Yasmine Seale

Yasmine Seale

Power to the people: a new restoration of Sarah Maldoror’s masterpiece of anti-colonial cinema.

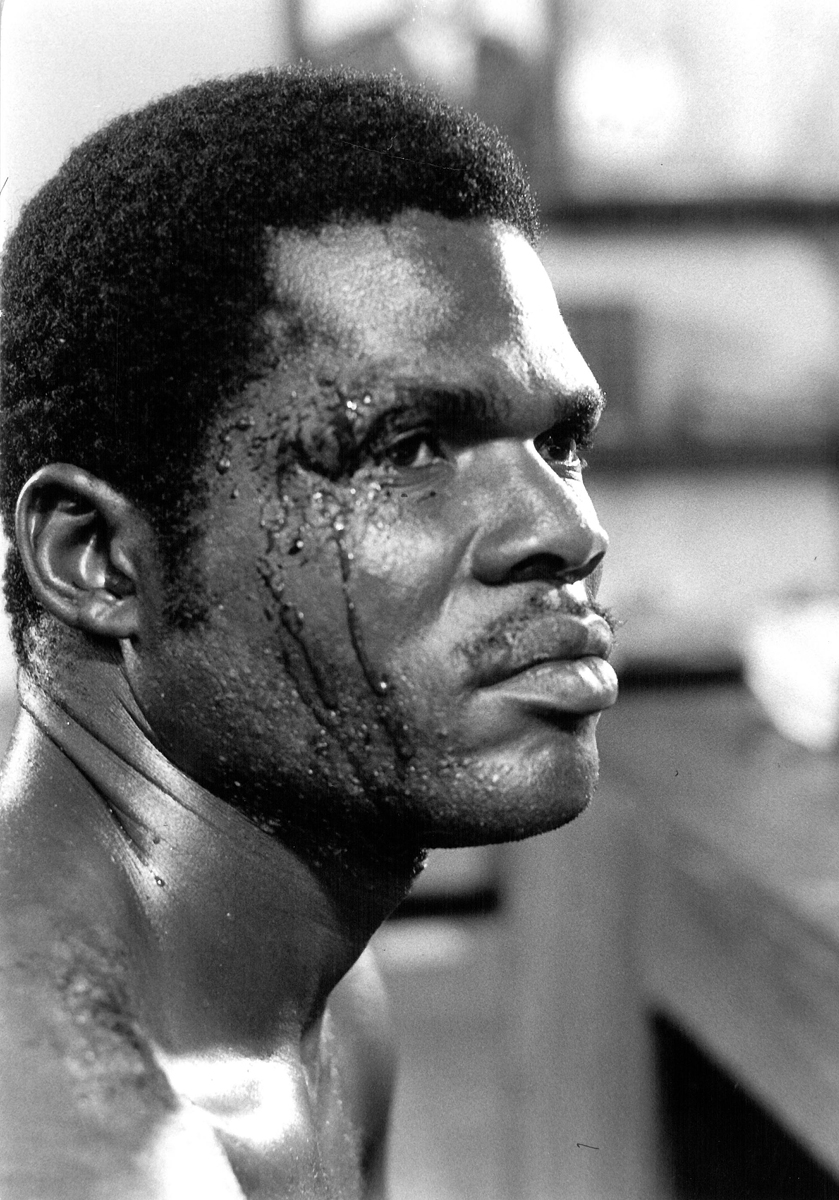

Manuel Videira as PIDE agent and Domingos de Oliveira as Domingos Xavier in Sambizanga. Courtesy Cinemateca di Bologna and Film Foundation. © Suzanne Lipinska.

Sambizanga, directed by Sarah Maldoror, screened as part of Sarah Maldoror: Tricontinental Cinema, Palais de Tokyo, 13 avenue du Président Wilson, Paris, through March 13, 2022; also screening at the Walker Art Center, 725 Vineland Place, Minneapolis, February 25–26, 2022; the Wexner Center for the Arts, 1871 North High Street, Columbus, February 26, 2022; the Dublin International Film Festival, February 28, 2022; and at the Swedish Film Institute, Filmhuset, Borgvägen 1-5, Stockholm,

March 3, 2022

• • •

In the 1950s, tired of being cast as maids, four friends founded the first all-black theater company in France. One of them was Sarah Maldoror, who went on to study at the Moscow Film School and to work (uncredited) as an assistant on The Battle of Algiers (1966). The camera became her traveling eye, the weapon of her fierce commitments. Though more immediate and more portable than the stage, it had obstacles of its own. She completed over forty film projects—features, documentaries, many shorts—and left at least as many unrealized. Those that did get made suffered damage and loss. Sambizanga, her 1972 masterpiece on the Angolan liberation movement and the first feature film shot in Africa by a woman of African descent, slipped out of her control. The rights were sold by one French producer to another, who held them hostage for decades. Neglected, unseen, the film was left to fade. After a long battle waged by Maldoror’s daughters with support from the Film Foundation, it has been restored to radiance. A screening in Paris this past autumn felt electric, rare—like seeing kingfishers.

An artist of playful and poetic disposition, Maldoror (1929–2020) devoted much of her work to anti-colonial struggles. She would not have seen a contradiction, perhaps not even a distinction, there. Her lifelong subject was the hunger of the spirit to get free. Sambizanga begins with water foaming, surging, crashing against rocks only to rise again. The year is 1961. Domingos Xavier (Domingos de Oliveira) works as a tractor driver in a quarry; by night, unbeknown to his wife, Maria (Elisa Andrade), he distributes leaflets against Portuguese exploitation—against the forced labor he performs by day. Thirteen minutes in, he is bundled into a car and driven away. What follows are three braided plots: Domingos’s martyrdom as he is imprisoned, tortured, and finally killed; Maria’s quest to find him; the efforts of the underground resistance (the nascent People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola, or MPLA) to identify the prisoner and send him courage.

A kidnapping and the ensuing search might have yielded, in another director’s hands, a frantic, breathless thing. Sambizanga takes its languid time. It is a film, partly, about pace: the contrapuntal rhythms of political awakening, the basic difficulty of obtaining information and transmitting it. Characters are forever searching for the right person to talk to, then the right place to talk to them. We are shown how knowledge of brutality seeps through a population and is managed: from collaboration to obliviousness through subtle sabotage. A guard smuggles Domingos a note, which he swallows, telling him not to lose heart.

Elisa Andrade as Maria in Sambizanga. Courtesy Cinemateca di Bologna and Film Foundation. © Suzanne Lipinska.

We see, more simply, how long it takes to walk anywhere. Maria—played by Andrade, a Cape Verdean economist, with magnetic self-possession—strides across blue hills from town to town, her baby on her back and questions in her eyes, enduring the flirtations and the cruelty of bureaucrats and, worse, their indifference. It is the journey of her own coming to consciousness. A mourning song of aching tenderness escorts her on her trek. We hear it again on her bus ride to the capital, which is laced with shots of Domingos and his cellmates circling the jail yard. That scene’s composition recalls Van Gogh’s picture of carceral despair, Prisoners’ Round (1890), which hangs in Moscow and which Maldoror, a great lover of painting, may well have seen there.

On his last day of freedom, Domingos turns to his wife, who is being quiet: “Maria, que contas?” What’s up? But also: What story do you tell? (The actors, all nonprofessionals, speak in their own language: Lingala, Kimbundu, Portuguese.) Maldoror was always attentive to the stories women tell—sometimes at great cost to her. She was living in Algeria when, in 1970, she made her first attempt at a feature. Des fusils pour Banta, shot in Guinea-Bissau three years before independence, followed a young woman who joins the local guerrillas. The postcolonial Algerian authorities, who had commissioned the film in their zeal to promote struggles kindred to their own, disliked its feminist angle and confiscated Maldoror’s six reels of footage. She had to leave the country. The reels have never been found.

Though she depended for support on the liberation movements she espoused (her husband and occasional cowriter, the Angolan poet Mário Pinto de Andrade, helped found the MPLA), Maldoror would not make propaganda. Sambizanga is about the hardest things, but it leaves a gentle, almost honeyed flavor in its wake. Its slyest move is to show political abstractions entangled in material life. When revolution is being pondered there are lullabies to sing and lunch to make: details, warm and inconvenient, in the tapestry. The women who dot the film to ease Maria’s way—providing her with guidance, comfort, food, shelter, song—model collective responsibility without the need to spell it out. Poetics of relation are not theorized but brightly lived.

Such subtle treatment is all the more remarkable as Maldoror was working in the heat of insurgency; her friend Amilcar Cabral, another founding member of the MPLA, was assassinated a few months after Sambizanga won the Tanit d’Or at the Carthage Film Festival—a prize named after a warrior goddess. In the movie’s final minutes we are back in the quarry, not to work but to chip away at the larger edifice. News of Domingos’s death precipitates a plan among the rebels to raid the colonial prison in Luanda. The date they set—February 4, the last thing we hear before we are returned to surging water and the credits—marks the beginning of the long war of independence, achieved in 1975. Earlier, an administrator had complained to Maria of the oppressive heat. Sambizanga is a study of gathering clouds: the calm before the storming of the gates.

Domingos de Oliveira as Domingos Xavier in Sambizanga. Courtesy Cinemateca di Bologna and Film Foundation. © Suzanne Lipinska.

What looks prophetic is in fact a kind of ultrasound, a real-time view of events before they are birthed into history. Sambizanga was adapted from a novella by Luandino Vieira, the son of white settlers in Angola who became active against colonial rule (he took the name Luandino out of kinship with the poor multiracial neighborhood of Luanda where he grew up). He completed the story in 1961, only days before he was captured by the Portuguese secret police and sentenced by a military court to fourteen years in prison. Domingos’s arrest at a dam construction site mirrors Vieira’s own experience, and what his interrogators most want to know is the name of the white man helping him. The deepest threat to power is not sedition but solidarity: the idea that a movement might be broadened, community chosen, that one group’s plight might be everyone’s concern.

Maldoror’s own interest in pan-African emancipation was one of affinity rather than origin: born and raised in southwest France, she barely knew her father, much less his native island of Marie-Galante, near Guadeloupe. “I am from where I am,” she liked to say. To her polymorphous mind, the riotously plural world was home. Self-determination involved, to an extent, self-fashioning—the freedom to choose which mask to wear. She made three films about carnivals and borrowed her surname from the demonic hero of a nineteenth-century prose poem. “No nation but the imagination”: Derek Walcott’s line might have been hers.

Yasmine Seale is a writer living in Paris. Her essays, poetry, visual art, and translations from Arabic and French have appeared widely.