Helen Shaw

Helen Shaw

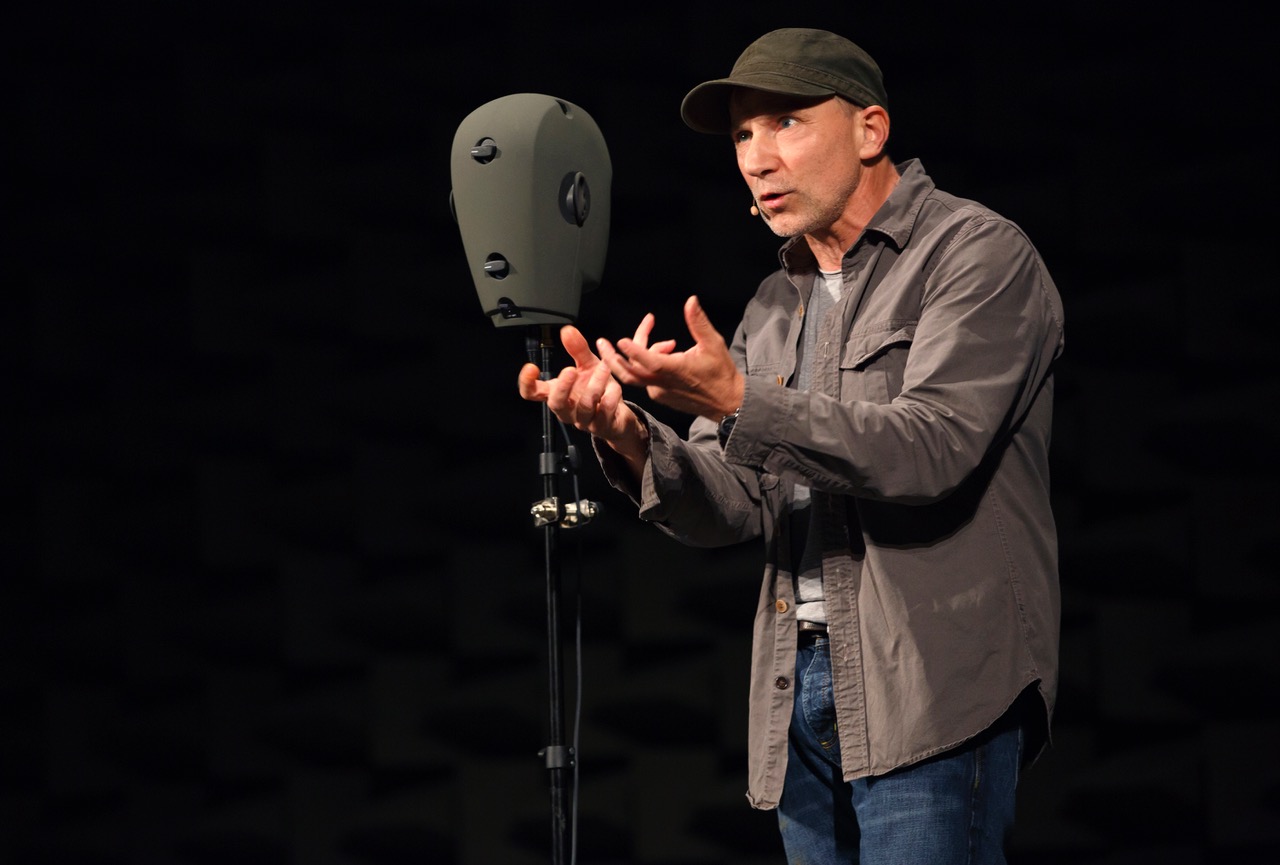

Simon McBurney in The Encounter. Image copyright Joan Marcus 2016.

The Encounter, John Golden Theatre, 252 W. Forty-Fifth Street, New York City, conceived and performed by Simon McBurney

• • •

Communication itself is the slippery subject of Simon McBurney’s hypnotic The Encounter, one of the more unlikely Broadway productions to make it here from across the Atlantic. To the land of the razzle-dazzle kick line, The Encounter brings an exercise in pure storytelling: an hour and fifty minutes of nonstop talk from one man alone onstage. It’s beautiful, even virtuosic. It’s also, for a piece set in the tropics, strangely chilly.

McBurney’s text has been adapted from Petru Popescu’s 1991 book Amazon Beaming, the astonishing tale of photographer Loren McIntyre and his journeys into Amazonia. In 1969, attempting contact with the remote tribe the Mayoruna, McIntyre followed them into the forest and got lost. His intended subjects—“cat people” who claim to be descended from jaguars—were fleeing headlong from an unnamed threat; suddenly, McIntyre was fleeing along with them. Exhausted, hungry, dazed by rainforest hallucinogenics, McIntyre stayed quasi-captive with the Mayoruna for months. He didn’t speak Matsés, and they knew no English or Portuguese. Then, in his loneliness, he began hearing a voice in his mind—what he believed was a Mayoruna chief reaching out to him telepathically.

McBurney and his British company Complicite, known for physical-theater spectaculars like A Disappearing Number and Shun-kin, at first seem to have sent us a piece still in rehearsal. The preshow includes some last-minute repairs to the floor, and McBurney—casual in an army-green shirt and cap—“accidentally” breaks a videotape. But as always in a Complicite piece, the roughness is the surface; underneath, The Encounter is gemlike and gleaming. Complicite’s transitions between scenes have always been micro-miracles: choreographed movement, cinematic fades, video and sound elements making an art of swift changes. In this sense, The Encounter is the company’s technical apotheosis.

Every seat in the Golden Theatre has a pair of stereo headphones attached—we wear them for the duration—and these are gateways to a hugely convincing audio-landscape. (The extraordinary sound environment was created by Gareth Fry and Pete Malkin.) On a stage cluttered with a table and variously strewn water bottles, a gray “binaural head” stands like a totem: Cycladic sculpture by way of Universal Robots. The head’s microphones allow McBurney to broadcast in sonic 3-D. He whispers to the head; he seems to be at our own right shoulder. He blows in the head’s ear; our own gets hot. McBurney plays little tricks, demonstrating his Foley methods, intercutting between prerecorded and live sound. Our own inner monologues are drowned out; the show seems to be coming from inside our own brains. When I slipped off my headset during the performance, hungry for unprocessed sound, I was struck by the rapt silence in the theater. The customary rustlings were absent. All our busy minds were hushed.

Complicite tends to wrap its works in layering onionskins of memory and narration: their pieces often begin with a modern speaker/lecturer who then tumbles us, Inception-style, back through time. The Encounter uses the same method, but here the fusions of now-then, I-him are themselves the actual subject matter. McBurney begins with himself, the outermost concentric ring of storyteller. “I’m taking a picture for my daughter,” he tells us, as he holds up a cellphone. McBurney’s actual daughter will reappear periodically as a voice, interrupting her patient Dadda at his desk where he’s crafting the show. “How long is that head going to be in our house?” she asks about the binaural mannequin, demanding one last snack as McBurney nudges her back to bed. Other voices pipe up, recordings of interviews with scholars, indigenous peoples’ advocates, Popescu himself. In the book, Popescu’s prose moves like a torrent, the perspective shifting between third and first person just as McIntyre’s own sense of reality shifts. In performance, McBurney’s insinuating murmur in our ears and the dizzying swarm of recorded voices also try to knock down our own internal barriers, to send us on an audio-only version of an ayahuasca trip.

Simon McBurney in The Encounter. Image copyright Joan Marcus 2016.

As McIntyre, McBurney phase-shifts his voice down an octave and uses an American accent. “Some of us are friends,” he growls, as the chief’s words appear in McIntyre’s mind. It’s here, in this other-space of communication, that McIntyre learns the Mayoruna’s flight upriver is part of a deliberate unburdening, a way of sloughing off permanence so they can move, collectively, backward in time. Driven to desperate measures by incursions by loggers, the Mayoruna believe that only “at the beginning” can they be safe from invasion by the white man. At the crescendo of this process, the tribe members fling their hunting gear and calabashes into the fire, a destructive ritual that becomes McIntyre/McBurney’s sympathetic climax. Could our own materialistic society ever free itself this way? Do possessions really pin us to time like butterflies to a specimen board? Paul Anderson’s lights go mad as our narrator explodes with ecstatic movement. But while The Encounter certainly disorients us, the show—compressed through those headphones—is too controlled an experience to be genuinely liberating.

Headphones, after all, seal us up; they shift the world we see to a safe remove. In the theater, that remove is dangerous. A certain sadomasochism is bred deep into the theatrical transaction: we like to watch characters suffer in live performances because it lets us be with them, suffering too. In The Encounter, though, the heavily mediated sound signals us that there’s no mess possible here, so the production feels less “live” than it actually is. Our headphone jacks turn us from a collective audience back into individual listeners. Try as I might, I felt myself drifting away from the work even as I admired its dense lyricism. McBurney is a superb performer. He has wild hair and furtive, rather shy eyes—but there’s danger in him; he can shift his weight like a panther. Listening to him on headphones stole away some of that electricity. I had so been looking forward to being in the room with him—and yet ten rows away, he felt unreachably far off.

There is trouble too in those nesting stories. These layers become cocoons, which muffle, and ultimately misplace, the piece’s urgency. On the outside is McBurney and his sweet daughter; beneath is Popescu’s biography; then McIntyre’s struggle (and its foregone happy conclusion); and only then, bundled up like an eggshell in wool, do we find the embattled Mayoruna. This is because each of the three encounter-ers wants to use the few things he knows about the Mayoruna’s time-sense to hotwire his own enlightenment. You can understand McIntyre’s attitude in 1969, but it feels late in the day for such self-centeredness now. “If we decide never to contact tribes anymore,” we hear Popescu say in an interview, “then we will never find out the deepest, most interesting and controversial things about ourselves.” Wait. About ourselves? All three men are respectful, kind, keenly aware of the repercussions of contact. Yet there they go up the Javari river, looking for self-help.

Helen Shaw writes about theater and performance in publications such as Time Out New York, The Village Voice, TheatreForum, and diversalarums.com.