Rahel Aima

Rahel Aima

In Alien Property and Exquisite Corpse, an exploration of empire, bombs, and family history.

Rayyane Tabet, Dear Victoria, 2016–ongoing, from Fragments, 2016–ongoing. Reading, 25 minutes. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

Rayyane Tabet: Exquisite Corpse, curated by Ryan Inouye, Sharjah Art Foundation, Al Mureijah Square, Sharjah, UAE, through June 15, 2021; the project is also accessible via the artist’s online archive

• • •

In 1943, a British phosphorus bomb hit the Tell Halaf Museum in Berlin. Everything burned down. Even the collection of statues and friezes made from basalt (a material born of flames) exploded into smithereens. Built in 1930, the museum had housed the findings of German diplomat Max von Oppenheim, who in 1899 had discovered, in that way Europeans do, the remains of a neo-Hittite settlement in Ottoman Syria that dates back to the sixth millennium BCE. (Locals told him where to dig: they believed the figures to be cursed and wished them gone.) The same year that the museum was bombed, the United States invoked the Alien Property Custodian Act to seize eight orthostat friezes that Oppenheim—an enemy national—had left in storage; the Met bought all of them, ultimately keeping four for its collection.

Following his first excavation of the site in 1911–13, Oppenheim returned in the 1920s, after European agreements had carved up the region and awarded jurisdiction of Syria to the French. The latter suspected Oppenheim of being a German intelligence officer mapping the land and radicalizing local tribes, like so many dilettante archaeologists and ethnographers of the time. They appointed a Lebanese translator, Faek Borkhoche, to act as Oppenheim’s secretary and report on his movements: to spy on the spy. Borkhoche’s field notes were discovered, in that way artists do, by his great-grandson Rayyane Tabet, who unspools his own mining of archaeological and personal histories in the ongoing project Fragments (2016–).

In Alien Property, which opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2019 and is still on view, Tabet installed his works alongside the museum’s Tell Halaf friezes and a loaned monumental sitting figure to magnificent effect. A vitrine holding Borkhoche’s personal correspondence, photos, and a gifted copy of the book that Oppenheim wrote about Tell Helaf is complemented with two audio pieces narrated by Tabet that are available online; institutional documents related to the Met’s purchase of the orthostats are displayed in another case. On the walls are charcoal rubbings of thirty-two orthostats owned by various European and American museums, arranged as they would have been on the Tell Halaf palace wall, and a family tree illustrated by a Bedouin goat-hair rug that Borkhoche willed to be cut up and divided by each subsequent generation until it disappeared. Currently, it is in twenty-three sections. Objects separated by history are reunited and made whole, not unlike the statue, reconstructed from the Berlin museum’s rubble.

Rayyane Tabet, Basalt Shards, 2017 (installation view). From Fragments, 2016–ongoing. 1,000 charcoal rubbings on paper, wooden palette; dimensions variable. Photo: Shanavas Jamaluddin.

Exquisite Corpse at the Sharjah Art Foundation is a quieter affair. It illuminates an unfortunate truth: cultural patrimony that is exported to the West as an undamaged whole returns to the region as fragments, to be subsequently reinterpreted and marketed as artwork. Here, such patrimony is reconstructed into Franken-narratives and assemblages otherwise known as archives. When Allied forces bombed the Tell Halaf museum, the basalt works shattered into approximately 27,000 shards, 26,000 of which have been reassembled. A thousand pieces couldn’t be matched to any specific object, although their broad provenance is unquestioned; they remain in storage. It’s hard not to see them as an extended metaphor for the various peoples—Bedouins and Palestinians especially—displaced by the cluster bomb of agreements that divided up the Levant.

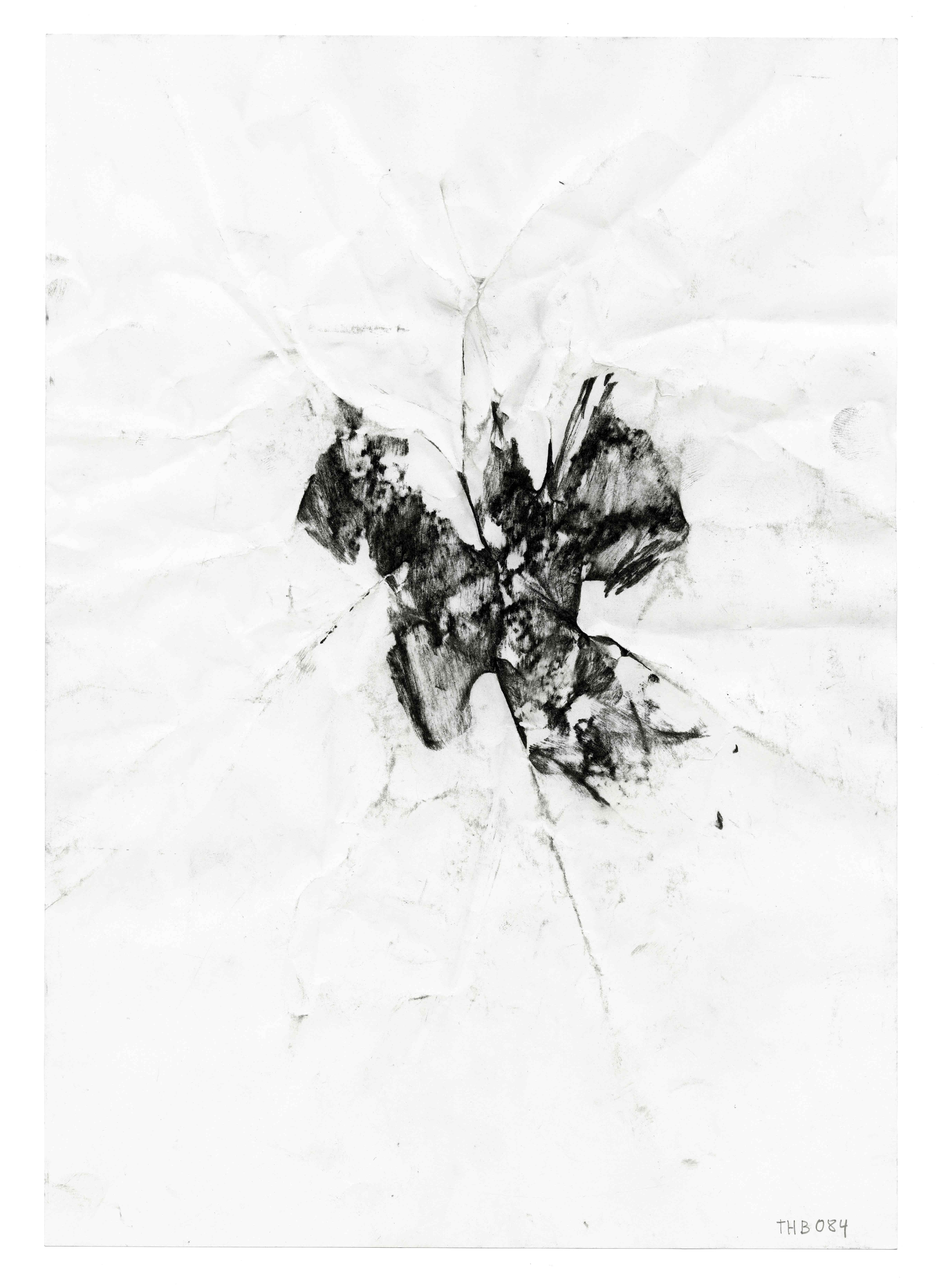

Rayyane Tabet, Basalt Shards, 2017 (detail). From Fragments, 2016–ongoing. 1,000 charcoal rubbings on paper, wooden pallets; dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery.

Tabet’s New York show features rubbings that function as detail shots, isolating single bodies from the bigger orthostat. A leaping lion, a rearing horse, an armored warrior. In Sharjah, the artist instead makes one thousand rubbings from the one thousand mystery fragments. In Basalt Shards (2017), three walls of a cavernous gallery space are lined with wooden shipping pallets that are then crowded with the rubbings. Perhaps we could see it as a gesture that accords these discards the same dignity as the unbroken reliefs. But it becomes more interesting to engage in a kind of speculative pareidolia, hunting for meaning in the abstraction. “This one is like a crocodile,” my mother remarks gleefully, looking interested for the first time: without the considerable context provided by Tabet’s audio works in NYC, and no wall text here, she’s given no entry point into the show. She finds another rubbing that does, I must agree, very much resemble an ocelot or similar wild cat.

Rayyane Tabet, Portrait of Faek Borkhoche, 2021 (installation view). Suitcase, snakeskin, book, documents; dimensions variable. Photo: Shanavas Jamaluddin.

In the next room, Tabet’s great-grandfather is reanimated (somewhat) through Portrait of Faek Borkhoche (2021), a sterile museological display that includes photographs, personal correspondence, a snakeskin, a boxy suitcase, and 230 Xeroxed pages of his field notes. They are all displayed under glass on angled shelves that run continuously around the walls of the room, occasionally interrupted by cases on pedestals. Written in cursive French and Arabic, they detail the Tell Halaf dig—there might be a little sketch of an interesting ceramic, for example—and also record Borkhoche’s interviews with Bedouin tribespeople, in which he learns about the topology and cultures of the area. A printed circular from Damascus, featuring a list of information to glean from each tribe (name, leader, summer and winter haunts, number of houses or tents, war cry, and so on), suggests a level of standardization, and the presence of many Borkhoches, each trailing their own ethnographer.

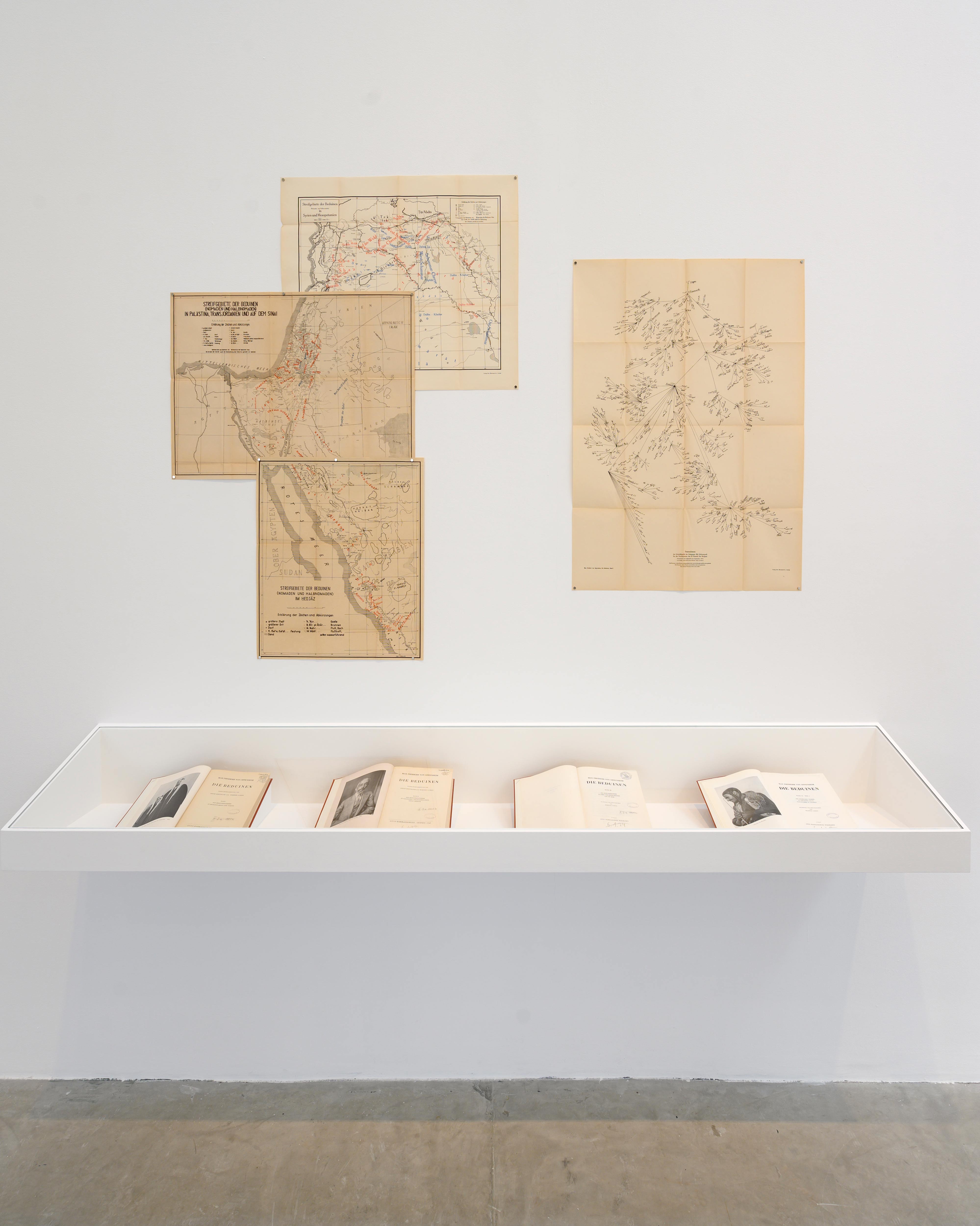

Rayyane Tabet, Exquisite Corpse, 2017 (installation view). Military tents, maps, genealogical tree, books, stakes, rope; dimensions variable. Photo: Shanavas Jamaluddin.

If Portrait of Faek Borkhoche reveals a casual imbrication of archaeology, anthropology, and empire, those links become most overt in the show’s titular installation, Exquisite Corpse (2017). Here, various US and European military tents, all in close shades of olive or camo green, are hung from the ceiling and bisect the gallery like a segmented caterpillar. Colonial maps, ropes, stakes, and miscellaneous hardware are organized by type and hung on the walls. A display case holds Oppenheim’s well-received tome on Bedouins, which is to say, a synthesis of Borkhoche’s research.

Rayyane Tabet, Exquisite Corpse, 2017 (detail). Military tents, maps, genealogical tree, books, stakes, rope; dimensions variable. Photo: Shanavas Jamaluddin.

Each of the three halls in Sharjah follows a similar format, with an installation usually placed in the middle and documentation lining the surrounding walls, which produces an effect of exhibition-as-footnoted text. Without Tabet’s spoken narrative or the powerful presence of the Tell Halaf artifacts themselves, the show begins to feel like an ethnographic mise en abyme. Its museological austerity begins to grate. We come to understand Tabet to be reprising a similar anthropological role with his charcoaled documentations of unclassifiable shards and methodical lineup of various camping accoutrements.

Rayyane Tabet, Ah, my beautiful Venus!, 2017 (installation view). 6.5 tons of basalt, wooden trestles, foil pressings, shipping documents; 200 × 1300 × 500 cm. Photo: Shanavas Jamaluddin.

Remember that sitting figure in New York? It was Oppenheim’s favorite of his finds; he is said to have called it “my beautiful Venus,” and his grave features a replica of the base of the figure. In another large-scale installation in Sharjah, Tabet abstracts the statue, recasting it as six-and-a-half tons of basalt that was quarried elsewhere in Syria and cut into square tiles. The tiles are unevenly stacked to create little platforms with wooden plinths, which are topped with foil pressings from Oppenheim’s original plaster mold of the Venus, cast when he first encountered it in 1911. Like the rubbings, they isolate single features: a face, two ears. Shipping records displayed on the walls detail the installation’s movement, not as wood or basalt but as an artwork to be bought and sold. Along the way, cultural heritage is transformed into aesthetic value.

Rahel Aima is a writer from Dubai. She is editor of BXD: The Postwestern Review, an associate editor at Momus, and was the co-editor of THE STATE. She is currently at work on a book about where oil meets water in the Arabian Gulf.