Leo Goldsmith

Leo Goldsmith

An extensive program looks back at five decades of avant-garde film.

Lawrence Jordan, Duo Concertantes.

“Canyon Cinema 50,” Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, New York City, through April 29, 2018

• • •

What is an underground, and how do you build one?

These days the internet’s open field seems to make all things visible—if not entirely accessible. A half century ago, the situation for independent artists was much trickier: in the domain of film practice that might variously describe itself as “independent,” “experimental,” or even “avant-garde,” getting films made, let alone seen, demanded the building of something more than a venue. It necessitated a whole new infrastructure.

Since 1967, the Bay Area film distributor Canyon Cinema has been one important node in the expansive network of American underground, experimental, and independent cinema, and it’s now celebrating its golden anniversary with “Canyon Cinema 50,” a touring slate of films assembled by the independent programmer David Dinnell.

In its 1992 catalogue, Canyon declared itself, rather modestly, as “a democratic, non-discriminatory outlet for the distribution of independent film . . . with no restrictions as to form, content, length, etc.” This perhaps makes the project sound rather vague, but then again Canyon’s notion of an “underground cinema” has always been defined more by its mode of circulation than any particular style or aesthetic program. Following the model set out by Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16, the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, and even Warhol’s Factory, Canyon Cinema was part of an emerging alternate media ecology in the mid-1960s that did more than advocate for a different kind of movie. It advanced a distinct and independent infrastructure for producing, distributing, and exhibiting films—with the artists themselves at its center.

Canyon began its life humbly—as an itinerant East Bay microcinema founded by the filmmaker Bruce Baillie around 1960. Setting up a projector and an Army-surplus screen in his backyard or at the occasional restaurant or coffee shop and giving out free popcorn, Baillie was soon joined by filmmaker Chick Strand and Film Quarterly editor Ernest “Chick” Callenbach in hosting community screenings of experimental—or simply off-piste—work around the Bay. Canyon soon expanded its operations to include Cinemanews, a critical publication on the artists in its orbit, and, by 1967, began the distribution of works by its members, all managed by a board of directors that included, in its first iteration, the filmmakers Ben Van Meter, Robert Nelson, and Lawrence Jordan.

Chick Strand, Mujer de Milfuegos.

Aptly, the “Canyon Cinema 50” programs provide a glimpse of the work of these founding members. Baillie and Strand are represented with two exquisite examples of their idiosyncratic experimental ethnography, both filmed in Mexico: Baillie’s Valentin de las Sierras (1968), a tightly framed reverie based on the filmmaker’s encounter with a blind balladeer in Jalisco; and Strand’s Mujer de Milfuegos (1976), an erotic, hallucinatory portrait of witchy ritual that magic(k)ally collapses birth, sexuality, and death at both the sonic and imagistic levels. Jordan, a sometime protégé of Joseph Cornell, is showcased here with his 1964 film Duo Concertantes, an example of his distinctive surrealist cutout animations, which anticipate Terry Gilliam’s similar work for Monty Python by some years.

Charlotte Pryce, A Study in Natural Magic.

These programs also offer a wide sampling of formal abstraction and associative montage: from the intricate montage-in-the-frame works by Pat O’Neill and Janie Geiser to the quicksilver animated transformations of Robert Breer’s Swiss Army Knife with Rats & Pigeons (1981) to Phil Solomon’s richly textured treatment of his own celluloid home movies in The Snowman (1995) to Tomonari Nishikawa’s precisely rendered onslaught of single-frame images in Market Street (2005). Individual programs—such as the first, “Studies in Natural Magic”—find subtle concordances across an array of diverse work. Spectral in-camera coronas make appearances in both Saul Levine’s Light Lick: Amen (2017) and Charlotte Pryce’s A Study in Natural Magic (2013), the program’s namesake. Minutely observed plays of light and shadow reveal hidden hues and textures both in the viscous fluid of a dime-store glitter wand in Christopher Harris’s 28.IV.81 (Bedouin Spark) (2009) and in the inky, voluptuous smoke clouds of Peter Hutton’s Boston Fire (1979). Elsewhere, the aggressive intersection of sound and image yields maximalist experiments in densely compacted meaning, such as the headlong assault of Abigail Child’s found-footage masterwork, Mercy (1989), or John Smith’s Associations (1975), in which the filmmaker atomizes words into fragments that he gleefully reconstructs as homophonic image-signs. The film’s title is expressed through the images representing “ass,” “sew,” “sea,” “eight,” and “Asians”—and the film maniacally persists in this elaborate structuralist joke for seven minutes until giving up with a resigned “Oh, bucket!”

John Smith, Associations.

Rather than dwell nostalgically on the usual avant-garde tropes and traditions—or focus solely on the work of the distributor’s undisputedly illustrious founders—the programs here give a sense of Canyon’s capacious, “non-discriminatory” character. Very much in evidence is the distributor’s commitment to personal cinema made by women in a field often dominated by the figure of the straight, white, male artist—a priority signaled from the start by Strand’s inclusion among its core founders. The earliest film to be screened—which actually predates Canyon’s official existence—is Sara Kathryn Arledge’s peculiar 1958 What Is a Man?, a hodgepodge of social satire, modern dance, and Joycean wordplay. Among the more recent offerings, Jodie Mack’s Point de Gaze (2012) is a silent work composed entirely of close-ups of densely woven Belgian lace, sensuously engaging with its materials while also subtly feminizing the often masculine domain of the abstract film. JoAnn Elam, too, makes a timely intervention in her 1982 film Lie Back & Enjoy It: accompanying a continually looped and reframed found image of a classic movie starlet, the film’s soundtrack features a conversation between a male filmmaker and his female partner, who vocally objects to his attempt to make a film out of her life by pointing out to him, at length, the power dynamics between men and women, and between filmmaker and subject. “Can’t a man make a film about a woman?” he asks pleadingly. The answer: “No.”

Jodie Mack, Point de Gaze.

Alongside these are bona fide classics of American experimental film like Gunvor Nelson’s dizzying monochrome kaleidoscope My Name Is Oona (1969), Barbara Hammer’s brazen erotic reverie Dyketactics (1974), and Naomi Uman’s Removed (1999), in which the filmmaker tints and bleaches a ’70s porno to render the images of women as ghostly, white blurs. But the big surprises are found in the deeper cuts, such as Betzy Bromberg’s Ciao Bella or Fuck Me Dead (1978), a deliciously foul-mouthed discopunk love poem to the East Village, which intercuts sequences of strippers and Bromberg’s partner and child, all in varying degrees of nudity.

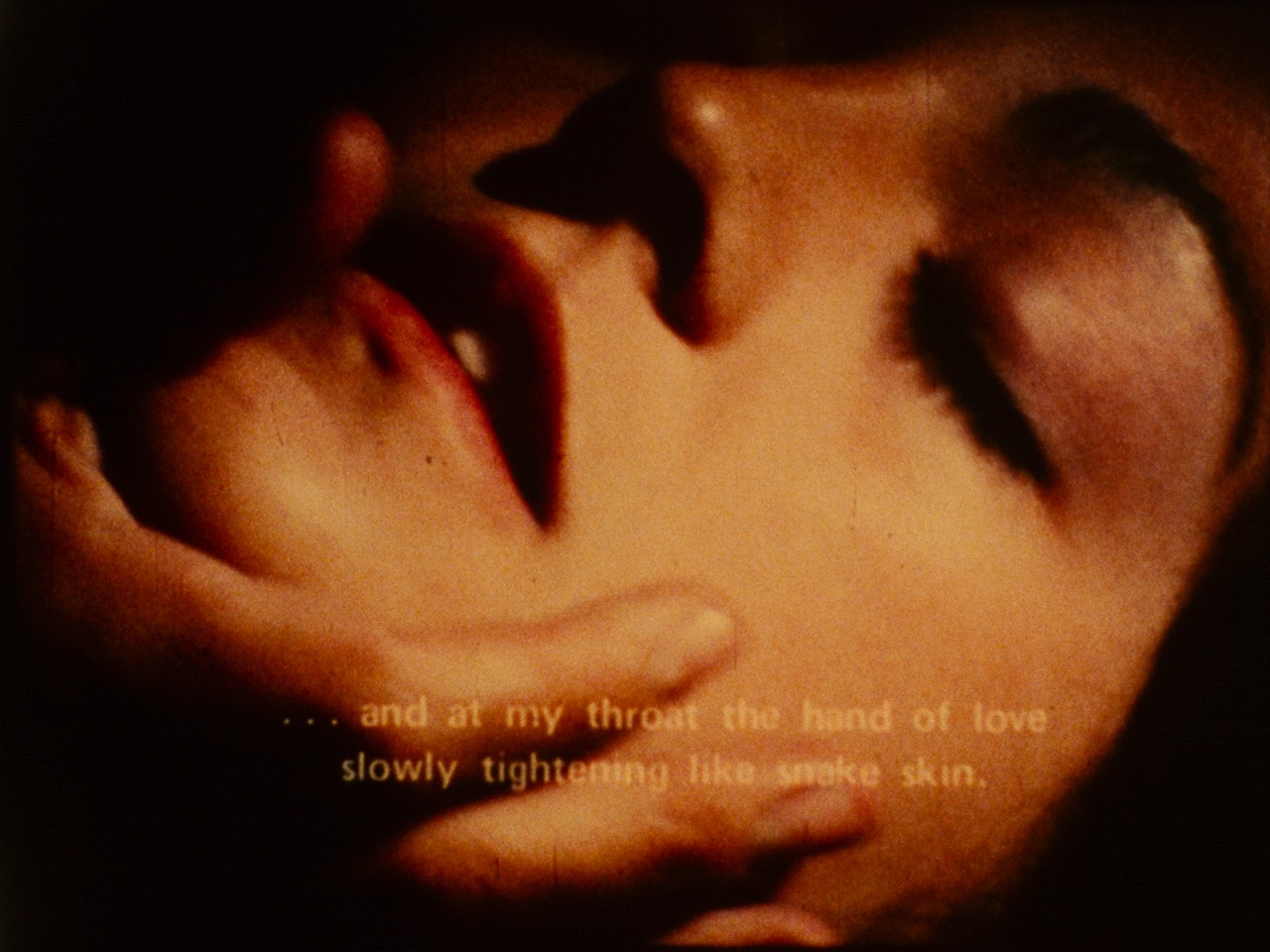

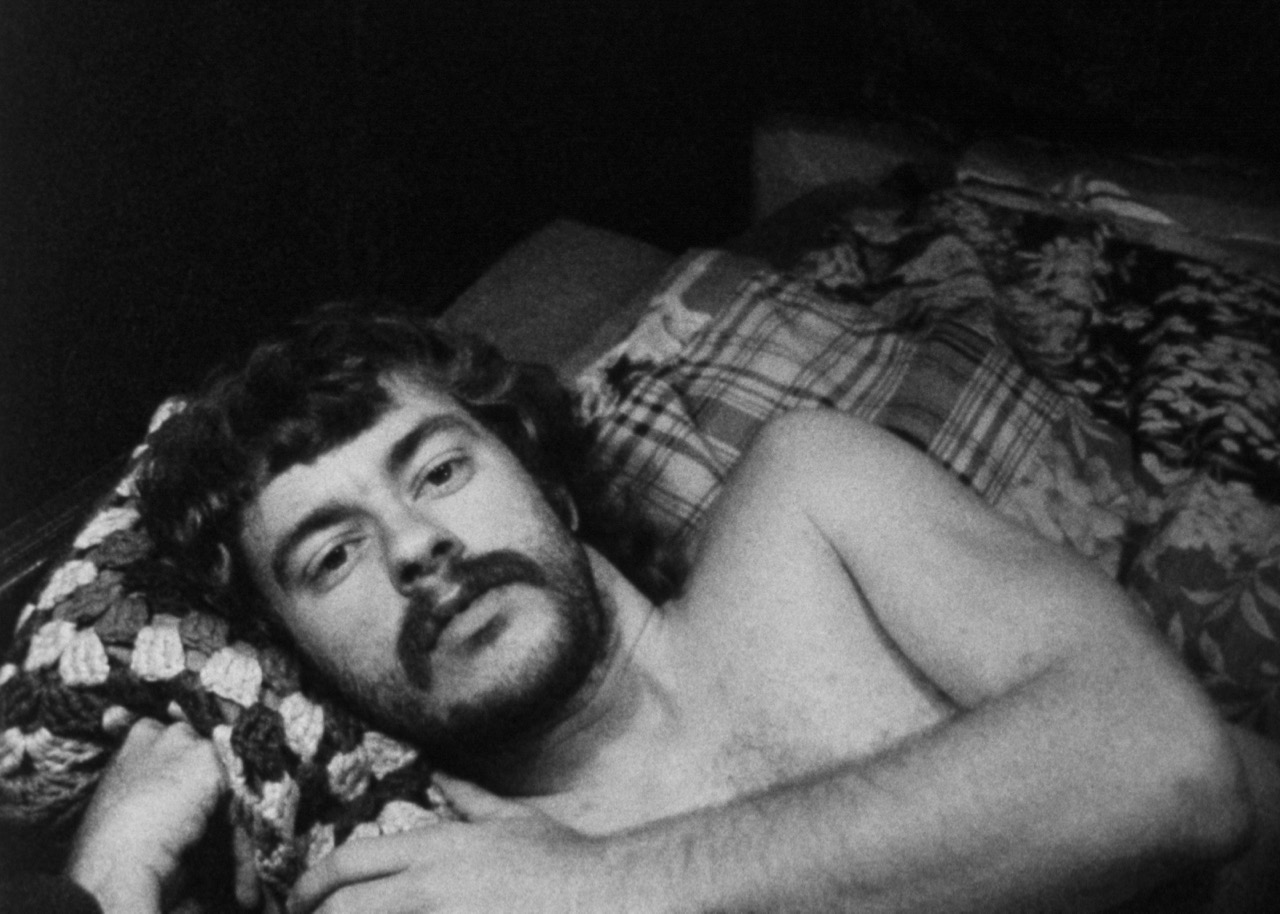

Curt McDowell, Confessions.

A similar polymorphous perversity guides Curt McDowell’s audaciously lewd and achingly sincere Confessions (1971), which begins with the filmmaker’s tearful, direct-to-camera coming-clean about all manner of sexual and narcotic transgression, before descending into a chaotic assemblage of interviews, carnivalesque hoopla, and gay and hetero hardcore. McDowell’s film, in many ways, encapsulates Canyon’s spirit of defiant independence, marked as it is by both a strident devotion to self-expression and a generous openness to the hybrid, the contingent, the unorthodox. Cauleen Smith’s extraordinary Chronicles of a Lying Spirit (by Kelly Gabron) (1992) captures this, too, with a playfully collaged mix of apocryphal autobiography and thickly overlaid text and image that stages the pseudonymous filmmaker’s struggle for self-representation amid a marginalizing mainstream image-culture. Her statement of purpose, delivered at the film’s midpoint, could well be inscribed on the lintels of Canyon’s doorpost: “I know now that the only way I’m gonna get on TV is to make my own goddamn tapes and play them for myself.”

Leo Goldsmith is a writer, teacher, and curator based in Brooklyn, New York. He coedits the film section of the Brooklyn Rail, and writes about art and film for such publications as Artforum, art-agenda, Cinema Scope, and the Village Voice. He is currently an adjunct lecturer at New York University’s Center for Experimental Humanities and Feirstein Graduate School of Cinema at Brooklyn College.