Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

An essay to accompany a film series at Metrograph.

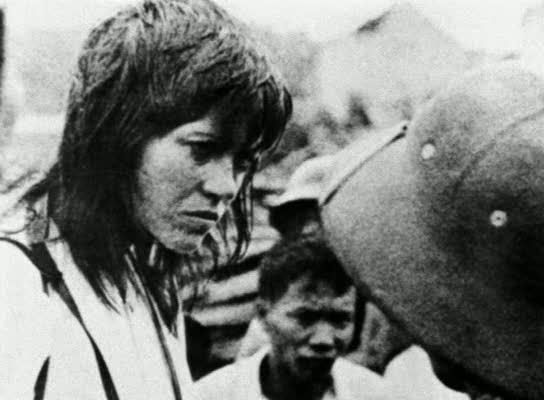

Jane Fonda as Suzanne in Tout va bien. Image courtesy Janus Films.

What is a star, and how does one function? Richard Dyer, the British cinema scholar who established star studies nearly forty years ago, helped pin down the slippery concept with this maxim, found in his 1986 book, Heavenly Bodies: “Stars matter because they act out aspects of life that matter to us; and performers get to be stars when what they act out matters to enough people.”

The expression “act out” takes on a double meaning when considering the career of Jane Fonda in the 1970s. In that decade, the performer, born in 1937, established herself as “the most politically outspoken star in Hollywood history,” as the critic J. Hoberman wrote in a 2001 reappraisal of Fonda. Onscreen in the ’70s, she acted out the parts for which she would win her two Best Actress Oscars: the haute-boho sex worker Bree Daniels in Alan J. Pakula’s neo-noir Klute (1971) and the initially meek military wife Sally Hyde in Hal Ashby’s 1968-set drama Coming Home (1978). Off-screen during this decade, her political activism, particularly her steadfast opposition to the Vietnam War, led her detractors to accuse her of another kind of acting out: misbehaving. The Fonda of this era remains the paradigm of how—if, in fact, it’s even possible—to reconcile the committed citizen with the celebrity.

Fonda’s attackers in the ’70s included Richard Nixon, who placed her on his “enemies list.” More insidiously, they also included Jean-Luc Godard, who banked on the actress’s engagé persona only to exploit it in a project he codirected with Jean-Pierre Gorin: Tout va bien (1972), an ideologically dense film about the fracturing of post-’68 France that’s anchored by a squabbling couple played by Fonda and Yves Montand. Far-leftist confrères, Godard and Gorin also collaborated on Tout va bien’s acid addendum, Letter to Jane. In this fifty-two-minute essay film, both men volubly analyze a photo—showing a stern-faced Fonda meeting with North Vietnamese citizens in Hanoi—that ran in a 1972 issue of the French newsweekly L’Express. Near the end of their semiotic scrutiny, Gorin delivers this icy indictment: “One must realize that stars are not allowed to think.”

What is a star, and what is one permitted to do? A decade before Letter to Jane, Fonda was the subject of another, more sympathetic nonfiction film: Jane (1962), overseen by the American direct-cinema innovator Robert Drew. The nearly hour-long portrait follows the actress, then only two years into her career and not yet twenty-five, in the weeks leading up to a top-billed theater performance. “Jane Fonda, daughter of a famous actor, preparing for her first opening night as a star on the Broadway stage,” the narrator announces at the beginning of Jane, as we see her at a fitting. The appositive in this intro underscores how much being the child of Henry Fonda burdened the actress in the first decade of her profession, when she was defined not by her politics but by her patrilineage. Fonda fille articulates that anxiety in Jane when she notes the resentment she’s felt from colleagues, who are certain that any part she’s landed up to that point resulted not from her talent and dedication but from the sheer dumb luck of the family she was born into. Even in the nascence of her stardom, she was regarded warily—skepticism that her actor brother, Peter, two years her junior, largely escaped.

Jane Fonda as herself Sois belle et tais-toi. Image courtesy Center Audio-Visual Simone de Beauvoir.

She was also regarded—as most actresses have been since the birth, nearly a century ago, of the cinema star system—as raw, imperfect material to be reshaped. Fonda lucidly reflects back on the indignities she faced in the first years of her career in Delphine Seyrig’s little-seen documentary Sois belle et tais-toi (Be Pretty and Shut Up, 1981), a survey shot in the mid-’70s of twenty-three American and European actresses, who share their experiences of the film industry’s entrenched sexism. Clearly at ease with Seyrig—a fellow actress-activist of the era, and Fonda’s castmate in Joseph Losey’s 1973 adaptation of Ibsen’s proto-feminist stage landmark A Doll’s House—she recalls her humiliating, but far from atypical, makeup test for Warner Brothers. That studio released Fonda’s first film, Joshua Logan’s Tall Story (1960), a college-campus romp in which she plays a husband-hunting cheerleader. “It was like I was coming off an assembly line,” Fonda says, discussing the maquillage experts who insisted that she dye her hair blond and encouraged her to have her jaw broken, to give her more sunken cheeks. (She agreed to the former but said no to the latter.) Logan, who was also Fonda’s godfather, suggested she’d need even further facial alteration. She recalls his assessment: “ ‘You’ll never play in a tragedy because a nose like that cannot be taken seriously.’ ” Her nose remained intact; her conception of herself did not. “I, Jane Fonda, was here and this image was there, and there was this alienation between the two,” she tells Seyrig.

What is a star, and what is one allowed to say—and how? Fonda relays those anecdotes to Seyrig in French, which is the same language she speaks in Tout va bien and in two films she made with Roger Vadim, the first of her three husbands: La Ronde (1964) and La Curée (1966, a.k.a The Game Is Over). In this pair of movies, as with nearly all of her work from the ’60s, in any tongue, Fonda performs some variation on the soubrette or the sex kitten—types that could fall under the category “ridiculous woman,” as the actress bluntly describes her Tall Story character to Seyrig. The most outlandish of these ridiculous women—and the last one she would play, not just in the ’60s but ever again—was the title character in Barbarella (1968), her final film with Vadim.

Fonda ended that decade with the movie that proved her dexterity in a serious part: Sydney Pollack’s Depression-set They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969), in which she stars as one of several scores of contestants in a grueling dance marathon vying for a $1,500 prize. By 1970, she was filming Klute and had embarked on her most politically radical period, which would last for the next four years (and for which she would become a target of COINTELPRO, the FBI’s covert, frequently illegal program of surveilling and discrediting “subversives”). “What I did was talk—all the time, everywhere, on and on and on in a frantic voice tinged with the Ivy League,” Fonda writes in her autobiography, My Life So Far (2005), of this epoch, one marked by not only her antiwar activism but also her commitment to the Black Panthers, feminism, economic justice, and American Indian rights.

Yes, she talked, but she also knew the power of reticence. Seconds before her name was announced at the Academy Awards ceremony on April 10, 1972, as the Best Actress winner for Klute, Fonda whispers something to Donald Sutherland, her date that night and her costar in the film. Sutherland had also helped her organize the FTA show—as in “Fuck the Army”—an antiwar revue that he, Fonda, and others performed in ’71 for US servicemen and women, both at home and in the Pacific Rim. (Francine Parker captured the overseas leg of the tour in her 1972 documentary, F.T.A., which features many soldiers speaking on camera about their disgust with the military. The growing antiwar sentiment inside all branches of the US Armed Forces led to the GI movement, with which Fonda’s activism was most closely aligned.)

Jane Fonda as herself in F.T.A. Image courtesy American International Pictures.

Were the attendees of the Oscar gala, who clap politely, almost tepidly, as Fonda walks up to collect her gold statue, bracing themselves for a harangue? Onstage, she bows and smiles. She thanks the members of the Academy and those who applauded. Then, after a dramatic pause, a slight exhale of breath, and another smile, she concludes: “There’s a great deal to say and I’m not going to say it tonight. I would just like to really thank you very much.” She quickly exits.

Fonda’s ’72 acceptance speech is one of the shortest and most potent ever delivered at the Academy Awards, an event that has often served as a showcase for overweening sanctimony and toothless political peroration. In a pleasing irony, Fonda’s taciturn remarks were made at a ceremony lauding her portrayal of a character who, among other things, is undergoing the talking cure. Three crucial, spellbinding segments in Klute feature Bree Daniels in her matronly analyst’s office, sorting through her irreconcilable feelings: about sex work, about the profession she aspires to (acting), about the man she’s growing emotionally attached to (Sutherland’s eponymous private detective, who’s protecting Bree from a sociopathic killer).

Jane Fonda as Bree Daniels in Klute. Image courtesy Warner Brothers.

At Fonda’s request, these episodes in Klute were shot last and were entirely improvised. Her therapist is played by Vivian Nathan, one of the original members of the Actors Studio. (With its emphasis on Method acting, the organization had revolutionized performing in the US by the mid-twentieth century; Fonda studied there early in her career. “It was nothing like what I’d known at the Actors Studio,” Fonda says in Sois belle of her Tall Story role.) Fonda is electric in every moment of Klute, but watching her in these scenes with Nathan is like witnessing the sparks of a Tesla coil. Operating on alternating currents, Bree is a dynamic study in contradictions—an imperfect yet indelible symbol of second-wave feminism, the cresting of which nearly coincides with Klute’s release. According to Patricia Bosworth’s Jane Fonda: The Private Life of a Public Woman (2011), Fonda credited her off-screen activities for improving her performances: “On breaks Jane would tell Nathan she was sure her politics were nurturing her acting. Politics had made her more aware, more open.”

What is a star, and how does one change? A month after Fonda won her Academy Award for Klute, she received an invitation from a North Vietnamese delegation to visit Hanoi and the surrounding area, to witness firsthand the destruction of the country wrought by the US. She arrived in the capital city, alone, on July 8, 1972, and stayed for two weeks. While there, she met with American POWs and recorded broadcasts for the Voice of Vietnam radio, to relay to US pilots the damage she saw on the ground and to implore them to stop bombing (an excerpt: “The people beneath your planes have done us no harm. They want to live in peace. They want to rebuild their country”).

Jane Fonda as herself in Letter to Jane. Image courtesy Janus Films.

It was during this trip that the photo of her so disapprovingly dissected in Letter to Jane was taken—as was the most notorious snapshot of Fonda, the one for which she would be lambasted as “Hanoi Jane,” an epithet still deployed today. The photo, from her last full day in North Vietnam, shows her, with a helmet on and an incongruously gleeful expression on her face (she’s singing a Vietnamese song she had memorized to her soldier hosts), sitting on an antiaircraft gun. Admitting later to horrible misjudgment, Fonda writes of the incident in her memoir, “If I was used, I allowed it to happen. . . . I realize that it is not just a U.S. citizen laughing and clapping on a [North] Vietnamese antiaircraft gun: I am Henry Fonda’s privileged daughter who appears to be thumbing my nose at the country that has provided me these privileges.”

Ever since the publication of that photo—a still image that has threatened to eclipse any moving-image work she has ever done—Fonda has repeatedly apologized for her lapse, careful to separate it from her antiwar activism as a whole, for which she, rightly, has no regrets. Upon her return to the US in late July ’72, the State Department assailed her, and the Veterans of Foreign Wars passed a resolution insisting that she be prosecuted as a traitor. The overwhelming antipathy from the government (and civilians) did not dissuade her from her cause: that September, she embarked on the Indochina Peace Campaign, a cross-country antiwar speaking tour that she organized with Tom Hayden, soon to be her second husband. In 1974, the penultimate year of the war, Fonda made her second visit to North Vietnam, this time with Hayden and their infant son. The trip served as the basis for the documentary Introduction to the Enemy (1974); shot and directed by Haskell Wexler, the film, as Fonda recalls in her book, was “aimed at showing a human side of Vietnam, a view of the people’s lives and stories very few Americans would otherwise ever see or hear.” The chronicle, an affecting work of diplomacy, succeeds in its mission.

Later in the ’70s, Fonda would be the main attraction in another kind of fence-mending vehicle. Introduction to the Enemy was the first release of her production company, IPC Films, which repurposed the initials of the Indochina Peace Campaign and was formed in 1973. That year she also conceived of the project that would eventually morph into Coming Home, a film partially inspired by Ron Kovic, the paralyzed Vietnam vet with whom Fonda had recently shared a platform at an antiwar rally. Kovic’s analogue in Ashby’s 1978 movie, set during the Vietnam War but debuting three years after it, is Jon Voight’s Luke, a paraplegic former marine recovering in a chaotic, understaffed VA hospital.

Jon Voight as Luke Martin and Jane Fonda as Sally Hyde in Coming Home. Image courtesy United Artists.

It is with Luke—emotional, tender, a superior lover—that Fonda’s Sally, the dutiful spouse of a tyrannical marine corps captain, played by Bruce Dern, transforms. While her husband is overseeing more carnage in Southeast Asia, Sally volunteers at the hospital and begins an affair with Luke, with whom she has her first orgasm. She changes her hair. She becomes somewhat politicized, outraged by the treatment the vets are receiving. I don’t mean to diminish Fonda’s acting in Coming Home, which is characteristically sensitive, nuanced, and alert. But the film, an absorbing marital melodrama, for which she won her second Best Actress Academy Award, may be too gentle. The conciliatory tone is reflected in the closing of Fonda’s acceptance speech at the Oscar ceremony on April 9, 1979: she thanks Hayden for helping her “believe that besides being entertaining, movies can inspire and teach and even be healing.”

Who is Jane Fonda, and what have I said about her? As an actress and an activist, Fonda did her most significant, and bravest, work in the 1970s. She has remained dedicated to both pursuits (in the latter category, she’s been particularly devoted to adolescent sexual health). Over the following decades, she has reinvented herself more times than any star of her stature: fitness sage, wife of Ted Turner, temporary retiree (she took a fifteen-year break from films after 1990’s Stanley & Iris), to name just a few of her incarnations. She has been, often by her own admission, a jumble of generative, sometimes confounding contradictions. To summarize further would be foolish. All I can do is paraphrase her legendarily brief remarks on that 1972 Oscar night: there’s—still—a great deal to say.

Melissa Anderson, co-organizer of “Jane Fonda in the ’70s,” is the film editor of 4Columns. From November 2015 until September 2017, she was the senior film critic for the Village Voice. She is a frequent contributor to Artforum and Bookforum.