Mark Sinker

Mark Sinker

A lifelong engagement with science and her rural surroundings provides context and complexity to the writer’s miniature worlds.

Beatrix Potter, drawing of a rabbit (Peter Piper), circa 1892–1901. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature, curated by Annemarie Bilclough and Helen Antrobus, Victoria and Albert Museum South Kensington, Cromwell Road, London, through January 8, 2023

• • •

Animal tales have been with us since the cave painting, of course. And two thousand years after Aesop used fables to warn the ancients against types of foolish behavior, the Victorians were still following philosopher John Locke’s seventeenth-century advice that the Greek storyteller was ideal for children learning to read. So it’s no surprise that the twenty-three little books that made Beatrix Potter’s fortune finger-wag now and then: small bunnies to do as mum tells them, empty-headed ducks to beware the gorgeous foxy stranger, squirrels not to act the brash pint-sized prick on an owl’s doorstep . . .

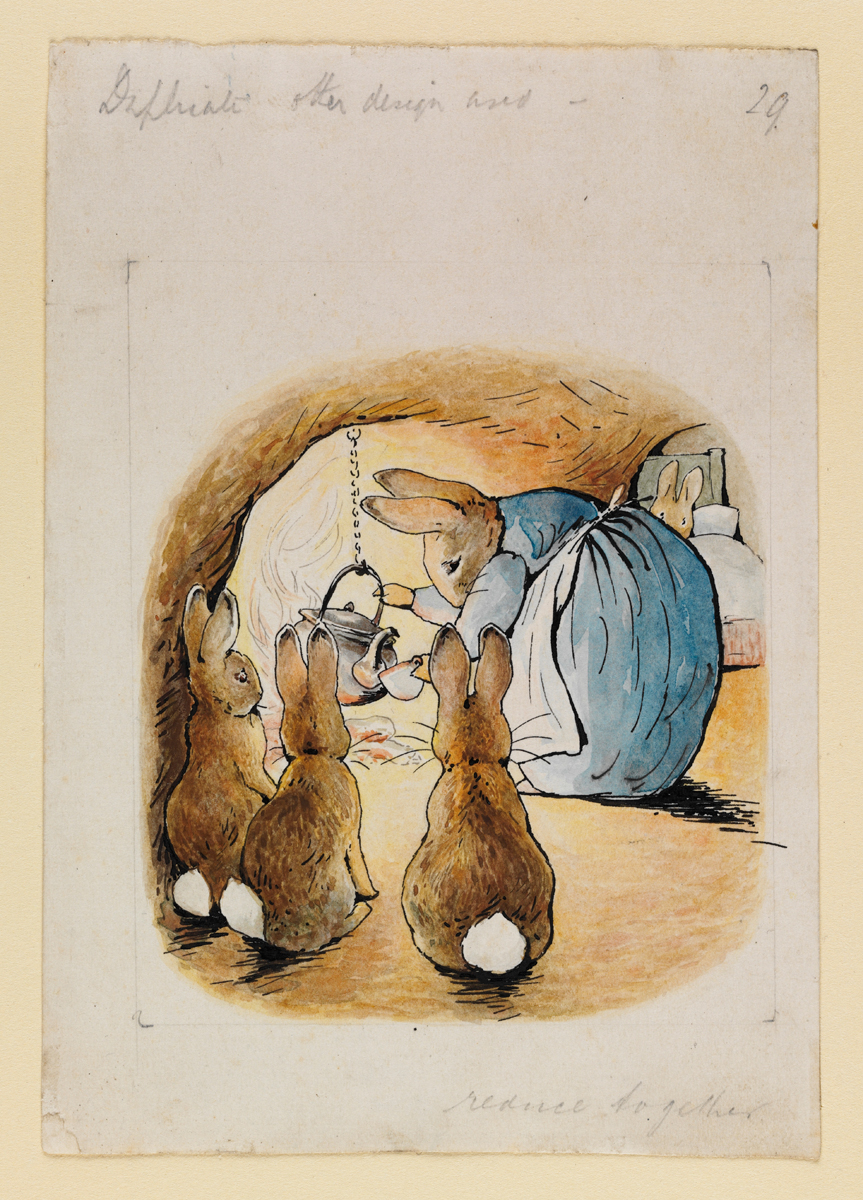

Beatrix Potter, Mrs. Rabbit pouring tea for Peter in The Tale of Peter Rabbit, 1902. Courtesy Frederick Warne & Co Ltd. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Yet there was much more to her work than simple instruction, as demonstrated at the Victoria and Albert Museum by Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature (which, in addition to books, collects more than two hundred personal objects, images, artworks, and letters). Via copies of early editions and spin-off merchandise, we see how her writing career took off between 1902’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit and 1930’s The Tale of Little Pig Robinson, enabling her in her late forties to buy Hill Top Farm and reinvent herself as a Lakeland sheep-breeder, landowner, and conservationist. We also see the many studies from her long apprenticeship as an artist and the landscapes she sketched on family holidays for her own relaxation and pleasure.

Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature, installation view. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

As always, the V&A surrounds the art with items from the life: sepia family photos, pages from her journal, quilts and textiles evoke the feel and context of a comfortable Victorian childhood. Her parents were enthusiastic amateur artists, her father a barrister at large in liberal London who loved to draw a flying duck in a bonnet. With few friends her own age, perhaps by overprotective parental decree or perhaps by temperament, and homeschooled by governesses, Potter grew up in eager walking distance of the grand Kensington museums. With her adored brother Bertram, she ran her own personal natural history department at the top of the house: alongside studies of various museum items, we find sketches of her many beloved pets—rabbits, mice, snails, salamanders, an owl, a frog, a hedgehog—and sometimes of their bones.

Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature, installation view. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

In 1940, toward the end of her life, Potter summarized the dynamic of her fiction for the editor of the Horn Book, a magazine dedicated to excellence in children’s literature. She could never, she wrote, “remember a time when I did not try to invent pictures and make for myself a fairyland amongst the wild flowers, the animals, fungi, mosses, woods and streams, all the thousand objects of the countryside.” The word fairyland is worth marking. The painter John Millais, a friend of the Potter family, had praised young Beatrix for her powers of observation—and the Pre-Raphaelites often embedded their legendary or religious subject matter within British plant life precisely studied and realized, as did the Victorian Fairy Painters (Richards Doyle and Dadd and others), with their tiny courts and legions wooing and spikily warring. Potter’s miniature idylls are surely less myth-laden, but this was a device of hers also.

Beatrix Potter, The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle artwork, November 1904–July 1905. Watercolor and ink on paper. © National Trust Images.

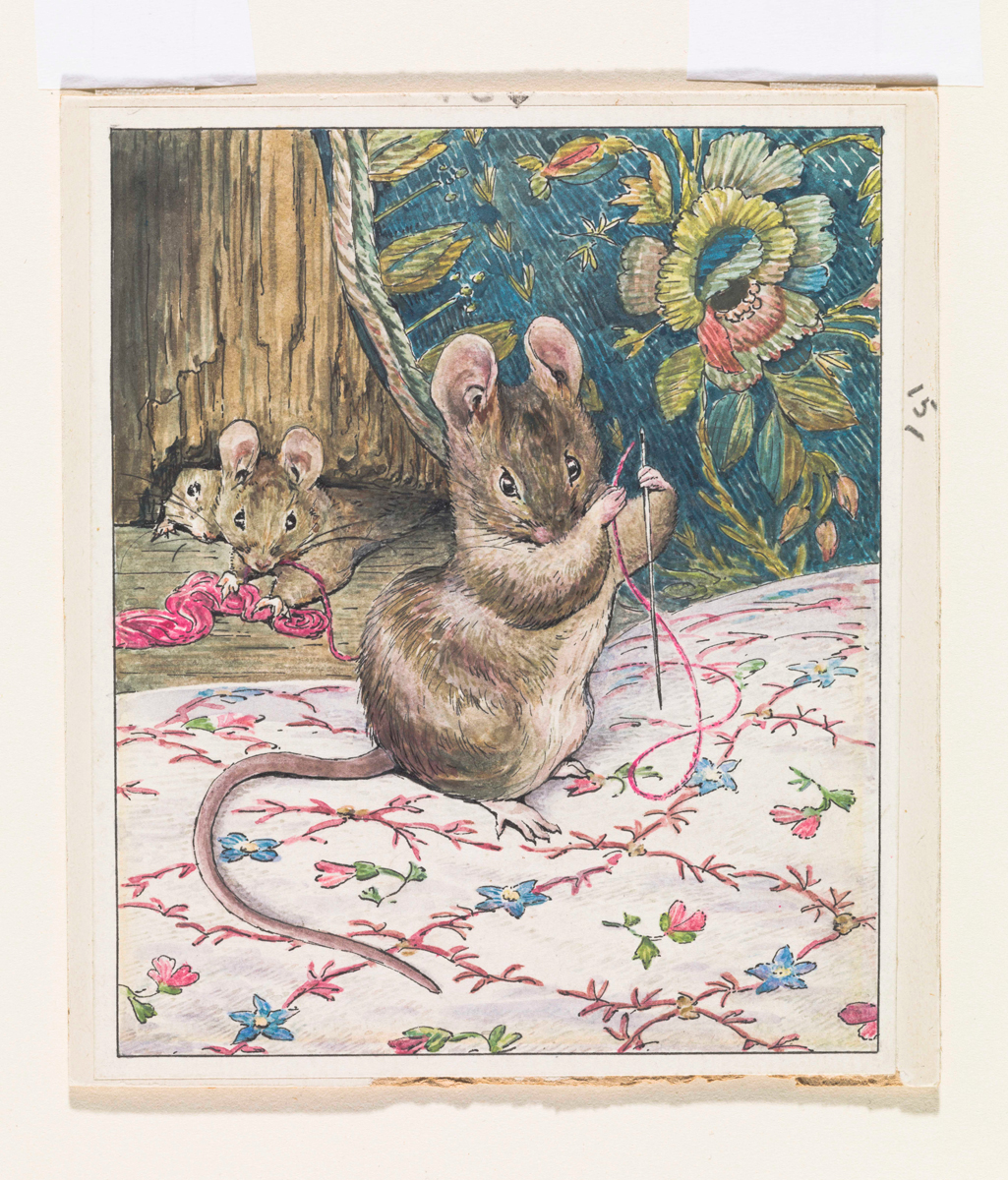

Indeed, The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle (1905) is straightforwardly an encounter with the Wee Folk: the busy washerwoman that a small child meets is not as she seems, her grinning muzzle perhaps less elfin than unnervingly toothy. Based on rumors fashioned around or by a contemporary of Potter’s, a Mr. Prichard, The Tailor of Gloucester (1903) is also a version of Grimm’s “The Elves and the Shoemaker.” As helpful elves the mice also model the intricate costumes of an earlier century, while the cat Simpkin is center stage, bilked of his rightful supper (the mice) and superbly disgruntled about it. (The tailor is almost a minor character, being largely bedridden.) Key to the narrative are the detailed pains taken by mice and man with the embroidery Potter had once so closely studied at the South Kensington Museum (today the V&A)—but as with Tiggy-Winkle, the nature of the exhibition title defers to the brute strangeness of the animal world, and to observed personality wild or domestic.

Beatrix Potter, “The Mice at Work: Threading the Needle,” The Tailor of Gloucester artwork, 1902. Watercolor, ink, and gouache on paper. © Tate.

For a time Potter’s goal had been to master Victorian scientific illustration as a profession—as impressively represented here, fungi and mycology in particular fascinated her, and the experts she corresponded with acknowledged her gift for this subject at once technically tricky and unladylike. Too much is sometimes read into this—I’ve seen a journalist claiming Potter could even have been a second Darwin, if only the men who decide had allowed it. But becoming the first and only Beatrix Potter was hardly just a consolation prize. A rich strand in the show is her meticulous planning, shaping, editing, and proofing of the books: on view are roughs and preparatory drawings, and a covetable concertina-form mock-up of the whole of The Story of a Fierce Bad Rabbit (1906). Without all this, her loving re-creations of Lakeland views and gardens would have no rooms devoted just to them—because they derive their meaning as backdrops in known tales: be it Fawe Park as McGregor’s kitchen garden, or Derwentwater for the rafts of the squirrels, or Hill Top’s paths and stiles, as seen in several of the titles.

Beatrix Potter, garden at Gwaynynog Hall, Denbighshire (later home of the Flopsy Bunnies), probably March 1909. Watercolor and pencil on paper. Courtesy Frederick Warne & Co Ltd. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Potter’s successors (such as Alison Uttley of the Little Grey Rabbit books) often sentimentalized the norms of English village ruralism as the society a reader identified with. Potter’s wry loner’s eye is more restless, and here nature tends toward a subtly mischievous comedy of manners. Tom Kitten’s many scrapes, for example, reflect poorly on his mother Tabitha Twitchit’s wisdom, and she usually features in the tales as a bit of a snob and a scold, while Tom’s foray up her open stove-chimney lands him in a twilight criminal lair resembling Mayhew’s London, where the corpulent rat Samuel Whiskers and wife (1908) busily encase him in a roly-poly pudding in a famously funny and dreadful image.

Beatrix Potter, The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck artwork, 1908. Watercolor and ink on paper. © National Trust Images.

As for poor Jemima Puddle-Duck (1908), her desire to hatch her own eggs ends badly, as the hounds who chase off her whiskered gentleman captor gobble them up, and she is returned to the carceral servitude of the eighteenth-century farm. This charming world gets dark very quickly.

Beatrix Potter, page from a sketchbook, circa 1875. Watercolor over pencil on paper. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

In a cave painting, the realism is a shamanic conjuring of desired outcome or identification. For Aesop, an ant or a lion or a crow is the ironized figure for a psychological type. But the context the show gives Potter’s tales sees her stubbornly empirical perception—the heart of the science of the day—ungluing as often as it binds, as anthropomorphic satire merges with the quietly lethal basis of rural life: Little Pig Robinson’s aunts, in the author’s words, “led prosperous and uneventful lives, and their end was bacon.” Thus the blunt truth beneath the ideal.

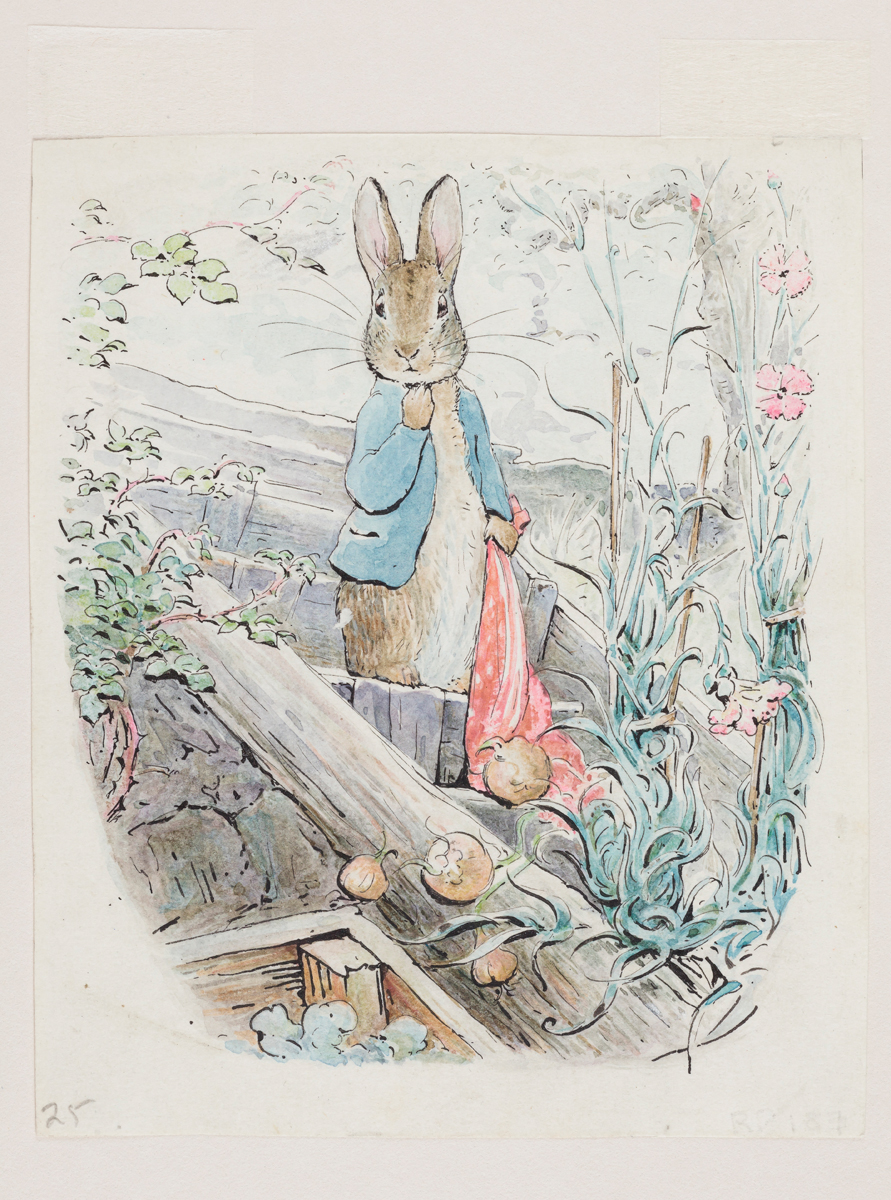

Beatrix Potter, Peter with handkerchief in The Tale of Benjamin Bunny, 1904. Watercolor and pencil on paper. © National Trust Images.

Turn back now to Peter Rabbit (1902), whose story we first see sketched in vivid pen line in her letters to the children of a former governess, cartoons with a throwaway liveliness that anticipates and sometimes betters the images we know so well. In the book these figures become bold and reader-friendly, the color-field to the little blue coat is memorable, even iconic—and yet Peter is not a simple and still less a twee figure. Gaze at him as he gazes back at you, or else as he enigmatically nibbles a radish. What’s on his mind? The character was developed from a well-loved pet, the expression taken from life—but how do we even begin to parse it?

Mark Sinker has written about music, film, and the arts since the 1980s, at outlets including Sight and Sound, Crafts magazine, the Face, and the Village Voice. In the early 1990s he was editor of the Wire, and in 2019 published an anthology of essays and conversations about UK music writing, A Hidden Landscape Once a Week: The Unruly Curiosity of the UK Music Press in the 1960s–80s, in the words of those who were there.