Thomas Beller

Thomas Beller

The Victorians, “self-love,” and Brian Wilson: a history of the teen bedroom.

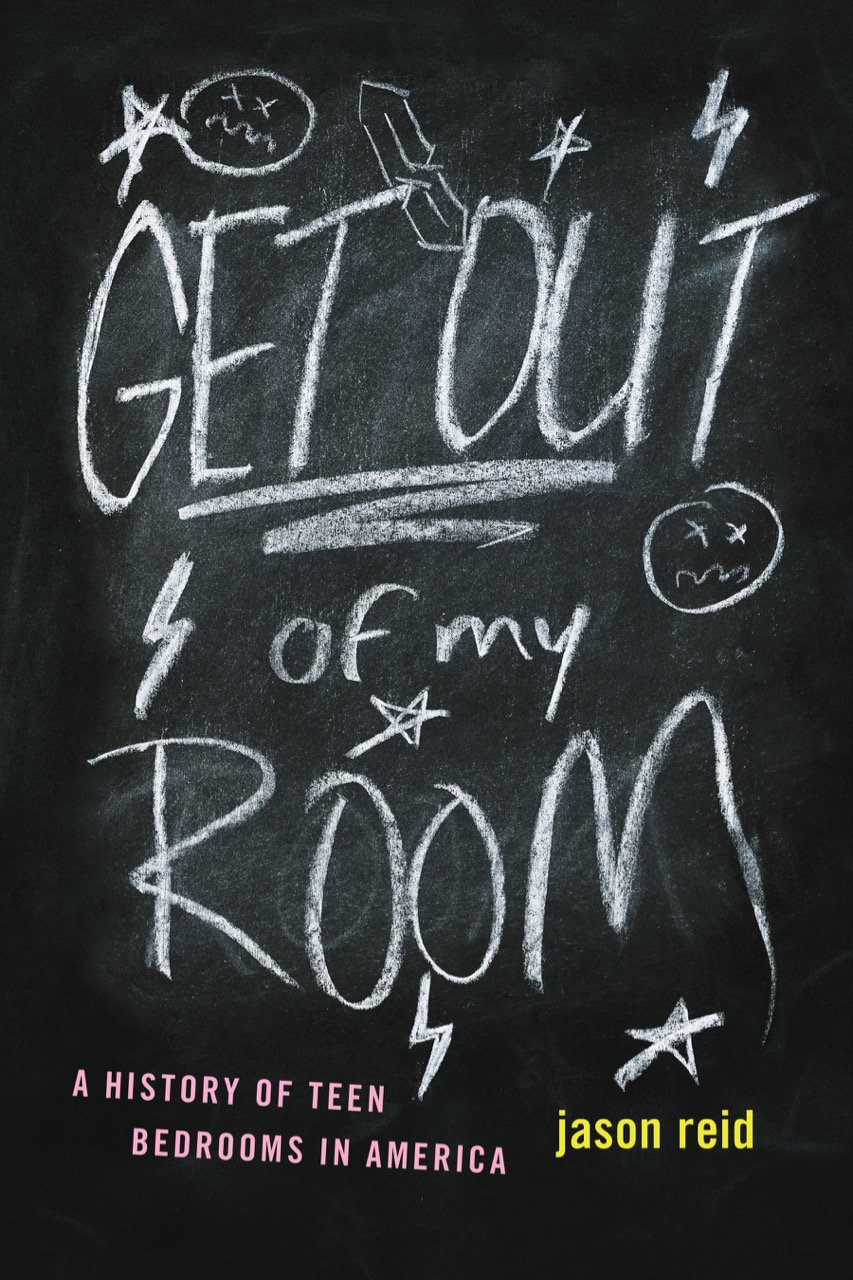

Get Out of My Room!: A History of Teen Bedrooms in America, by Jason Reid, University of Chicago Press, 299 pages, $45

• • •

1.

Not long ago, I bumped into the older brother of a childhood friend of mine. He was an impulsive, violent kid who had scared the crap out of me, back when I was in junior high school. He was just a couple of years older than us, a relatively small age gap, but significant when you are thirteen. I had gone to great lengths to avoid him in his own apartment when I slept over.

Fortunately, each brother had a room of their own. After our initial surprise of recognition and the pleasantries that followed, I asked about a memory I still had from one of my rare visits to his room. It was of a big concert poster on the wall.

“I still think about it,” I said. “This enormous concert poster with four panels, each with a shot of the band. I remember thinking it was very cool but now I can’t recall the band. Was it Led Zeppelin?”

“No. The Stones,” he said, adding, with a tiny glimmer of violence that I recognized from long ago, “we were a Stones household.”

I loved that line. And I immediately recognized it to be true. There was a framed version of a Stones tour poster of 1973 in my friend’s room, the airplane with the famous logo of those lips on its tail. Now I remembered that his brother had images of Mick, Keith, Charlie, and Bill, live in concert, on the wall of his room.

They lived in the Dakota, at Seventy-Second Street and Central Park. The Stonesness of that household was in some strange way further affirmed by juxtaposition with the building’s most famous resident at the time, John Lennon. Coming and going from the Dakota in those years meant passing a benign encampment of Lennon groupies sitting next to the building’s entrance at all hours. Going to my friend’s house in the Dakota was like entering a kind of umbilical tunnel that connected the Lennon groupies on the sidewalk and my friend’s Stones bedroom, a kind of free-trade zone of adolescent consciousness protected from the white noise of adulthood just beyond its parameters.

2.

Jason Reid, an assistant professor of history at Ryerson University, has written a book, Get Out of My Room!: A History of Teen Bedrooms in America, that I hoped would concern itself with the intimacies that occur in said rooms. But for a book with such a floridly intimate subject, it’s pretty dry. Its primary focus is less on what happens in these rooms than on the parents and adults who fret and speculate about what goes on behind their closed doors. It’s also the story of how society evolved in a way that made such protected spaces possible and desirable.

Reid begins in the early nineteenth century, when household quarters were cramped and chaotic. People slept higgledy-piggledy in the same beds. Parents, Reid explains, regarded “children as miniature adults who were expected to work and form a family at a relatively young age.” But then came the Victorian era, when childhood as we understand it—as a time cloistered apart from adulthood—was more or less invented. Living arrangements had to adapt to what was, in a sense, a new species in the home. It was also a time when families grew smaller. The average American family had about seven children in 1800. By 1900 it was 3.6.

In the urbanizing Northeast, in particular, people could afford to make spaces for children—nursery, playroom, and eventually a separate room for the household’s teenagers. It was in this region that education was most highly prized, and a room of one’s own was seen as a boon to the act of studying and the development of an autonomous self. In 1854, an influential reformer named O.S. Fowler wrote, rather optimistically: “If each [child] had a room ‘all alone to themselves,’ they . . . would feel personally responsible for its appearance, would feel ashamed of its disarrangement, would often find themselves alone for writing and meditation.”

“Self-love” is the serpent in this solitary garden, and it winds its way through the book. The words first appear on page 17. The menace is still going strong on page 168, in a section called “Teen Sex”: “One of the most pervasive fears associated with the teen bedroom,” Reid notes, “was predicated on the idea that it served as a venue for various types of sexual activity, most notably masturbation.”

It’s not that I expect an academic treatise to deliver Alexander Portnoy abusing the liver his mother had asked him to buy in the afternoon so she could cook it for that night’s dinner, but I find passages like the above challenging. Academic writing is the white noise of adulthood in its most sibilant form.

Reid read a lot of Spin magazine from its late 1980s and 1990s heyday and I enjoyed those citations, perhaps because I recognized them. Brian Wilson, who wrote the “own room” anthem, “In My Room,” is given an entire chapter. He is presented as a case study in the complicated motives and consequences of teenagers indulging in a wish for solitude. As a teenager, Wilson sought refuge from a horribly abusive father in his own room, where he could roll out of bed and play the piano. In the early 1970s, after his success with the Beach Boys, he retreated to his own room, literally to his bed. He later claimed that during this period he stayed in bed for four years straight, snorting cocaine and hiding under the covers.

3.

I was an only child with my own room. I usually closed the door. When my mother wanted to talk to me, she would knock. The great tension surrounding my need for privacy in those years wasn’t sex, which, though it was never said directly, I sensed to be permitted. It was drugs, which were not. For a while I took the trouble to exhale smoke into a balloon, which I would tie up and set free out my window, watching as it drifted away on the breeze. I loved that room and still do, though I rarely experience the pleasure of its solitude. I teach—and live—in New Orleans, but I come up to New York to live in that room for the winter holidays and much of summer vacation. Except it’s no longer my room, exactly. It’s now the headquarters of my whole family—a wife and two little kids, living higgledy-piggledy all over each other in cramped quarters.

Thomas Beller is the author of four books, most recently J.D. Salinger: The Escape Artist, which won the 2015 New York City Book Award for biography/memoir. His fiction has appeared in Best American Short Stories, The St. Ann’s Review, Ploughshares, and The New Yorker. A founder and editor of Open City Magazine and Books from 1990 to 2010 and the website Mrbellersneighborhood.com, he is currently an associate professor at Tulane University.