Sukhdev Sandhu

Sukhdev Sandhu

Coups de foudre: rewatching François Truffaut’s debut feature.

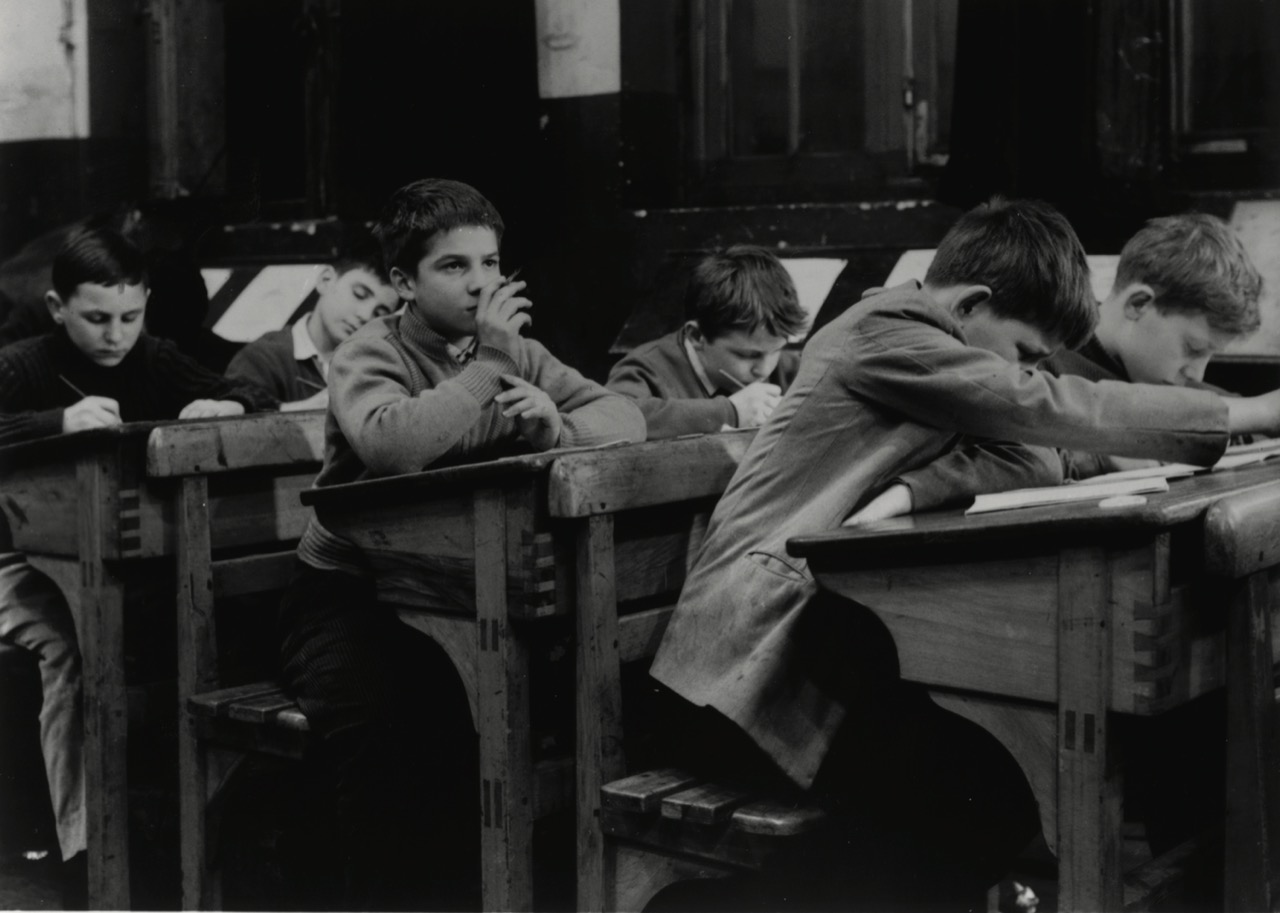

Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel in The 400 Blows. Image courtesy Janus Films.

The 400 Blows, directed by François Truffaut, available to buy or rent on all major streaming platforms

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that most movie theaters around the country remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to revisit films that are particularly significant to them and that are easily found online.

• • •

These past few months, when time has felt out of joint, when the boundaries of day and night have dissolved, when life itself has become slow cinema, my inbox has groaned with movie marvels. Artists have been removing their Vimeo passwords. Galleries that normally act less as gatekeepers and more like bouncers at bottle-service clubs now share the bleeding-edge moving-image work they have financed. Curated channels spring up to broadcast fugitive fare and the militant avant-garde. What booty! Harvest for the cinephile world! Yet why does it also feel so exhausting, a kind of upscale binge-watching? My mind has been drifting away from the present, harking back to the films of my youth, drawn to the fires that started then.

Foremost among them is François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows / Les quatre cents coups (1959), which I first saw during another period of extended lockdown: adolescence. It was a home viewing, since I never went to an actual cinema until my mid-twenties—though I did watch and log many hundreds of movies shown on television. No matter: this—the mid-1980s—was also a time, long gone now, when British schedulers, believing nothing’s too good for the common people, screened foreign and arthouse films by the likes of Fellini, Jarman, and Rohmer in the middle of the evening.

Truffaut had died, aged just fifty-two, in 1984. He was already a legend—the angry young critic (described by a contemporary as “the gravedigger of French cinema”) who had successfully made the transition to making movies, the Bazin-revering exemplar of auteur theory, part of the Nouvelle Vague pantheon. The 400 Blows was his debut feature and follows a troubled teenager, Antoine Doinel (played by newcomer Jean-Pierre Léaud), as he becomes increasingly estranged from the world around him. His relationship with his parents is prickly. His schoolteacher thinks he’s a dunce. He gets caught stealing and is sent off to a detention center.

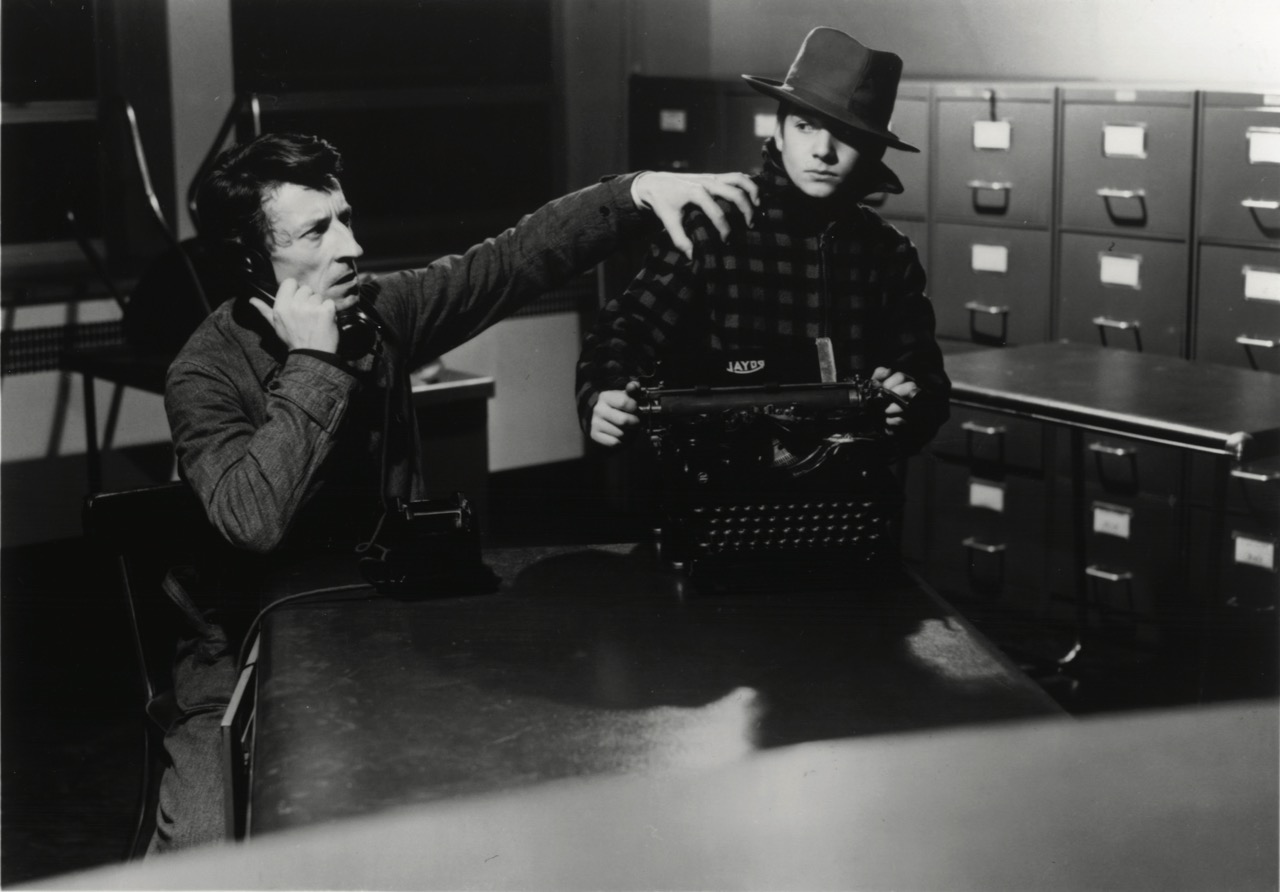

Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel (right) in The 400 Blows. Image courtesy Janus Films.

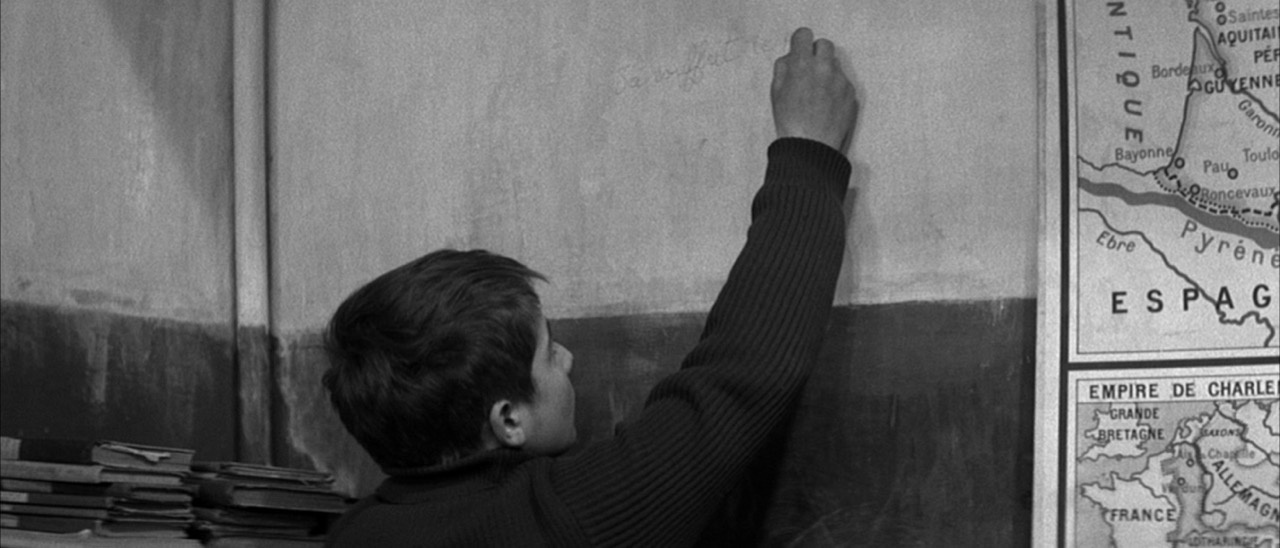

At heart, The 400 Blows, which drew upon Truffaut’s still-raw memories of growing up under German occupation, is a film about freedom—and unfreedom. Antoine is a caged bird. He lives in a cramped apartment with a mother who never wanted to have him in the first place and is at best indifferent to him. The cracked, dirty walls of his classroom are equally carceral; the globe by the teacher’s desk looks unstable; a pinned-up map is dusty and inert. “I’ve never seen the ocean,” Antoine wistfully tells his only friend, René (the charming Patrick Auffay).

Education is also useless to Antoine. The school scenes could be straight out of Dickens. The teachers are grizzled old coves who reduce poetry to a matter of dictation and rote learning. They’re enemies of play, imagination, expansion. Antoine, like Truffaut (who was kicked out of school at fourteen), is in thrall to art and images and literature, but not in any way that the custodians of the curriculum can measure. At home he builds a shrine to Balzac. At school, when asked to write an essay, he doesn’t so much ventriloquize as channel the French novelist. Instead of having his soul saluted, he’s whacked for plagiarism.

Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel in The 400 Blows. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

Children are a minority to which we all once belonged. Truffaut captures with wounding acuity how rarely their hearts and minds are paid attention to by the grown-up world. He’s alert to the whirlpool of feelings, the intensities of emotion, the paradoxes and contradictions of youth. Does Antoine know why he does the things he does? Do any of us at that age? I saw The 400 Blows not long after I watched the installment of Michael Apted’s Up series in which the children he’d started following at the age of seven had turned twenty-eight: it was chilling to learn how many of those kids’ earlier dreams had vanished, how their adult lives had been the unwitting performance of a script predetermined by their class or gender. (Race, too—had the series included more than one nonwhite child.)

Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel, Claire Maurier as Gilberte Doinel, and Albert Rémy as Julien Doinel in The 400 Blows. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

Cinema, for Antoine as for Truffaut, is one of the few places to escape the gray and the grot. It offers fantasy, imagined community, a place less alienating than home. The happiest we see him with his parents is when they all go to a screening of Jacques Rivette’s Paris Belongs to Us. In one unforgettable scene, he rides on a Wheel of Death that resembles a zoetrope: he spins around and around, quicker and quicker, pinned to its wall, defying gravity, superhero for a minute. He has become a film reel. The air is full of screams—of fear, but also of joy. Of letting it out. The noise of his heart.

Paris itself is jailbreak terrain. Antoine and René aim peashooters at pedestrians, steal lobby cards, play pinball, mock priests, skedaddle down the steps outside Montmartre’s Sacré-Coeur church with their arms akimbo. They’re on a spree, in a state of delinquent tremens. Look carefully and you can see a reflection of Roberto Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero (1948), its outdoor locations, its cinema-verité photography. There parentless kids explore the textures of a transformed Berlin, navigate its rubble-strewn streets, treat it as an experimental site.

Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel in The 400 Blows. Image courtesy Janus Films.

The 400 Blows ends with a real jailbreak as Antoine scrambles under a juvenile-center fence and starts running, never once looking back or around him. Past cows and fields and streams. On and on he goes. It seems like he’ll never stop. That’s both a curse—the loneliness of the long-distance runner—and existentially heroic. Finally, he approaches a shoreline. The skin of a nation, the threshold of its identity, where all that is solid becomes liquid. Jean Constantin’s score is beautiful, surging—then plucked, pensive.

Antoine trots toward the water, his back to the camera. Small waves make him retreat a little. He looks toward us. Does he feel trapped? Is this as far as he can go? Or is that—could it be—a look of defiance? Truffaut zooms in on his face. Then: freeze. Fin. It’s a terrifying, exhilarating moment—in 2020 as much as when I first saw it thirty-five years ago and as much as it must have been in 1959. This is the time, it declares. This is the trembling brink. The past—its coldness, its brutalities—has been sloughed off. What now lies ahead?

Sukhdev Sandhu directs the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University. A former Critic of the Year at the British Press Awards, he writes for the Guardian, makes radio documentaries for the BBC, and runs the Texte and Töne publishing imprint.