Ratik Asokan

Ratik Asokan

Desire, anguish, and the sublime in the poetry of cult writer

Forough Farrokhzad.

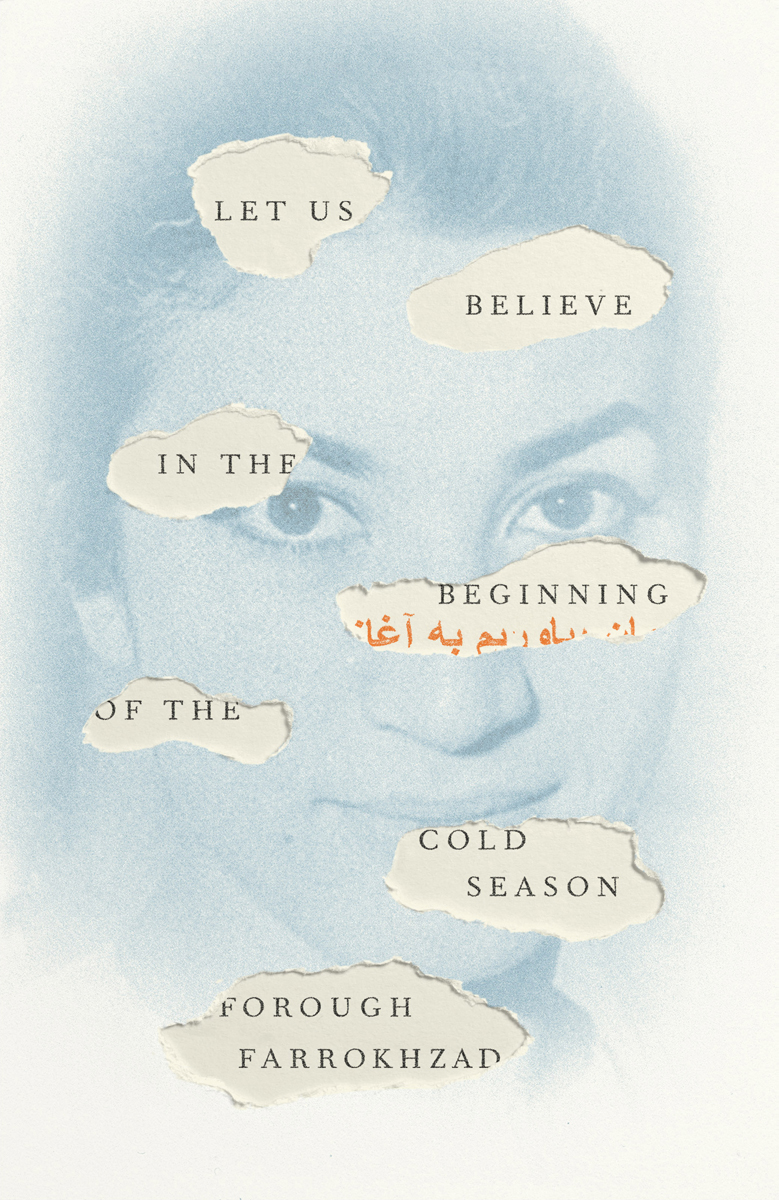

Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season: Selected Poems,

by Forough Farrokhzad, translated by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr.,

New Directions, 107 pages, $16.95

• • •

Forough Farrokhzad was hardly nineteen years old when her first poems appeared in the Iranian journal Rowshanfekr (Enlightened) in 1954. On a four-page spread, they were placed beside a pair of fetching photographs of the poet, who was identified as a mother with a two-year-old son in a biographical note that also praised her “disheveled hair.” Humiliated by one of the poems, “Sin,” which recounted, in the first-person, an extramarital affair, her husband stayed home for a week after the issue hit newsstands. The couple soon divorced, though not before Rowshanfekr’s editor, Nasser Khodayar, published a thinly fictionalized account of his liaison with Farrokhzad.

Such were the pressures that shaped her brief, meteoric career, which was cut bitterly short by a fatal car crash in 1967. In little over a decade, she authored five slim books that address romance and sexual desire, private anguish and political frustrations: taboo subjects “in a society concerned obsessively with keeping the worlds of men and women apart, with an ideal of feminine as silent, immobile, and invisible,” as Farzaneh Milani notes in her study Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Woman Writers (1992). Composed in the prerevolutionary era, when Mohammad Reza Shah was embarking on an ambitious program of liberal reform, Farrokhzad’s poetry comprises, in Milani’s words, “an accurate portrayal of the pain and pleasure of a whole generation undergoing radical change.” Equally praised and condescended to in her time, she is now a cult figure, whose books, censored since the Islamic Republic was established in 1979, remain popular on the black market, and whose life is depicted in biographies and novels.

Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr.’s new translations bring Farrokhzad’s vision into focus for Anglophone readers. Choosing a representative sample of forty poems, Gray has made stark, astringent, and visually striking versions that sit comfortably in their new language, as few earlier attempts have. Farrokhzad has a mystical sensibility, which is a challenge for the translator, who must strike a balance between the poem’s worldly material and spiritual tone. It is a mark of their success that Gray’s renditions pull the reader along as they attain liftoff.

Farrokhzad’s poems, which tend to take the form of a monologue or an apostrophe, combine a frank, at times plangent address with otherworldly yearning and visions of the sublime. Part of the attraction is the ease with which she moves back and forth between these registers, not least when depicting eros: “I seek nothing but the echo of a song / In moans of pleasure that are more pure / than the simple silence of sorrow.” A similar tension flickers on a structural level. Though Farrokhzad’s poems are longish (two or three pages) and usually paint a picture, the setting is sparse, whether indoors or outdoors, with one or two prop-like objects—a window, a cage, a road, the moon—that gradually reveal their metaphorical significance. It is as if the scene is at once forming and dissolving before the reader’s eyes, a dynamic effect that Gray catches:

In the night, something is happening now

The moon is red and agitated

and above this roof that fears it will crumble at any moment

clouds like a crowd of mourners

wait for the moment to rain

More subtly, she follows Farrokhzad when the poet herself experiences a sense of dissolution, either with the beloved (“I abandoned myself in a shadow / in the untrustworthy shadow of love”) or the cosmos (“my whole life . . . / turned across the fleeting moment /and drifted across the face of oblivion”). It is the mixture of intimacy and strangeness, of conviction and uncertainty, that keeps these lines afloat. Either overfamiliarity or distance would have sunk them.

If ecstasy is one of Farrokhzad’s major themes, the other is torment. Some of her best poems are poised uneasily between these two states of mind. In “Knot,” she writes:

I saw the warm wing of your breath

brush against my cold neck

as if a lost breeze rustled

in the wild thickets of my pain

. . .

That night your kiss scattered the drop of eternity

into the mouth of my love

While the rush of arousal is palpable, it’s worth paying attention to how the lover’s touch is described: as feeling both purposeful and indifferent, like the brush of a creature’s wing or a passing breeze. There is a sense, in the early poems, that male attention, while desirable, is untrustworthy, and that sex, while pleasurable, is devoid of love: “You never gave me your heart, although / my thirst had scalded your body like fire.” The mood grows warmer in the later work, where the addressee is a less-shadowy presence and connects with the poet on a deeper level: “The water of you filled the dry stream of my heart / The flood of you filled the riverbeds of my veins.” The change may have been due in part to Farrokhzad’s affair with Ebrahim Golestan, a writer and director whose studio she worked at. With his encouragement, she made The House is Black (1962), an astonishing documentary about a rural leper colony, now seen as a forerunner of Iran’s New Wave.

Two years before her death, Farrokhzad published “Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season,” her longest (nine pages) and most ambitious work. It abandons direct address for a fragmentary, collage-like approach, weaving together ominous images, scraps of conversation, vatic pronouncements, and troubled descriptions of a city—all in a manner that calls to mind European modernism. The central thread of the poem, whose main persona is a “woman alone,” is nature’s cycle of renewal and decay:

In the street the wind is blowing

and I am thinking about the flowers mating

about buds on thin anemic legs

and this exhausted, tubercular time

If more of “Let Us Believe” were this biting, Gray might have been justified in calling it a masterpiece, as she does in the introduction. While the poem is energetic throughout, and at times vividly morbid—“the man whose threads of blue veins, like dead snakes”—some of its sections seem murky, even emptily portentous, like a pale echo of “Prufrock”: “Will I ever again / comb my hair in the wind? / Will I ever again plant violets in the gardens?” Many of the later poems in this collection display a similar mixture of vigor and affectation. “Wind-Up Doll” is a blistering, if overheated, social critique of the patriarchy (“One can be just like mechanical dolls / and see the world with two glass eyes”); “Pair” is a tart, if pat, exercise in imagism (“Then two red dots / from two lit cigarettes / the tick-tock of the clock / and two hearts / and two solitudes”); and “Only the Sound Remains” is some kind of Dada (“Swollen corpses write the morgue’s thoughts / The coward / has hidden the loss of his manhood in the dark”).

Such criticisms should not distract from Farrokhzad’s achievement. Living through a period that promised more freedom than it offered, she found a literary form to register its contradictions. Her poetry embraces pleasure in the face of social censure, seeks a genuine spirituality while rebuking the cant of tradition, and pushes at formal boundaries, even if the results are uneven. Speaking urgently to readers of Farrokhzad’s generation, it also breathed new life into Iranian modernism, paving the way for younger writers to express themselves.

Ratik Asokan is a writer. He lives in New York.