Rockford, Illinois, should do something practical. Instead, he takes massive risks on a global stage. In 2017, Louis Vuitton made headlines for having a black model lead the runway show for its women’s collection. Once Abloh took the helm of the menswear collection a year later, he incorporated seventeen, adorning them in designs inspired by The Wizard of Oz and Pink Floyd; his references for Louis Vuitton are just as quarrelsome as anything he has ever deployed—pixelated graphics, stickers inspired by bands on world tour, neon chains resembling either in-store security devices or shackles. Yes, he is one of the first black creative directors of a European fashion house, but he got there on his own terms, which are expansive. His methods advocate for a definition of blackness that is in direct conflict with the stereotypes that hamstrung those who came before him.

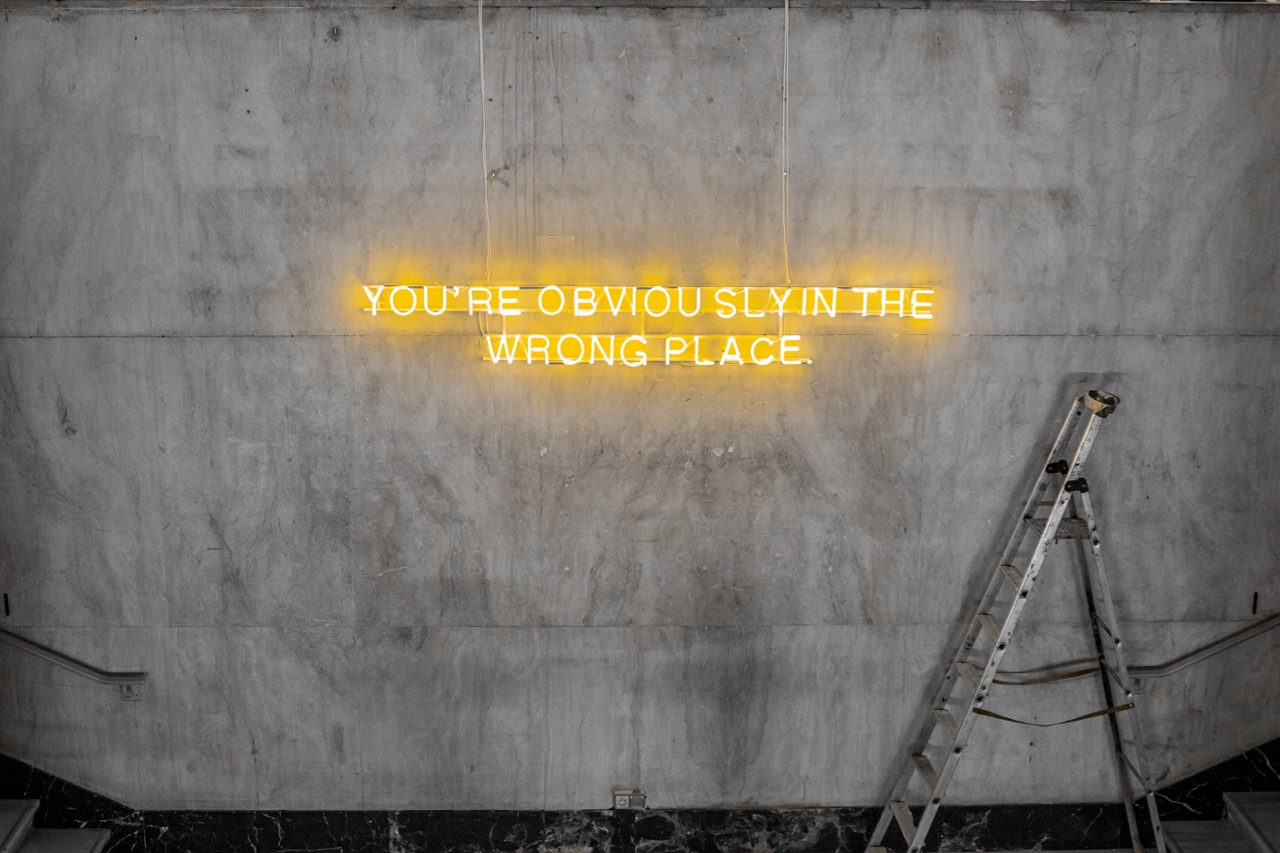

Virgil Abloh, You’re Obviously in the Wrong Place, 2015/19. Image courtesy the artist.

In a discussion with Vestoj editor Anja Aronowsky Cronberg featured in the exhibition catalog, Abloh describes his practice as “throwing a Molotov cocktail at the temple, but in a non-antagonistic way.” It’s difficult to imagine him having it both ways, dutifully patting out a blaze of his own making. But he hopes that his practice is strong enough, his reach wide enough, to counter the status quo without taking an axe to the world that he worked so hard to be a part of. This is a contemporary artist who actually believes his ideas can change things, and these ideas are embedded in his work, ready to engage the viewer, whether they’re a privileged insider or an unruly tourist, like Abloh once was.

J. Howard Rosier lives in Chicago, where he edits the journal Critics’ Union. His writing has appeared in the New Criterion, Kenyon Review, Bookforum, and elsewhere. Rosier is the recipient of the James Nelson Raymond Fellowship from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and an Alan Cheuse Emerging Critics Fellowship from the National Book Critics Circle.