Yasmine Seale

Yasmine Seale

A new Rumi translation steers clear of gurudom for a poetics divine

and earthly.

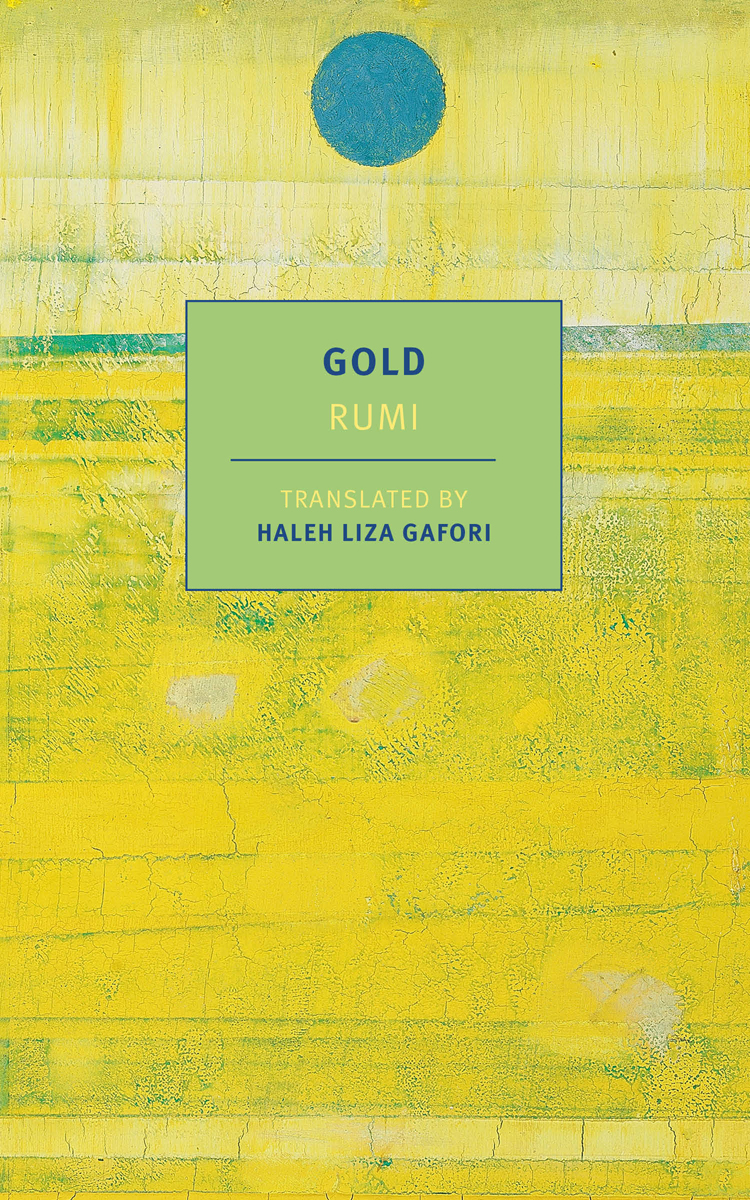

Gold, by Rumi, translated by Haleh Liza Gafori, New York Review Books, 87 pages, $14.95

• • •

Rumi was born in what is now Afghanistan, in 1207, to a world about to be destroyed. A few months earlier, a few months ride due east, a tribal chief had taken the title Genghis Khan—“universal ruler”—and, having subdued the nomads of Mongolia, turned his designs on everyone else. Reports of ruthless horseback armies closing in across the steppe sent Rumi’s family west. For two decades they drifted, just ahead of the hordes; by the time they settled in Konya, at the far limit of the continent, the grand cities of Rumi’s childhood lay in ruins—Samarkand, Nishapur, his own hometown of Balkh. His father, a Muslim theologian, had named him Jalal ad-Din, “splendor of the faith.” We know him as Rumi because of where he found safety: Rum, the region of Anatolia, where the sultan welcomed refugees.

Displacement across Asia was only the first of his life’s dizzying swerves. In Konya he took over his father’s teaching post, preaching to thousands. His son and biographer tells us that during this period, Rumi would pray for his life to be changed by one of God’s hidden saints. In his late thirties, his prayer was answered. A wild-looking, freethinking dervish known as Shams arrived in town. Rumi later wrote that before this meeting, “I was raw.” The encounter cooked him. For two years they were inseparable, absorbed in a mission of transformation Shams called “the work.” He once barged in on Rumi bent over his books and shouted, “Don’t read! Don’t read! Don’t read!” The keys to a freer existence lay elsewhere: in music and dance; in the shedding of convention; in plain, vulnerable speech. The ascetic scholar became, his son wrote, “drunk with love.” Then, as suddenly as he had appeared, Shams vanished—possibly killed by Rumi’s jealous pupils.

What had been cooked now burned. The great traveller Ibn Battuta, passing through Konya decades after Rumi’s death, still heard stories of his grief: “he had become demented and would speak only in Persian rhymed couplets which no one could understand . . . His disciples used to follow him and write down that poetry as it issued from him.” The torrent flowed for thirty years until his death. To the pace of drums and reed pipes he would whirl, hour after hour, molding passionate utterance into ghazals. Later in life he began his monument, a strange didactic poem called simply Masnavi, or “Couplets,” which ran to six volumes. Steeped in the Quran, it has been revered continuously wherever Persian is understood. A fifteenth-century historian reports that even Hindu brahmins in Bengal recited it.

Gold selects not from that sober, mature work but from the lyric reveries of Rumi’s metamorphosis, the fruit of altered states. Here, writes Haleh Liza Gafori in the preface to her translation, the poet speaks “as humble seeker, demanding sage, kind elder, and ravaged, ecstatic lover.” Medieval compilers of Rumi’s verse tended to arrange it alphabetically according to rhyme. Gafori works in another tradition, picking and juxtaposing sprigs of language until, as one poem has it, they “unfurl a honeyed musk.” Rhythmic, intuitive arrangements revive the conditions in which this poetry came into being. An early meaning of translation was the movement of a saint’s body from one place to another. Through these outbursts, these notes from the edge of sense (“Every what and why dissolved like salt”), we are drawn into the dance. We hear “the ruckus the muse makes.”

Rumi envisioned scripture as a rich fabric woven on two sides: “Some enjoy the one side, some the other. Both are true.” His poems, like velvet, are shimmering or rough depending on your view; they speak of both heaven and earth. Mystical ideas are wrapped in the stock images of Persian love poetry—eyelashes, cupbearers, nightingales. Objects of everyday life become channels to the divine. A sixteenth-century miniature depicts dogs in a market listening to Rumi; his teachings, however abstract, feed on the boisterous, edible world. The unity of creation, a constant theme, is like “one oil in countless almonds.” Transcendence begins here and now; it smells of basil, of tripe.

The wealth of sensual metaphors in Sufi poetry has compelled some translators to choose a side of the fabric. A. J. Arberry, who also produced an English Quran, made Rumi’s intoxicated odes sound like hymns. The dancing limbs are clothed in fustian; the Persian word for a hangover, khumaar, becomes, coyly, “crop-sickness.” Coleman Barks, who since the 1980s has turned Rumi into America’s favorite guru, sought to “free his text into its essence” by shaking the ghazals loose of their religious content, and sometimes altogether of their meaning. Gold steers between these rocks: here is a supple, intimate idiom still anchored to the sacred, a poetics of arousal that puts “mystery in the middle.”

When Rumi died, in 1273, everyone in town attended the funeral—Christians, Muslims, and Jews. A Greek priest said, “He was like bread.” Lifelong exposure to other faiths and languages helped give new shapes to his own. The story goes that when a seller of fox skins passed by his house, the Turkish cry for fox Tilkü! Tilkü! inspired Rumi to compose the line Dil koo? Dil koo? “Where is the heart? Where is the heart?” In the serene grandeur of these poems (“I rise like smoke”) there are traces of the Central Asian melting pot he left behind: Buddhist renunciation, Zoroastrian fire. From a life winnowed by loss he forged a voice that called across boundaries; the oneness of things might be consolation for their impermanence.

Every age invents its own past; each translation, however rigorous, is also a self-portrait. Hegel saw in “the excellent Rumi” a model of pantheistic thought, a mirror to his own philosophy. Arberry’s ghazals (and those of his teacher, Reynold Nicholson) unwittingly have the chilly, formal air of the Cambridge rooms in which they were made. Gafori writes that she chose poems that “speak to our times” and, in some cases, proposes a new reading. Beneath the gorgeous imagery, there are hard questions about how to live in times of crisis. “Whatever the ways of the world, / what fruits do you bring?” (Barks’s version of the line, by contrast, exhorts withdrawal: “What happens in the world, what business is that of yours?”) Far from new-age quietism, these poems urge the heart to be alert, amazed, to meet the “sour world” awake. “You have a role at this feast. Rise up.”

Yasmine Seale is a writer and translator living in Paris.