Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Fortune cookies versus the pandemic: a 1990 piece revived for an

altered world.

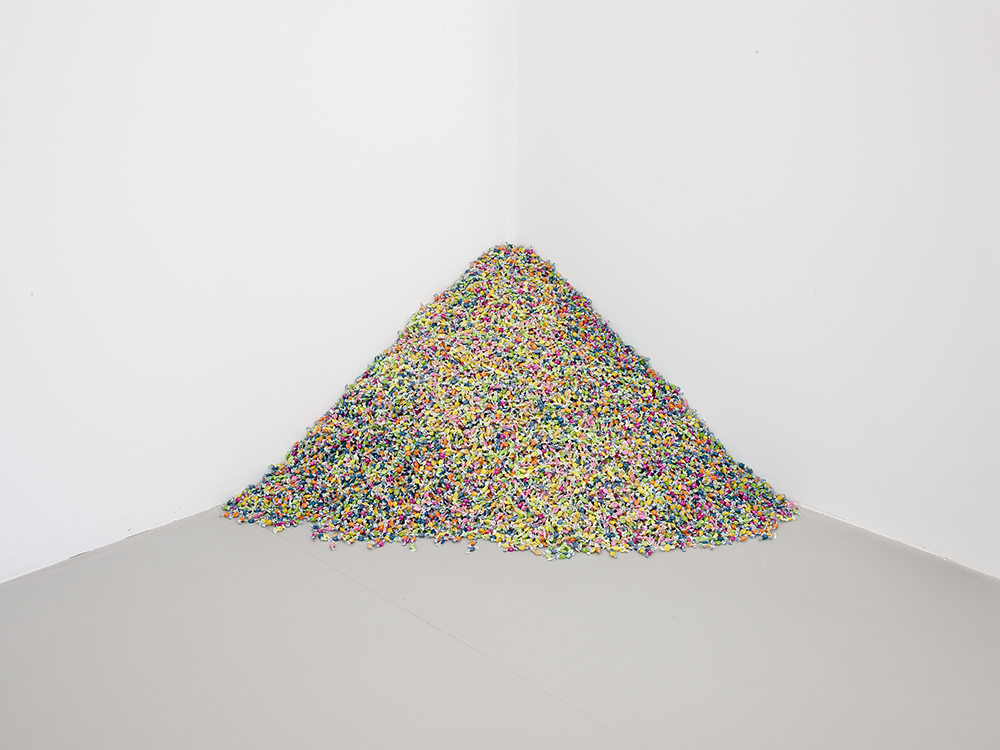

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Fortune Cookie Corner), 1990. As installed by Gary Simmons, garage of a friend’s home, Silver Lake, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Photo: Russell Salmon, May 25, 2020.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres: “Untitled” (Fortune Cookie Corner), presented by Andrea Rosen Gallery and David Zwirner, on view here through

July 5, 2020

• • •

Felix Gonzalez-Torres knew the power of a date to invoke or upset a narrative, to anchor or unmoor history. The zigzagging anti-chronology of his first and best-known billboard work—which was installed near the Stonewall Inn on the Pride parade route in 1989, and reprised last year for the riots’ fiftieth birthday—read, in white type on black, People With AIDS Coalition 1985 Police Harassment 1969 Oscar Wilde 1895 Supreme Court 1986 Harvey Milk 1977 March on Washington 1987 Stonewall Rebellion 1969.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled,” 1989. Billboard, dimensions vary with installation. Installed in the same location as the initial work in Sheridan Square, New York, New York, June 4–July 29, 2019. Sponsored by the Public Art Fund. Photo: Nicholas Knight. © Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Image courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation.

I think about his “dateline” series often these days, wondering what string of things, in what order, might chart the collapsing narrative of right now; or what event the year 2020 might, in the future, summon up first—the pandemic? The mass uprising against anti-Black police tyranny? Whatever unknowable earth-shattering thing comes next?

On May 25, the day George Floyd was murdered, hundreds of irregular golden pyramids, composed of between 240 and 1,000 mass-produced fortune cookies, became—that is, were designated as—Gonzalez-Torres works for the global exhibition of his 1990 “Untitled” (Fortune Cookie Corner). Placed in homes, businesses, museums, or outdoors on grass or pavement, the ephemeral mounds are the latest iterations of his elegiac, participatory candy works. Pieces from the series—which usually lie dormant as sets of semi-flexible instructions—are, when manifested, formed by varying, vast quantities of sweets, meant to be depleted incrementally by viewers and restored to their beginning state during the course of their installation. The glimmering “Untitled” (Ross), for example, from 1991—named for the artist’s partner, Ross Laycock, who died that year from AIDS-related complications—is made of multicolored foil-wrapped candies. It begins at a weight of 175 pounds and disappears, like a body wasting, before it’s replenished. Gonzalez-Torres’s life, too, was cut short, in 1996, at age thirty-eight, by the AIDS epidemic.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Ross), 1991. Candies in variously colored wrappers, endless supply; overall dimensions vary with installation (ideal weight: 175 pounds). Installation view from The Assassination of Leon Trotsky, David Lewis Gallery, New York, New York, September 16–November 4, 2018. © Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Image courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation.

Andrea Rosen, the artist’s close friend and gallerist, curated the exhibition and facilitated the loan of the privately owned “Untitled” Fortune Cookie Corner, and then invited one thousand others to manifest the work as part of a single worldwide site. An email in early May from Rosen and David Zwirner (who co-represent the artist’s estate) outlined the plan and explained that it was initiated in response to “this globally significant moment” (meaning the coronavirus pandemic, presumably) and to publicize the launch of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation’s new website.

As one of the many people invited to stage the work, I thought, reading the press release: How would I get such an unspeakably unessential quantity of cookies? Where would I put them—in my apartment? To eat them anxiously one by one? In order to post pictures on social media? I demurred. But personal skepticism aside, I did think it might be interesting to generate multiple temporary art objects—readymades presented according to simple rules—so we might separately but simultaneously experience, under the conditions of lockdown, an exhibition in real space. It sounded like a potential reprieve from our listless wanderings through online viewing rooms, or like a reprieve in general. And the staging of a Gonzalez-Torres candy work seemed thematically, spiritually apt in a time of such staggering loss; in the face of another virus and a fresh plague of government inaction, incompetence, and uncaring.

On May 25, the screengrabs of the May 24 New York Times front page began to recede. That image, the blanket of capsule obituaries marking the US coronavirus death toll as it passed into six digits—and the (less frequent) rejoinders, showing how the paper of record honored the same tragic milestone for AIDS, the year that Laycock died, with a small L-shaped item on page 18—made way for news from Minneapolis, and then from everywhere. Fortune-cookie stewards around the world began to share photos of their installations, which one can track by following hashtag #fgt🥠exhibition on Instagram, and their posts bobbed, mostly unnoticed, in the flood of astonishing images: protestors taking over highways and bridges, buildings ablaze, shattered storefronts, and memorial portraits of Black lives lost to police violence. On May 27, Larry Kramer, author and righteous, oracular harpy of AIDS activism, died from pneumonia. The fortune cookie emoji, if you looked for it, was often found attached to a shot of an austere gallery space or well-appointed domestic interior, striking a quietly off-key note.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Fortune Cookie Corner), 1990. Preview of installation. Photo: Russell Salmon.

Critic Carolina A. Miranda, in an article for the Los Angeles Times with the title “How a project to honor Felix Gonzalez-Torres devolved into an Instagram stunt,” put it more harshly, noting “the cookies have appeared in lots of tastefully minimal rooms and the account of a dogfluencer. All at a time when the pandemic is exacerbating hunger in the U.S.” She’s right, of course, but I can’t, for myself—as someone who believes Gonzalez-Torres still has something to say, that something might be revealed in the execution of his instructions now—let the project be only a stunt, reduced to a flattened or fun social media presence. Since I personally refused to order a box of cookies to see how the work played out, though, I inevitably find myself scrutinizing Instagram in a strange game of Who Wore It Best. (Documentation of the evolving project is also available on both galleries’ websites.)

I think the artist Gary Simmons is, so far, the winner. Among those who savvily avoided what’s implicitly ridiculous about placing a participatory sculpture in a closed-to-the-public place by selecting a residential sidewalk in Silver Lake, Los Angeles, for his installation, he also added a powerful timestamp. With a simple, perhaps obvious gesture to acknowledge the moment, he provided an intentional context for the Gonzalez-Torres piece, highlighting it not as a blue-chip artwork on loan—which is what a designer chair or a #matthewritchie sculpture seem to do—but as an honest gift. Simmons’s pyramid, pushed against a white single-car garage door, was, by May 31, accompanied by a banner taped above it: JUSTICE FOR GEORGE FLOYD.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Fortune Cookie Corner), 1990. As installed by Gary Simmons, garage of a friend’s home, Silver Lake, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Screenshot of Instagram post. Photo: Russell Salmon, May 31, 2020.

Even on Instagram the scene reads as both memorial and offering; a secular Eucharist dispersing energy and matter into the universe; a metaphor for a single life cruelly snuffed out as well as the systematic winnowing of a community. I don’t think you need to know anything about Gonzalez-Torres to get it. It can be appreciated as a sly infusion of sentiment into a visual language of Minimalist restraint, but—as with all the other successful placements of the work—it also can be understood and enjoyed as profound non-art, just free cookies in a tumultuous time: redistribution.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Fortune Cookie Corner), 1990. As installed by Gary Simmons, garage of a friend’s home, Silver Lake, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Photo: Russell Salmon, June 5, 2020.

As of this writing, the first banner has been replaced by a sturdier one fastened to the doorframe at each corner. Carefully hand-painted black letters on unprimed canvas read BLACK LIVES MATTER. A ubiquitous, unrarefied message of the utmost importance, it brings the sculpture below it to life, once again, as something urgently, rather than pristinely, elegant. It seems an effortless, aptly absurd connecting of dots, and maybe of dates—from 1990 to 2020, or between various days in a single epochal late May.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.