Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

An artist looks at the complexities of contemporary Indigenous life.

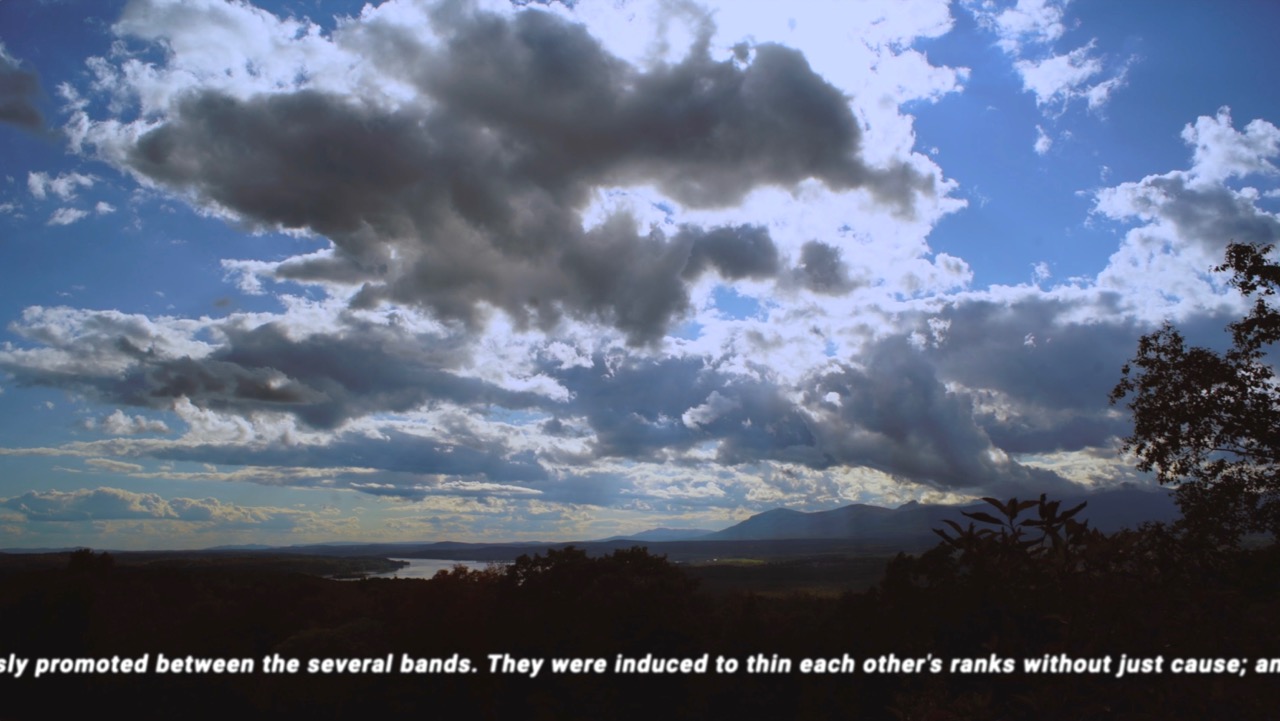

Sky Hopinka, Dislocation Blues, 2017 (still). HD video, stereo, color, 16 minutes 57 seconds. Courtesy the artist.

Sky Hopinka: Centers of Somewhere, curated by Lauren Cornell, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, through January 10, 2021

• • •

Sky Hopinka’s 2017 video Dislocation Blues, on view now at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College as part of Sky Hopinka: Centers of Somewhere, introduces us to Cleo Keahna. The young, Anishinaabe storyteller speaks about finding his place among those who took part in one of the most high-profile instances of Indigenous resistance to US government attacks on Native sovereignty in recent years: the Dakota Access Pipeline protests at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in 2016. Keahna reflects on the process of connecting with thousands of Native activists from hundreds of federally recognized tribes as one in which his queer body ceased to matter and his ego melted away—a movement “from me to us.”

Over the course of almost seventeen minutes, close-ups of Keahna, speaking through the interface of Hopinka’s laptop screen, give way to other sounds and images—including other protesters, encampments along the Cannonball River, the panoramic landscape, processions, demonstrations, and amiable socializing. (Importantly, Hopinka doesn’t include direct shots of the oppressive forces of the US state, nor does he offer any description or overview of events; that’s research left for the viewer to do.) What results is not so much a documentary about a signal event but a set of intimate, fragmentary impressions by people, including the filmmaker himself, trying to make sense of what happened. When Keahna suddenly turns to Hopinka (invisible on the other side of the screen) and asks, “Do you think it’s accurate?”—asking whether the artist agrees with his assessment of what being at Standing Rock in those months was like—we hear an echo of the doubt, questioning, and vulnerability that run through Hopinka’s practice as a whole.

Sky Hopinka: Centers of Somewhere, installation view. Photo: Olympia Shannon.

The exhibition at Bard includes three of the artist and filmmaker’s lush single-channel videos, a series of etched photographs, and calligrams in the form of wall vinyls, all made since 2015, as well as a newly commissioned three-channel video installation, Here you are before the trees (2020). What links all of these is a predilection for layering voices, languages, temporalities, and modes of analysis, the accumulation of which seeks to make sense of the complexities that mark contemporary Indigenous life. Hopinka was born and raised in Washington State. His father, a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation, whose homelands are in Wisconsin, is a singer. His mother, descended from the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians whose traditional territory is in Southern California, is a dancer. They met on the powwow circuit, living the peripatetic life of performers. Hopinka went to graduate school in Wisconsin, not far from the Ho-Chunk territory where his grandmother lived until her death in 2018. Hopinka is a student and teacher of Chinuk Wawa, an almost extinct Indigenous language spoken in the Pacific Northwest and in the process of being revived. He now teaches film and electronic arts at Bard College in the Hudson Valley, a region originally occupied by the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians, who were driven off their land and resettled near the Ho-Chunk in Wisconsin back in the 1830s. (The Ho-Chunk were, likewise, driven away from their homes in Wisconsin by the US government over the course of the nineteenth century, but kept making their way back.)

If this sounds complicated, it surely is—a hybrid mix of ethnicities, affiliations, and geographies that was and still is shaped by the colonizing force of the United States. The dislocation and relocation of Indigenous people from their land and the suppression of Native tongues were part of larger processes of cultural extermination that have been taking place over centuries. How to define one’s self, one’s place in the world, in light of this past and present?

Sky Hopinka, Jáaji Approx., 2015 (still). HD video, stereo, color, 7 minutes 39 seconds. Courtesy the artist.

It is perhaps no surprise, then, that movement and language occupy such a central role in Hopinka’s work. Jáaji Approx. (2015) centers on audio recordings the artist made with his father (jáaji in the Hočąk language of the Ho-Chunk) playing over images filmed through a car’s windshield as it drives down highways and backroads. The effect is that of father and son on a road trip; as the trip goes on, Hopinka’s father sings and tells stories about performing at powwows. There is no single chronological line to his narrative; there are no road signs or markers to help place us geographically; and at certain points the landscape flips, so that mountains and plains are where the vast sky should be, and vice versa. If Hopinka is trying to understand the distance that separates himself from his father, or to identify the things that bring them close together, or to define his own experience of Indigeneity, the subtitles give a gently comic gloss to their interaction: though his father was speaking in English all the time, his stories appear across the screen written out in International Phonetic Alphabet, some characters of which are used by Hočąk speakers. When you sound out the signs, it turns out that the words themselves haven’t been translated, just transliterated—English is presented as simply another way of speaking the language of the Ho-Chunk.

Sky Hopinka: Centers of Somewhere, installation view. Photo: Olympia Shannon.

The juxtapositions Hopinka relies upon in his single-channel videos are given new form in his three-channel installation Here you are before the trees, which was commissioned by Bard College and explores the Indigenous history of the land on which it sits through the prism of Hopinka’s own lived experience. The piece starts with text, on each screen, announcing what we will be seeing: “This is the Mahicannituck,” “This is the road,” “This is the Waaziija.” The titles give way to images of the Hudson River (the Mahicannituck), the lands of the Ho-Chunk Nation (the Waaziija), and the travel along highways linking the two. The relationship between those places is both deeply personal for the artist—the Waaziija is where Hopinka’s grandmother lived (she makes an appearance in the video), and the Mahicannituck is just by where he now lives and works—and terribly historical, the result of the relocation of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians to Waaziija territories.

Scrolling across the bottom of the three screens is a transcription of an 1854 oration by John Wannuaucon Quinney, addressing the colonists’ crime of ejecting people from their lands. Meanwhile, along with Hočąk songs and the sounds of the landscapes, we hear recordings of lectures by writer and activist Vine Deloria Jr. (from the 1970s) and scholar Renya K. Ramirez (from the 2010s) talking about how anthropologists and ethnographers pushed the idea of the essential connection of Indigenous people to their land as a way to further alienate the dislocated from their cultural identities.

Sky Hopinka, Here you are before the trees, 2020 (still). HD video, stereo, color, 3-channel, synchronous loop, 12 minutes 44 seconds. Courtesy the artist.

In the face of this history of forced migration, and with images of a recent road trip between the Mahicannituck and the Waaziija rolling by on screen, Ramirez can be heard proposing the idea of a “Native hub”—a way of thinking of place that takes into account the movement of people, languages, affiliations, and identities, so that community comes into being wherever people gather, and so that Indigenous solidarity can persist. As if to underline the point, the images on the screens occasionally swap places, and sometimes dim, so that the road appears where the river should be, and the river appears where the Ho-Chunk lands were, and the Ho-Chunk lands replace the road, and so on, suggesting that geography is not a stable marker of identity, but neither is it beside the point. This work, along with so much else on view in Centers of Somewhere, proposes different definitions of belonging for peoples who have survived and persisted in the face of colonial erasure, and makes space for hybridity—as opposed to “authenticity”—as a defining aspect of Indigenous experience.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She is co-curator of Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, an upcoming retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; editor of Lorraine O’Grady’s Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2020); and a member of the advisory board of 4Columns. In 2020, she received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.