Yasmine Seale

Yasmine Seale

The poet Salim Barakat receives his first English translation.

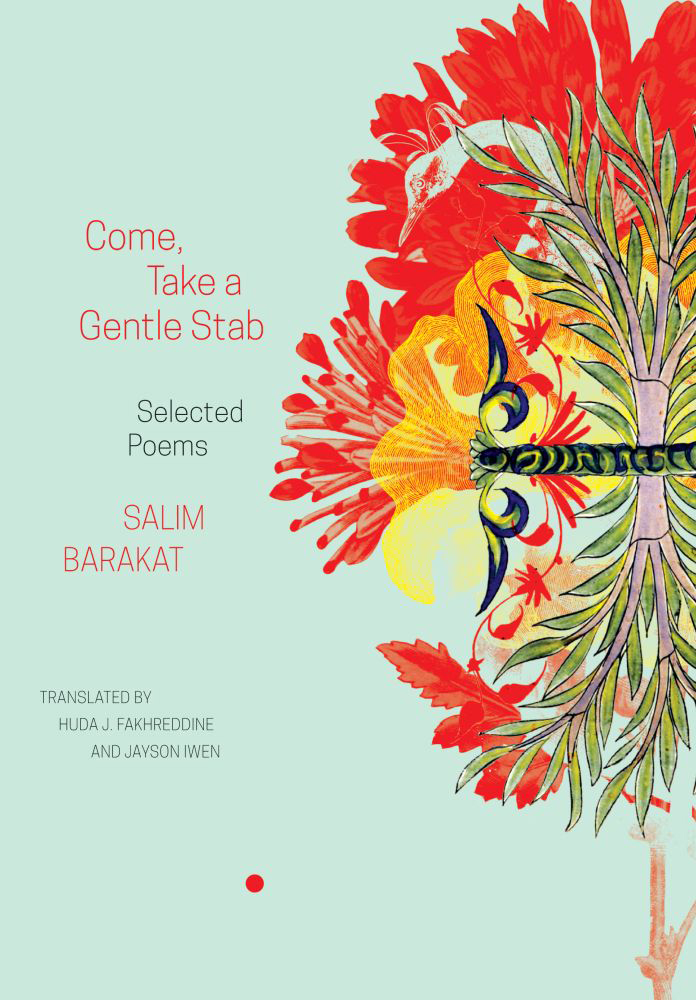

Come, Take a Gentle Stab, by Salim Barakat, translated by

Huda Fakhreddine and Jayson Iwen, Seagull Books, 95 pages, $19

• • •

Kurdish, reclusive, demanding, inventive to the point of miracle, prolific to the point of cataracts—in the republic of Arabic letters, Salim Barakat stands apart. He fascinates his peers and readers for the same reasons, I would guess, that he is barely known in English: the granite difficulty of the work, its baroque range. It represents no one and teaches nothing but its own wild arithmetic, far from the reach of commentary or schools. It does not sit well with “Middle East Studies.”

Barakat was born in Qamishli, northern Syria, in 1951. As a young man he moved to Damascus but couldn’t live there, with “the smell of police” all around. He left the country at twenty and has never returned. After a spell in Beirut and over a decade in Cyprus, he settled in a forest outside Stockholm. His fifty-eight books of poetry and prose span multitudes but have in common a tricksy, adversarial approach to Arabic, his second tongue—what the translator Huda Fakhreddine has described as “language intentionally textured and thickened beyond recognition.”

Of his experiments in prose, a partial view: two memoirs of boyhood; two fables about a kingdom of cave-dwelling centaurs, their dreams, and their paranoid tyrant; an abstract novel on the Lebanese civil war; a five-hundred-page novel involving jinn; a five-hundred-page novel involving Zenobia, queen of Palmyra; a book about a cruise ship looking for mermaids; a book about kisses. One novel is set in the twelfth century. Most rebel against the laws of time and place, wandering, as the writer Juan Goytisolo put it, “in a kind of visionary geography.” Around the turn of the century Barakat published three dense novels he calls his “cathedrals,” so complex that his Swedish translator, after working at one of them on and off for seven years, finally gave up.

So much for the straightforward part. Prose is a system, Barakat has said—a contract. Poetry, on the other hand, is meaningless if it does not seek to break the agreement, to undermine the settlement we call language. His poems, often composed of obsolete words in incongruous relation, almost defy translation. Come, Take a Gentle Stab is the collaborative effort of Fakhreddine, a scholar of Arabic poetry and champion of its more challenging practitioners, and the poet Jayson Iwen. It selects from eight collections—a fraction of Barakat’s poetic output—and whets the desire for more. As the first book of his work to appear in English, it sets a perilous hurdle and vaults it. It is a remarkable feat.

The title poem, which opens the volume, contains an image of lungs set ablaze. We are in a fever dream of hyacinth and battle dust, Byzantine capitals, “alembics of blasphemy.” There is an atmosphere of mythology that may only be the gold of memory. “You shall see my blood / swamped with sea kings and city brick.” A verse retelling of a Kurdish love epic, “Dylana and Diram,” might also be read as a call to sharpen experience through language refreshed; several sections begin with the word “wake.” This is poetry as apocalypse, in its first sense: the uncovering by verbal means of secret knowledge.

Down the decades a voice emerges, unmistakable—proud and oracular, open to the broken world, calling it to him, threatening “those who come to me unified.” Imperatives are hitched to impossibilities, non sequiturs fervently pursued. Posterity is simultaneously courted and mocked: in 1982, “chew eternity with chainsaw teeth”; in 1996, “lower your voice when you address Tomorrow.” The poems gesture at their own virtuosity, a mirror to the drunken variety of things: “Untranslatable gazelles and yet I translate them.” They fling out startling images and retract them, contradict themselves, full of urgency and full of questions. They are not grandiose for very long. “Do I cry: A horizon? No.”

For all its fabled obscurity, the writing here is also congenial, even comradely. Some avant-gardes make a point of leaving the reader trailing behind. Barakat’s puzzles invite us in, ask us to give more of ourselves. “Stare at me as befits an enemy, then empty your pockets on the table. First, the garden. I see roots poking from your shirt. I see dirt on your hands. Come, put it all on the table . . . the garden first.” One poem addresses death like a neighbor: “Blow the horn of your little truck every time you pass on the road to your errands.” Many glow with creaturely warmth. “Ran’s Farm” is a conference of birds in the deep north (to the hoopoe: “Gather adversities like fluff / and sing the journey into a slow bleed”) and there are snippets of a book-length bestiary. Even cerebral, even disjointed, these poems feel earthed to a world more immediate and tender than poetry. They sing the body’s secret life beyond all metaphysics. “You, desirable, woven by darkness, where do you go, delicious one?”

“Poetry,” Barakat has said in an interview, “is a chaos ‘committed’ to the ethics of magic.” The word “committed” (multazima in Arabic) appears between quotation marks. Used like this, turned from its usual sense of political engagement, it is piquant. Barakat has always stood at an angle to the struggles of his generation. His writing, probing as it does the collective unconscious of his people, does not so much describe or denounce violence as embody it.

At the shattered heart of this volume is a section from Syria (2015), a reckoning with the destruction of his native country in a war that has produced “no victor but howling.” The poem begins exhausted: “Don’t ask me to master discipline, to master precision from now on.” Here we are taking stock after calamity. The apocalypse has landed and brought no revelation, only silence and a painful disillusion. “No proof of the sky, after this. No proof of a ladder to it, no ladder to descend from it to the human, O Country.”

What is there to say about these poems that largely escape sense and make so much happen? They take refuge in a long history of song (“that delicate line, running from the origin of comedy to your moan”) and summon us to join them. This translation is most alluring where it gives form to Barakat’s philosophy, a poetics of damage that is always available to the consolations of sonic relief. Try rolling these lines around your mouth—“let it be slow, your enchantment / of the chambers of her heart”; “like muscles your destinations slackened, and you sagged”—and see if you are not, in your brokenness, gently calmed.

Yasmine Seale is a writer living in Paris. Her essays, poetry, visual art, and translations from Arabic and French have appeared widely.