Helen Shaw

Helen Shaw

To thine own hoodie be true: Oscar Isaac and Sam Gold bring slacker-chic to Elsinore.

Peter Friedman and Oscar Isaac in Hamlet. Photo: Carol Rosegg.

Hamlet, by William Shakespeare, directed by Sam Gold, The Public Theater, 425 Lafayette, New York City, through September 3, 2017

• • •

Actor Oscar Isaac (Inside Llewyn Davis, a little movie called Star Wars: The Force Awakens) is a big enough deal that if he wants to be Hamlet, he’s going to be Hamlet. His Juilliard schoolmate Sam Gold—a Tony Award–winning director whose last two shows starred Sally Field and Daniel Craig—can also do whatever he bloody likes. And what they wanted to do, after talking about it on and off for a decade, was to turn Hamlet the Dane into Hamlet the Guy.

Their often frustrating, sometimes illuminating Hamlet—now at the Public Theater—has the hallmarks of a typical Gold production. He stages plays in barebones interiors, spaces that look like bunkers or rec rooms or empty stages set up for rehearsal. When he directs revivals, he strips out all markers of a piece’s original era and milieu, changing any period paradigm into the current moment. In Hamlet, for instance, when Ophelia (Gayle Rankin) gets stressed, she rips into a catering tray of lasagna; Hamlet’s “inky cloak” is a sweatshirt; we see Polonius (Peter Friedman) conducting business on the john. And there’s usually a deliberate staginess too—actors stick around to watch one another’s scenes, which can give even frantic scenes a kind of lounging, desultory vibe.

Oscar Isaac and Keegan-Michael Key (foreground), and Peter Friedman and Gayle Rankin in Hamlet. Photo: Carol Rosegg.

At the Public, this oh-you-just-stumbled-into-our-run-through aesthetic means Kaye Voyce’s costumes could almost be the company’s street clothes, and props are greenroom detritus like plastic cups and crummy folding tables. Never mistake Goldianism for Poor Theater, though. It’s slacker-chic, expensively realized. In David Zinn’s red-carpeted set, no penny has been spared to erect a wall that looks like (but is not exactly) the back wall of the theater. Hamlet obsesses over the tension between seeming and being, and so it’s appropriate that Zinn’s design seems like a non-design but is a construction full of decision and affectation.

As in Gold’s other productions, the effect of this fashionable modernity isn’t cool, exactly. Rather, it manifests a bone-deep chill. Characters seem trapped in an airless limbo; the banality of “now” drops a damping, even suffocating blanket over the play’s action. This may be why Gold’s style works best for claustrophobic stories of oppression and escape. It worked in Annie Baker’s Pulitzer Prize–winning The Flick (a desert-dry work-is-hell comedy), not to mention his superb The Glass Menagerie, which was recently on Broadway. But in Hamlet? Oh, my divided soul! As a total system, this Hamlet keeps breaking, right along the dotted line between broad-brush hipsterism and intelligent economy.

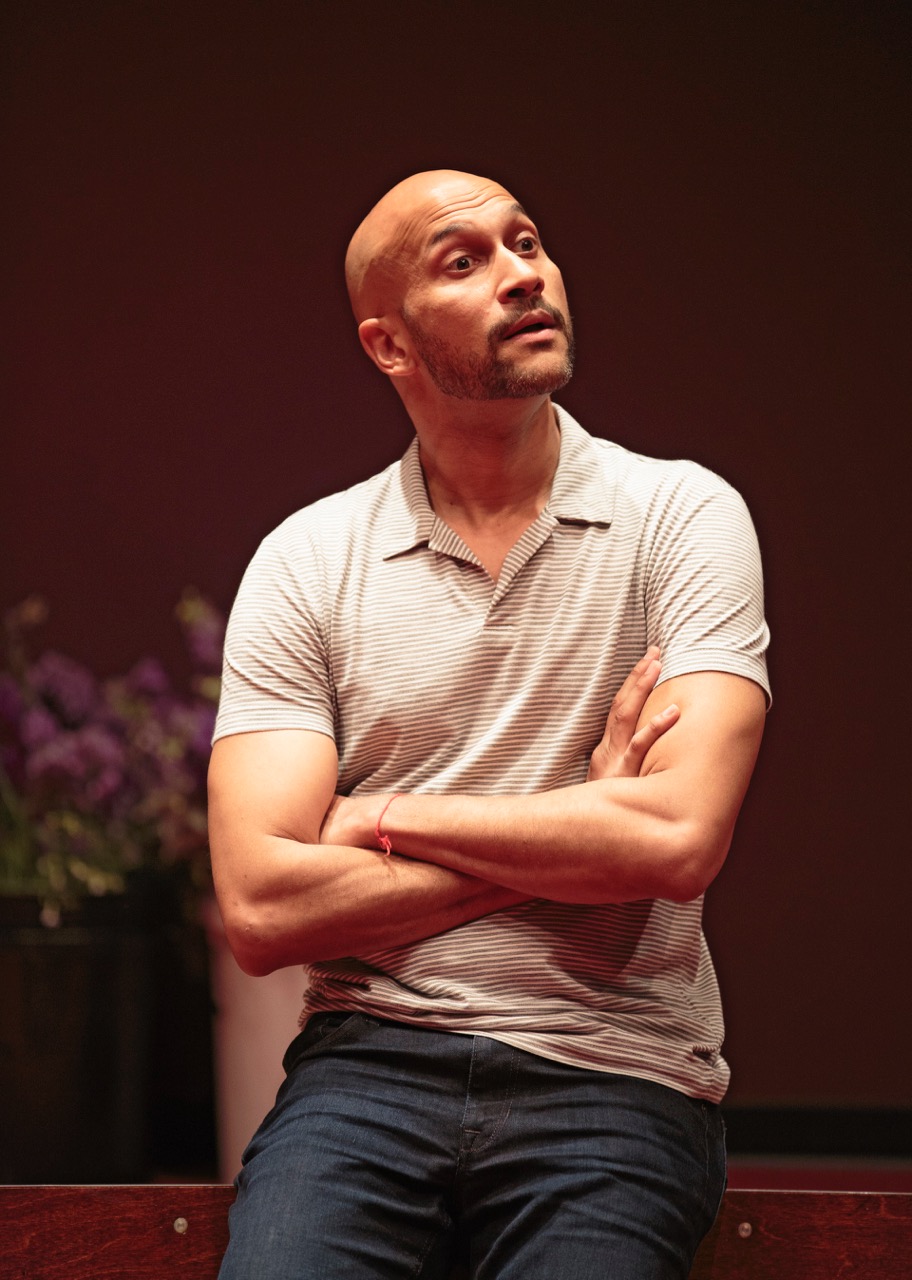

Keegan-Michael Key in Hamlet. Photo credit: Carol Rosegg.

What we gain from a hoodie Hamlet is intimacy. Keegan-Michael Key, brilliantly playing Horatio as Wittenberg’s class clown, introduces the show with a hey-how-ya-doin’ bit of crowd work, softening the edge of the monument we’ve geared up to see. No one onstage or off has time to be intimidated by this Colossus of all Drama: the idea of “Shakespeare, our contemporary” is well served. The thing we lose, though, is scope. We even lose meaning. For Gold and Isaac, the play is centrally about a grief-struck everyman, one essentially like us. So when Hamlet pretends to be mad (Isaac just takes off his pants), he never feels that threatening; when he rejects Ophelia, it seems more a bad breakup than an existential earthquake. You also wouldn’t know from this Fortinbras-free version that we’re watching a state topple. Outside the play’s Elsinore, armies massed, rebellions loomed. Not here. This renders the political lines—Hamlet claims Claudius frustrated his “hopes” of rule—as near-nonsense.

Gold’s production runs the full spectrum from sophomoric (the silly substitution of a plastic syringe for a sword in most of the murders) to deft (how triple-cast actors un-fussily dump one persona and assume another). For many of the actors, the best of these choices create good work. As Gertrude, Charlayne Woodard finds lovely details; Anatol Yusef does a speech as the Player that runs rings around the stars nearby. But Friedman’s Polonius is the play’s most shining instance: a funny fusspot whose every word seems to be springing, new-formed, out of his busy little brain. Gold does his best staging with him too. After Polonius is murdered, he’s dragged center stage. Distraught Ophelia piles earth on him, then snuggles down beside her father. And then—only a few beats later—the pair bounce up out of the dirt as the comic gravediggers. That’s Hamlet! That’s its theme, its heartbreak, and its black comedy all in one image. Bounded in a nutshell, indeed.

But Gold fails his sweet Prince, and, in the end, Hamlet is Hamlet. For instance, in his most consequential staging choice, Gold has usurping uncle Claudius (the lizardy Ritchie Coster) also play the ghost of Hamlet’s dead father. This idea seems radical at first, but it means less—and undermines Isaac more—each time we return to it. The text, full of emphatic contrasts between the old King and new, fights the double-casting at every turn. And it means Hamlet is now beset by a greatest enemy who keeps phase-shifting into his greatest love. This could be enormously interesting—if Gold and Isaac were able to work this into a coherent portrait of the doubt-wracked Prince. No such cohesion appears. Emotion becomes dangerously general.

Oscar Isaac in Hamlet. Photo: Carol Rosegg.

Certainly, Isaac has the tools. Kenneth Tynan said that Laurence Olivier was great (in part) because of his huge tiger’s eyes, which were “readable” from anywhere in the theater. Isaac has ’em too—big, deep-socketed, melting eyes with a wary forest gleam. (Unfortunately and irritatingly, Mark Barton’s lighting design is so down-lit, audience back of the fifth row can’t always see them during soliloquies.) And Isaac does act with beautifully spoken clarity. He uses verse confidently, the meter handled with an easy hand. In the gravedigger scene, he’s as charismatic as any Hamlet I’ve ever seen—so laughing and sweet with the indispensable Key, so open about his affection for poor dead Yorick, that we understand how difficult violence might be for such a man.

Yet there should be more than ease and clarity. All these interactions and dithering soliloquies must add up, must show us the inexorable math by which Hamlet calculates his fate. Gold’s production solves each scene separately with little connectivity to what’s on either side, so while Isaac quakes with emotion in moments of crisis, the show winds up feeling like a series of set-pieces rather than a journey. Crucially in a play about decision itself, there’s no sense of development, nor of the way thought moves in this most inward man. (Development is an Achilles heel for Gold; his recent Othello had the same trouble.) The production has confidence. It even has brio. But it insists on a Hamlet-next-door, and instead he felt as though he were stadiums away.

Helen Shaw writes about theater and performance in publications such as Time Out New York, The Village Voice, TheatreForum, and diversalarums.com.