Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

A vast gallery show tackles the enigmatic musician and artist.

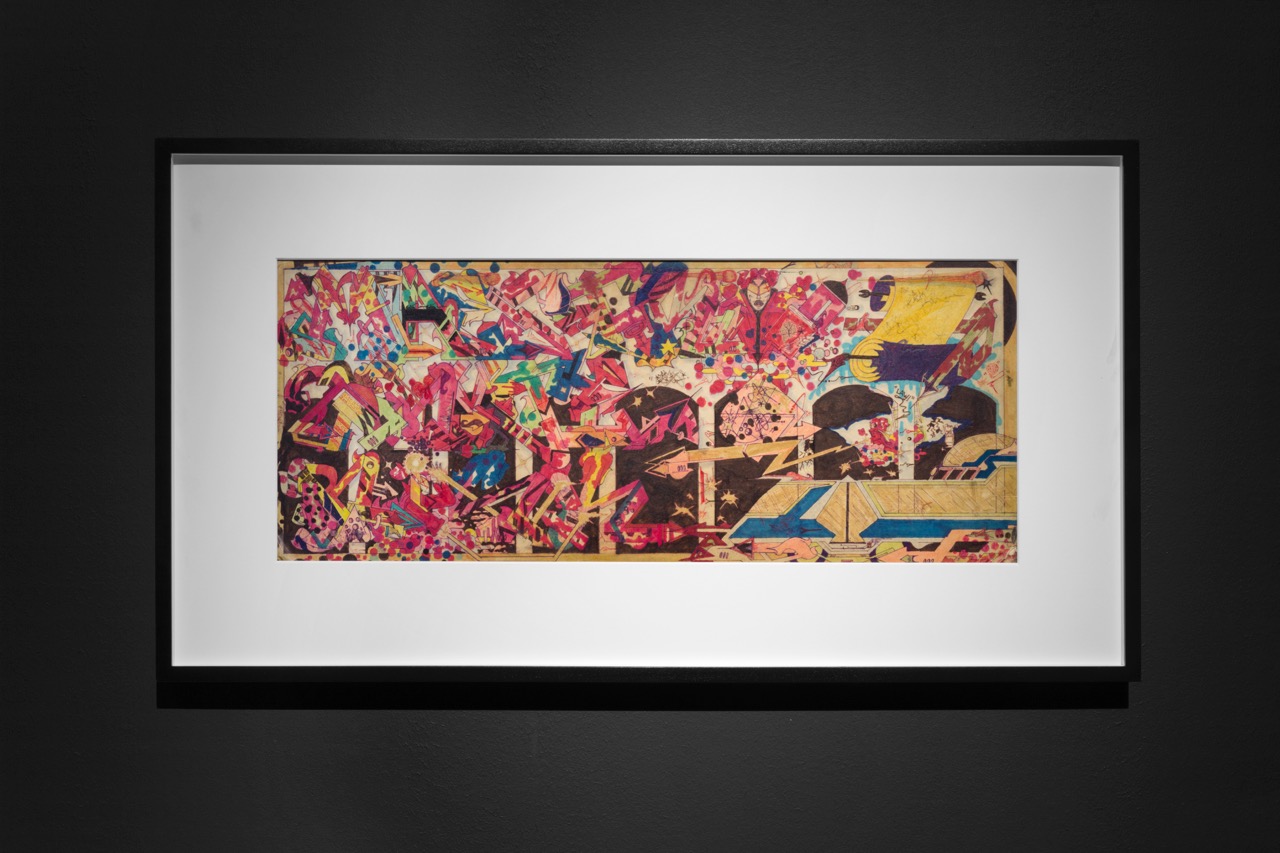

Keetja Allard, Rammellzee as Chaser the Eraser, 2002. Image courtesy Red Bull Arts New York. ©2018 The Rammellzee Estate.

RAMMΣLLZΣΣ: Racing for Thunder, Red Bull Arts New York, 220 West Eighteenth Street, New York City, through August 26, 2018

• • •

Rammellzee was inscrutable by design. The late artist, musician, and writer, who died in 2010 at the age of forty-nine, spent his life developing his own complex, fully formed mythos. He took on the name Rammellzee in 1979 (his real name is, to this day, a firmly held secret), and even the name looked like an art project; if you drew it out as he did (RAMM:ELL:ZEE), you could see the parallel lines and symmetry, rhythm and geometry in action. In his lower Manhattan apartment, which he called the Battle Station, he surrounded himself with his weirdly baroque creations: bizarre, vividly hued masks, hallucinatory graffiti murals, intricate junk sculptures, paintings, imposing sci-fi costumes that split the difference between Voltron and Japanese monster flicks, and numerous gnomic texts, including abstruse essays on philosophies he invented: “gothic futurism” and “ikonoklast panzerism.”

A staggeringly exhaustive retrospective, currently on view at the Red Bull Arts New York space in Chelsea, offers a fascinating plunge into the Rammellzee mythology. Two cavernous floors are densely packed with material; the lower floor looks inspired by the Battle Station. The show raises more questions than it answers, which is perhaps understandable: with Rammellzee, there weren’t any straight answers. “Art is an equation, just like Rammellzee is an equation,” he once said cryptically in an interview, without offering any solutions to the mathematics.

Rammellzee: Racing for Thunder, installation view. Photo: Lance Brewer. Image courtesy Red Bull Arts New York. All artwork © 2018 The Rammellzee Estate.

Rare video footage of Rammellzee’s musical exploits fill a back corner of the upper floor of the gallery. Though music was a mere blip in his resume, he left an unforgettable mark on hip-hop in its early days, and many people who have heard of Rammellzee think of him as a rap pioneer. The visionary 1983 single “Beat Bop,” made with K-Rob and Jean-Michel Basquiat, is now a classic moment in music history. The track—ten minutes of effortless flow over an utterly cool, minimal throb—sounds like it was made yesterday. Rammellzee, for his part, was already bored. Aside from a few scattered musical appearances, he went back to creating art at a furious clip, busily constructing his alternate fantasy universe. “We have Greek myths and Roman myths—we need an American one,” the music writer Chris Campion recalled Rammellzee saying, in a recorded commentary playable on one of the show’s many listening stations. That new myth didn’t emerge fully out of nowhere: in an interview with Greg Tate, published in The Wire in 2004, Rammellzee name-checked some ancestors and contemporaries, all strange in different ways: Sun Ra, George Clinton, the Hells Angels, Gene Simmons of Kiss, AC/DC.

Rammellzee, Maestro 2 Hyte Risk, 1976. Installation view. Photo: Lance Brewer. Image courtesy Red Bull Arts New York. All artwork © 2018 The Rammellzee Estate.

“New York City is a place of mysteries,” as a famous line in “Beat Bop” goes, and Rammellzee was one of them. Over his life, he helped make the city a more thrilling and enigmatic place. This was clear even as a teen growing up in Queens in the 1970s, when he was part of a loose crew of graffiti writers who famously “bombed” New York City subway trains, triumphantly blasting them in startling, colorful murals. His messages to the public were delivered in code, even then, and his raw talent was evident. Some of the most stunning pieces in the show are the intricately geometric graffiti murals crafted with marker on cardboard in the 1970s—the two-panel Evolution of the World (1979) and Maestro 2 Hyte Risk (1976). His early 1980s paintings show his style becoming looser: in The Knowledge of the Square, The Knowledge of the A, and Jams, all from 1982, spray-painted graffiti tags and thick stripes and dots of acrylic paint coalesce into a riotous, intuitive mess of color.

Rammellzee, Gulf War, 1991. Installation view. Photo: Lance Brewer. Image courtesy Red Bull Arts New York. All artwork © 2018 The Rammellzee Estate.

Nearby is Gulf War (1991), a dense, labyrinthine junk sculpture that is impossible to ignore. A giant Gulf gas station sign was sliced open in half, revealing its industrial insides. The guts of the sign were transformed by Rammellzee into a ramshackle world of technology and death, in an assortment of artfully arranged detritus: a makeshift laser disc player, rusted gears, glowing skulls, a plastic eyeball, a telephone, a model railroad set, plastic fans, military paraphernalia. Another nearby sculpture, hot-glued inside what looks like a busted-up briefcase, takes in more skulls and eyeballs, an array of “8” balls, news clippings, padlocks, nail polish, and bits of kitchen hardware.

Rammellzee, Letter Racers. Installation view. Photo: Lance Brewer. Image courtesy Red Bull Arts New York. All artwork © 2018 The Rammellzee Estate.

Letter Racers, a series of sculptures mounted onto toy cars and skateboards, and the Garbage Gods, samurai-inspired horror-movie apparitions constructed from urban debris, populate the bottom floor. The Letter Racers—which place individual letters of the alphabet on wheels—again showcase Rammellzee’s focus on the written word. From his earliest days with graffiti writing to his numerous essays to his flair with wordplay on the mic, the study of language—and its links to fiction, hidden meanings, mysticism—was at the forefront of his ethos. A partial description for Rip Cord Rex (1994–2001), one of the Garbage Gods, reads: “Owner of the space station ‘mathrix,’ CEO of the ‘letter racers,’ the biggest sport ever. He is a ‘secrets’ mutant. A language miner for new letters to race and war with. . . . His secret mission is to find the fastest ‘letter engine.’ ”

Rammellzee, Garbage Gods. Installation view. Photo: Lance Brewer. Image courtesy Red Bull Arts New York. All artwork © 2018 The Rammellzee Estate.

There is a whiff of casual menace to much of Rammellzee’s work—a sly element of danger and inaccessibility. While his erstwhile “Beat Bop” collaborator Basquiat long ago entered the pantheon of ultra-expensive collector trophy art, Rammellzee will always feel like part of the underground. His work isn’t something that hangs easily above a sofa; it has a grotesqueness to it, a sense of unease. Rammellzee was a great and often baffling artist—one who resisted being easily understood. We will be decrypting his potent codes for many years to come.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist, specializing in writing on twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.