Hannah Black

Hannah Black

Days of Our Afterlives: a sitcom’s third season goes Down Under.

Kristen Bell as Eleanor in The Good Place, episode 304. Photo: Colleen Hayes/NBC. © 2018 NBCUniversal Media, LLC.

The Good Place, created by Michael Schur, NBC

• • •

Even in a golden age of television, The Good Place stands out for both its unusual ambition and its fidelity to sitcom tradition. Created in 2016 by Michael Schur, whose previous work includes Parks and Recreation, it bears some of the hallmarks of this earlier success: a precise balance of realism and absurdity, educational themes, and a slightly evil blonde lead.

The Good Place may or may not be intended as a loose adaptation of Sartre’s 1944 play No Exit, but it closely resembles one. In Sartre’s existentialist drama, hell is a stuffy drawing room where a coward, a home-wrecking lesbian, and a femme fatale torment one another for eternity. In The Good Place, a narcissist, a fool, a nihilist, and a prevaricating philosopher are brought together in the afterlife to make themselves unhappy. Sartre’s play is most famous for a line uttered by one of its lost souls: “Hell is other people.” But elsewhere the same character chides another, “Alone, none of us can save himself or herself; we’re linked together inextricably.” It is this second meaning of Sartre’s interest in mutual interdependence, as much as the first, with which The Good Place concerns itself.

Jameela Jamil as Tahani, Kristen Bell as Eleanor, Manny Jacinto as Jason, and William Jackson Harper as Chidi in The Good Place, episode 304. Photo: Colleen Hayes/NBC. © 2018 NBCUniversal Media, LLC.

The third season, which began airing in late September, finds the show’s quartet of central characters—Eleanor (Kristen Bell), Chidi (William Jackson Harper), Tahani (Jameela Jamil), and Jason (Manny Jacinto)—back on Earth and living in Australia, where they are all participating in a study on ethics. For the previous two seasons, which unfolded in the afterlife, they have technically been dead. In this season, they reapproach the show’s broad central question—something like “what does it mean to be good?”—from the perspective of the living.

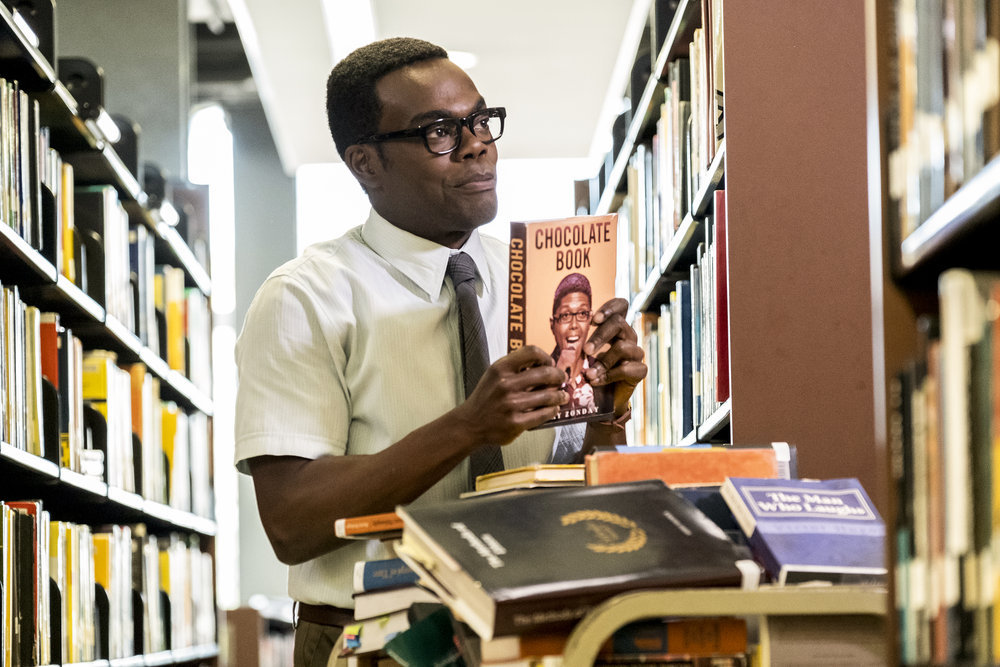

William Jackson Harper as Chidi in The Good Place, episode 301. Photo: Justin Lubin/NBC. © 2018 NBCUniversal Media, LLC.

Chidi, an ethics professor, has guided the group’s moral improvement since the first season, despite his own sin of chronic indecision. His central texts are drawn from moral philosophy; the theories of Plato, Kant, and Kierkegaard make cameos, and there are references to works by contemporary ethicists such as Philippa Foot’s classic “trolley problem” and T. M. Scanlon’s 1998 book on morality, What We Owe to Each Other. When Michael (Ted Danson), a helpful demon, shows up on Earth to guide Eleanor back to the path of righteousness, he quotes the latter book. This leads her to binge-watch ethics lectures on YouTube and eventually meet Chidi again, as if for the first time—the characters knew each other in the afterlife but have forgotten everything by the start of both the second and third season, and have to get to know each other again. The show’s habit of constantly finding ways to reshuffle the central group’s relations to each other is one of its key pleasures. Plot arcs are less “will they fall in love?” and more “will they remember that they fell in love already?”

Ted Danson as Michael in The Good Place, episode 305. Photo: Colleen Hayes/NBC. © 2018 NBCUniversal Media, LLC.

The Good Place’s worldview has the same gaps as its guiding form of philosophy: neatly limiting its scope to individual ethical choice, it avoids messy encounters with the structuring brutalities of capitalist society. And yet through its deconstruction of the paradise it begins with, the show seems to reach beyond the limitations of its reading list.

In the first season the afterlife is something like a liberal dream of Canada: overbearingly smug, multiethnic without any mention of race, and nobody can remember what class is. Its vacuous moral code is also that of the wealthy: stealing is bad, civility is good, philanthropy is the height of human kindness. Eleanor is an amoral dirtbag placed in this glutinous heaven for reasons that only gradually become clear. She doesn’t belong, and the evidence is that she is selfish and libidinal. For example, she shamelessly overindulges in free drinks and shrimp at a party; the other Good Place residents seem to have been so well-fed in life that they are politely unexcited by sudden, infinite abundance. Only the bourgeois go to heaven. Of course, all is not as it seems.

Kristen Bell as Eleanor in The Good Place, episode 104. Photo: Justin Lubin/NBC. © 2016 NBCUniversal Media, LLC.

But the mystery of how an image of life so lacking in interest or joy could be construed as an infinite reward in death doesn’t get fully cleared up until the end of the first season. The second season presents an exuberant vision of hell. And by the third, we’re back here on Earth.

According to this show, the differences between hell and Earth have been overstated. Just like in No Exit, hell’s main tortures are psychological rather than physical. Although in The Good Place we also get glimpses of fiery demons and hear about hell bears with several mouths, the torments are generated through the dead’s confrontation with their own meanness, banality, and entrapment in childhood pain. When all the demons of hell show up, they demonstrate how evil they are by texting nonstop, farting, and dancing to “Who Let the Dogs Out?” A world whose entire experiential register runs from the heights of a great date to the lows of bad customer service is the structure not just of The Good Place’s imaginary but also in general that of the sitcom, the great American form.

William Jackson Harper as Chidi, Kristen Bell as Eleanor, Manny Jacinto as Jason, and Jameela Jamil as Tahani in The Good Place, episode 212. Photo: Colleen Hayes/NBC. © 2017 NBCUniversal Media, LLC.

The characters in the show find themselves in an antagonistic relationship with the heavenly bureaucracy that prevails in their world, in which a points-based system calculates the worth of human lives as a series of moral inputs. As the show develops, we watch them in the process of turning away from this algorithmic pseudo-ethics in favor of an emphasis on the value of good-natured collectivity. The latter is familiar from Schur’s other shows: The Office, for example, where Schur was writer and producer, broke with the grim UK original by transforming the characters into fundamentally nice, kind people. The Good Place’s moral lessons circle around something like W. H. Auden’s labored-over phrase, “We must love one another and die.” These characters have already died, and now must learn to love each other, though the questions of love and death’s various mediations (class, race, gender, ability) are left untouched. Despite some jokes that reveal familiarity with the current zeitgeist’s relation to history—waiting for a table at a USA-themed restaurant in Sydney in a third-season episode, the group is offered the “manifest destiny package”; for a small price the server will free up a table by kicking another party off it—the characters bear race/class/gender differences as if they were just charming character quirks. In this respect the show is trapped (perhaps the sitcom as a form is trapped) in a long 1990s.

William Jackson Harper as Chidi, Kristen Bell as Eleanor, Jameela Jamil as Tahani, Manny Jacinto as Jason, and D’Arcy Carden as Janet in The Good Place, episode 303. Photo: Ron Batzdorff/NBC. © 2018 NBCUniversal Media, LLC.

But its creators seem aware of this. Why else would the show provide a vision of the afterlife so signally lacking in otherworldly transcendence? In this world, the drippiest bourgeois fantasies of goodness, the furthest horizon of most TV dreams, turn out to be demonic tortures. Eleanor’s supposedly relatable selfishness—a sitcom-character trope peddled everywhere, from Seinfeld to Insecure, perhaps because people who don’t care about others are more fun to laugh at—is played for laughs as usual, but the show so far has been the arc of her struggle to overcome it. Deeply fluent in the conventions of the sitcom, Schur has reimagined it as an existential morality play.

Hannah Black is an artist and writer from the UK. She lives in New York. She has previously written for Artforum, the New Inquiry, Afterall, Texte zur Kunst, and a number of other publications. Recent exhibitions include Some Context at the Chisenhale Gallery in London and Anxietina at the Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva.