Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

In elegizing her mother, Mexican poet Coral Bracho finds new direction.

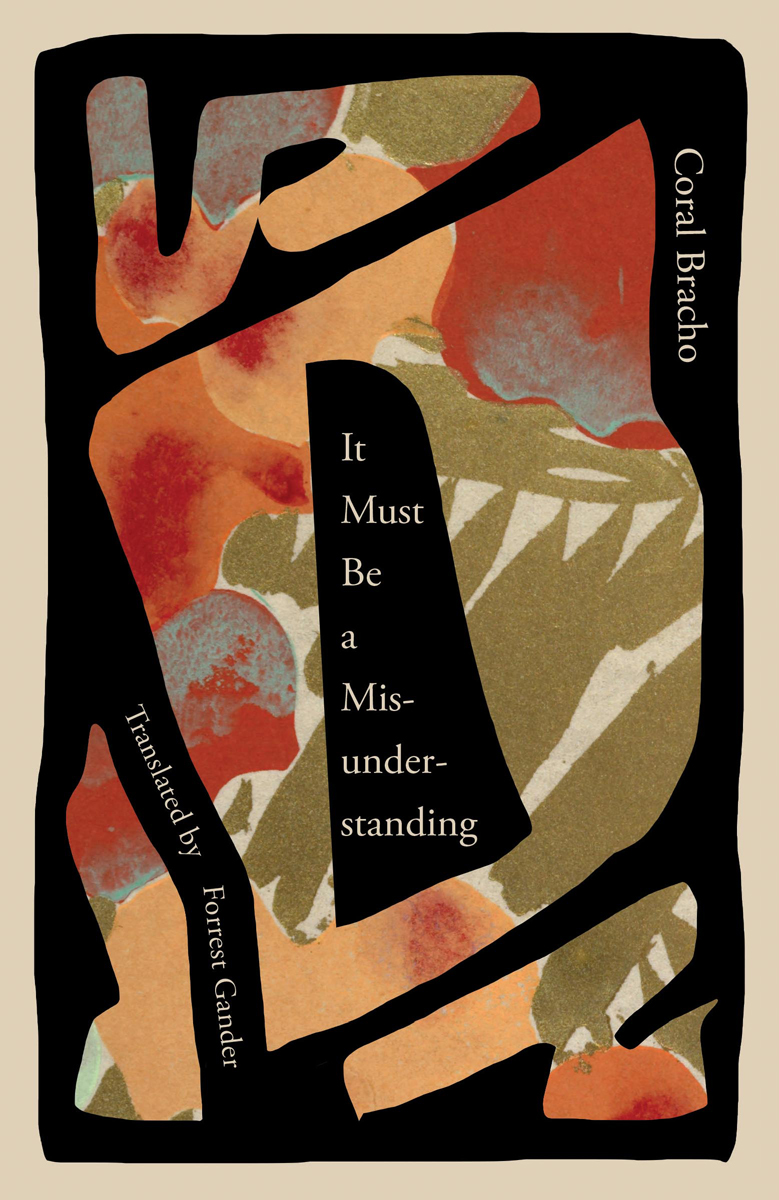

It Must Be a Misunderstanding, by Coral Bracho, translated by Forrest Gander, New Directions, 135 pages, $16.95

• • •

In the work of Mexican poet Coral Bracho, sensations hurtle toward us at whiplash speed. We’re sure we’ve seen, heard, touched something, even when we don’t know for certain what it is. Where her imagery is most opaque, the sounds of language offer their own visceral pleasures, a compensation for our bewilderment: “Sink into this springy calm,” she beseeches us in a characteristic passage from her 1981 book Being Toward Death, “into this mild emulsion of essences, of lubricious earth; / entwined, lose yourself in the algae . . .” The solitary human voice—that mainstay of the lyric—is hard to isolate, its melody swallowed up in lush sheets of harmony. The poet’s tone is authoritative, but she subjugates herself to the environment, an ecology so intimidatingly dense even the most capacious mind can’t take it in.

Bracho’s previous stateside publication was 2008’s Firefly Under the Tongue, a career-spanning anthology made up primarily of tremulous odes to nature (Gerard Manley Hopkins strikes me as an English-language precursor). These poems, dating back to her debut in 1977, treat earthly experience as if it were one vast erogenous zone. There’s a lot of caressing and embracing and vibrating in these pages, thresholds being crossed and things catching fire—but the desiring subject is relegated to the shadows. If the speaker seems at home in the world’s unknowability, the reason is simple: it gives her pleasure. But what happens when such an externally oriented poet is thrown back into herself? How does she cope when unknowing is no longer a state of rapture but one of ordinary suffering?

It Must Be a Misunderstanding is a potent answer to these questions. Dedicated to her mother, who died of complications from Alzheimer’s, Bracho’s latest collection charts a path through the stages of the disease, the closest the poet has ever come to such melodrama-friendly subject matter. But unlike so much grief literature—which can so easily flatter the self, its capacities for steadfast love and white-knuckle resilience—this new work isn’t consumed by the usual emotions of a bereaved individual. That remains true even in moments depicting the mother’s breakdowns and outbursts, as when she loses her temper at a bouquet of flowers “with two or three dry, faded blooms / among so many others freshly opened”—one of several instances where we see an exquisite, unified whole that’s been blemished or broken.

The book meets the mother’s condition on its own terms. Instead of dwelling on what can never be recovered, Bracho identifies something gained, a new angle from which to contemplate the limits of knowledge that have long preoccupied her. This heightened perception emerges from not just a psychological deprivation but a material one. In Firefly, life-forms are named with an exoticizing specificity: ceiba trees and tabachin trees, gardenias and magnolias, sargo and jellyfish. But in It Must Be a Misunderstanding, Bracho’s repertoire of images is pared down to everyday symbols like doors, shadows, and snow—commonplaces of the elegy.

The setting is not a teeming, fertile landscape but a sterile residential care facility, where “all the hallways are white, / and they seem to be padded.” Quotidian objects loom as large as any human presence, and they acquire an eerie resonance by being matter-of-factly out of place. Early on, the mother describes a row of chairs planted “right in the middle of what I want to say”; later, she contemplates storing her suitcase in the shower. In the most surreal passages, things morph without warning—black curtains become a forest; a man’s suit is the face of a wall—and our senses get synesthetically tangled.

The poems of Bracho’s early career tend to have a flowing, vine-like shape, but here her sentences are mostly constricted within a few short lines. As if to counteract the chaos, the poet establishes an orderly, predictable structure, alternating between baffling sequences of illogic and insights delivered in the daughter’s measured voice. When we’re trapped inside the elder heroine’s subjectivity, everything feels new and unsettling. The mother is besieged by “unanticipated tenants” that have “no likeness,” including a bird pecking asphalt at her feet—a vision she regards as if it were an extraterrestrial sighting. Metaphor—a linguistic device that relies on memories, past objects that can be compared to present ones—necessarily breaks down. But the poet confronts the evidence of collapse with an all-embracing serenity. Her role here is to piece together meaning, however provisional it may be, wherever she can find it.

Sometimes her conclusions double back on themselves. The book has a stammering cadence built on reversals and qualifications: “She knows that she knows, and she knows / that she doesn’t know”; “she’s trying to laugh. / Or not to laugh.” At other times, Bracho lands on an aphorism that, amid the perplexity that surrounds her, has the soothing, ringing quality of a melodic refrain. Where her previous work reveled in description, here she responds to the “disquieting, incomprehensible / strangeness” of the world with philosophical statements: “The gestures of others tell us / what we should feel”; “Meaning is what accommodates things / wherever they feel / they can be.” These lines evoke the kind of certainty she finds not in language but in music, which Bracho describes as “a clear and beautiful mode of speaking.” “A note is / what it is,” she declares; so, too, is truth, she seems to tell us.

Like Firefly, It Must Be a Misunderstanding was translated by the American poet Forrest Gander, whose sensibility is perfectly suited to Bracho’s. The two share a deep investment in the natural world; his work is often associated with a literary subgenre known as “ecopoetry.” Furthermore, like Bracho, Gander is a masterful observer of familial intimacies. His devastating book Be With (which won a Pulitzer Prize in 2019) eulogizes his deceased wife and mother, the latter of whom also suffered from Alzheimer’s. Bracho’s elegies are less palpably heartbroken than Gander’s, and one imagines that in her work he’s found a different model for communing with grief. Our losses have a way of locking us inside ourselves. But in It Must Be a Misunderstanding, Bracho endeavors against the odds to forge an “avid, intimate alliance / with the species,” keeping her eyes on the vanishingly few things that bind her to someone whose reality she’s no longer privileged to share.

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, the New Yorker, NPR Music, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.