Sukhdev Sandhu

Sukhdev Sandhu

From pipelines to the autobahn: a series looks at how we

reorder the world.

Black Sea Files, by Ursula Biemann. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

“Infrastructure on Film,” Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, New York City, through March 28, 2019

• • •

“Infrastructure” is one of those terms—like “stock indexes,” “Nasdaq composites,” or “the internet”—that tend to induce rapid shut-eye. It’s the deadened language of stuffed-shirt politicos and policy wonks. Yawnsome yakking about diggers and trucks and boring geographies “out there.” It feels like a tarmacadamizing of the imagination. Yet what could be more important than infrastructure? It refers to the process—sometimes shocking—by which things like water and oil and data get to us. It’s the backstory, the secret wiring that underwrites what we think of as reality. It raises profound questions about ecology, economics, global justice. A series on the subject, currently underway at Anthology Film Archives, takes on the challenge of representing what, hidden away beneath the sea or in remote server farms, does not wish to be represented.

The sharpest elaboration of the critical importance of infrastructural aesthetics comes from Swiss filmmaker Ursula Biemann. Black Sea Files (2005) is a split-screen video installation that investigates a topic—Caspian oil geography—that, it’s fair to say, is hardly clickbait friendly or likely to trend on social media. Yet here in often remote parts of Azerbaijan and Turkey is an ongoing battle in which international petrocapitalism wages war against the environment, local sovereignty, and human rights. Biemann, who portrays herself as being on an “undercover mission” and makes telling use of low-key noir music, poses a crucial question: “What will it take to write the hidden matrix of this political space when transnational relations increasingly take place in the invisibility of electronic spaces, off-road terrains, and classified zones?”

Black Sea Files, by Ursula Biemann. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

A partial answer, Black Sea Files suggests, is the emergence of a hybrid figure: a bastard humanist who can marry avant-poetics, radical cartography, image-making, journalism, ethnography, and speculative thought. Biemann becomes a tracker using satellite footage to convey the scale of the extractive operations; a current-affairs reporter as she interviews Kurds who have been expelled from the fringes of Turkish cities and now live in camps next to pipelines; and a kind of transnational diviner as she seeks to uncover what she calls the “transfer of invisible fluids.” She uses language that conjures up science-fiction levels of mutation—piercing, pumping, incision—as she outlines what companies such as BP are doing to the land over which they have dominion. Most of all she teaches us to distrust images of prospering markets: “The relationship between resources, land, and the people is a violent affair,” she insists, “even though the violent relations can look like sometimes peaceful landscapes.”

The Path of Oil, by Bernardo Bertolucci. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

One of the highlights of the Anthology program is Bernardo Bertolucci’s only full-length documentary, The Path of Oil (1967). Funded by Eni, an Italian oil company, and essentially forgotten for the past several decades, it’s a three-part travelogue—a colonial journey in reverse—in which oil is followed from its extraction in Iran to the industrial plants in Ingolstadt, Bavaria. Impelled by a belief that the pipelining of oil was as socially seismic as the arrival of the wheel, gunpowder, and steam, the film is an early and fascinating attempt to find a cinematic language for a topic that many would regard as innately uncinematic.

Bertolucci’s frames of reference are often classical and literary. He likens pipelines to Roman aqueducts, cites the Iranian prophet Zarathustra, and describes desert airline pilots as “romantic characters with their own private mythology and philosophy of life . . . freely adapting childhood adventure stories.” At other times he films sustained conversations with workers who recount whirlwinds dragging down their helicopters or laboring in 122-degree heat. In the third section, set in Europe itself, he creates a character—an aristocratic Argentine journalist named Mario—who pursues the pipes to Germany and is full of wanderlust and reverie, schlepping through snow-caked mountains, reflecting on his own struggle to come up with suitably grand insights. “I dream of myself dreaming new magic images,” he sighs. “ ‘Cinematomagic’ ones . . .”

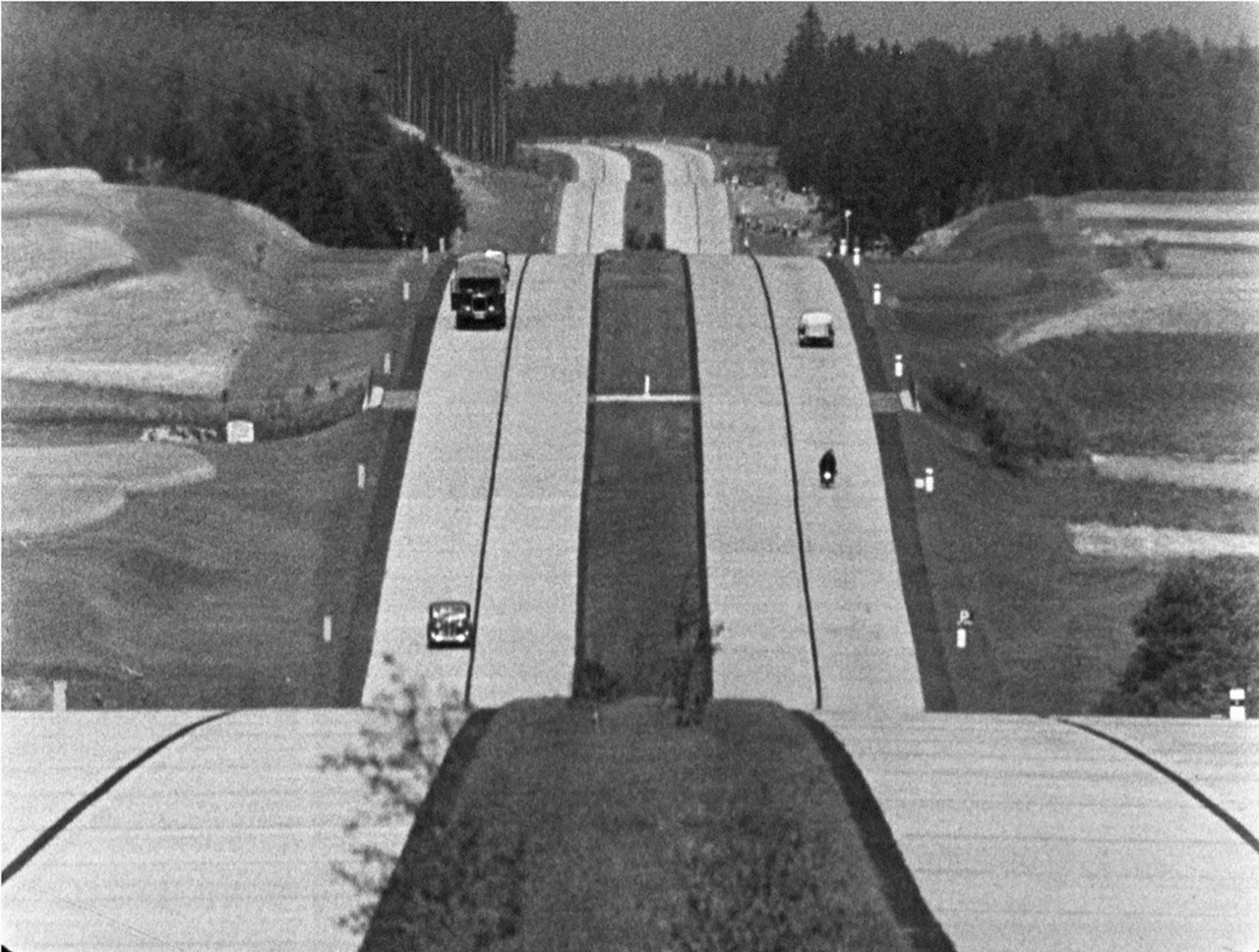

Reichsautobahn, by Hartmut Bitomsky. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Boosting the economy and giving succor to Germans still recovering from World War One privations are the reasons often given for the creation of the autobahn—the huge highway network constructed at Adolf Hitler’s behest in the 1930s. Another perspective is offered in Reichsautobahn (1986) by the brilliant if under-heralded documentarian Hartmut Bitomsky; here the highways represent a form of grandiose land art, a state-sponsored installation designed to ignite imaginations as much as line pockets. “Germany’s biggest edifice,” Bitomsky calls it in his droll voice-over to an archive-rich cine-essay built from propaganda films and photographs whose creative potential was long ignored by artists and historians.

Infrastructure, in Germany then as in wall-torn America today, can be thought of as a symbolic investment. It’s a way to embed politics into the soil, to render a national narrative at the level of geology. According to one commentator in the 1930s, the autobahn, which strengthened ties between north and south, east and west, would bring an “end to petty state particularism.” Hitler saw it as an Übermensch-made landscape, proof of his virile dynamism, a tribute to Teutonic vision. “Where Germany ends,” he declared, “the potholes begin.”

The Land of Wandering Souls, by Rithy Panh. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Perhaps the most emotionally affecting film in the series is Rithy Panh’s The Land of Wandering Souls (2000), which follows a group of Cambodian men and women as they seek to profit from French telecom company Alcatel’s decision to lay fiber-optic cables in southeast Asia. Many come from families terrorized or displaced by the Khmer Rouge. All of them are desperately poor—barely subsisting on fried ants and on tiny crabs extracted from muddy pools, unable to afford shoes as they hack away at the unforgiving earth. Their work is repetitive and badly paid. It’s also dangerous: they find unexploded shells and the bones of Cambodia’s disappeared. One woman’s hand gets horribly infected and distended, but she is unable to afford proper treatment.

Here is the brutal reality that underlies modern-day cant about “seamlessness,” “liquidity,” “immaterial labor.” A foreman in Panh’s film holds up colorful fibers to a worker to demonstrate the magnificence of this undertaking, invoking the fibers’ “magic eyes” and “magic ears”; with them, he says, the worker will be able to see CNN News! Speak to relatives in the US! “I have no electricity,” is the worker’s rueful response. “Only an oil lamp.” CNN would be unlikely to show, as Panh does, a man forced to use his fake leg to chop wood. It wouldn’t dwell on the irony that some of these Cambodians, in toiling to bury cables in the earth, are effectively digging their own graves. You leave the film wanting to ask or to cry out: What would it take for human beings to count as infrastructure?

Sukhdev Sandhu directs the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University. A former Critic of the Year at the British Press Awards, he writes for The Guardian, makes radio documentaries for the BBC, and runs the Texte and Töne publishing imprint.