Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

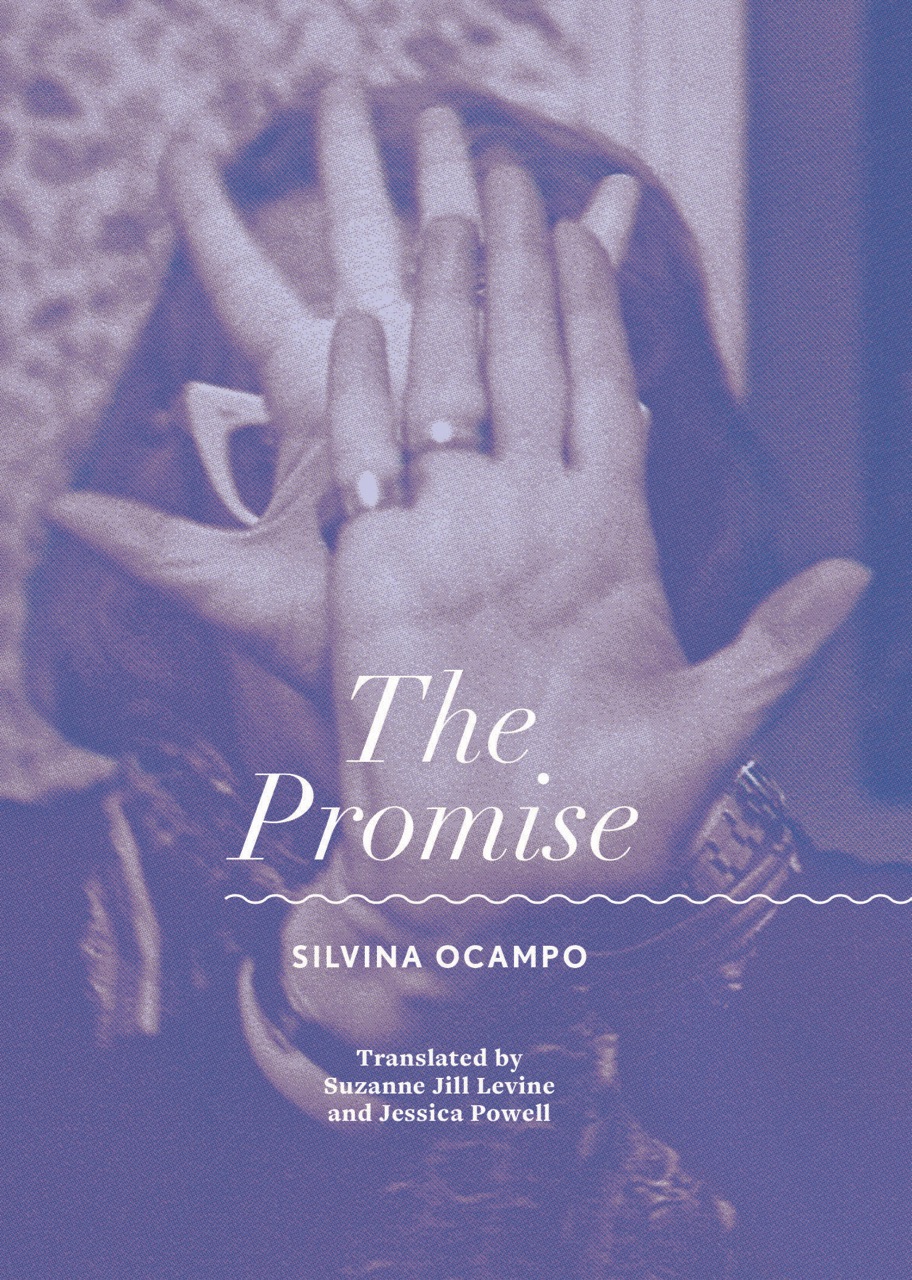

Argentine writer Silvina Ocampo’s sole novel receives its first

English translation.

The Promise, by Silvina Ocampo, translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Jessica Powell, City Lights, 103 pages, $14.95

• • •

The Argentine writer Silvina Ocampo may sound like a figure from a distant Modernist world. She was born in Buenos Aires in 1903, studied painting in Paris under Fernand Léger and Giorgio de Chirico, and in 1940 married Adolfo Bioy Casares, author of the fantastical novel The Invention of Morel. Their friend Jorge Luis Borges was best man at the wedding; he and Casares were contributors to Sur, the literary journal Silvina’s sister Victoria had founded in 1931. The fascinations of this milieu have somewhat overshadowed Ocampo’s work, though she published seven collections each of poetry and short fiction, several children’s books, and translations of Donne, Baudelaire, and Verlaine, among other poets. William Carlos Williams translated a poem of Ocampo’s as early as 1958, but a wide view of her work has emerged in English only belatedly. The Promise is her sole novel, begun in the mid-1960s and left definitively unfinished at the author’s death in 1993. It’s an extraordinary book, for which only Borges’s description of her writing will do—clairvoyant.

Ocampo’s narrative premise is elegantly unnerving. A nameless female narrator has traveled by ocean liner from Buenos Aires to visit relatives in Cape Town, there been taken ill, and while returning home fallen into the sea, unnoticed by passengers or crew. In her mind she makes a pact with Saint Rita of Cascia, patron saint of lost causes: if she survives, she will write and publish a book before her next birthday—“though I’ve always thought it useless to write a book.” This ideal, dreamed, impossible volume will be composed of the woman’s thoughts as she floats alone, alternately hoping and resigned. In other words, in a dark parody of the Künstlerroman tradition, the book will be the novel we are about to read. “In order not to sleep,” she tells us, “I imposed an order on my thoughts, a kind of mental journey or itinerary I now recommend to prisoners or patients who cannot move or to those desperate souls on the verge of suicide.”

What follows is a collage of overlapped, sometimes antagonistic, memories. She thinks about her schoolteachers, noodles, movies she’s seen, the prices of things, theater productions, the names of writers and their books, gardens, buildings, a cat, an unhappy love affair, a chair, a flower whose name she cannot recall, a perfume, a toothpaste. Is that what memory, or the life it purports to reconstruct, is made of? A catalog, an inventory, or collection of names and things and moments? Not exactly: the incantatory order of the list, intoned to keep herself awake, soon gives way to more complex portraits of people this woman has known. A decade or so into its writing, Ocampo called her novel “phantasmagorical,” and this I suppose is what she meant: these figures manifest and fade again like ghosts, and it’s quite unclear if they have ever existed.

Some of these specters are vividly drawn but only fleetingly invoked. There is Marina the fruit vendor, “blond, fair-skinned and jittery”; Mr. and Mrs. Arévalo, who run an antiques shop and have “tiny faces like rubber balls”; and Mr. Pigmy: a man whose photograph she was once shown in a magazine, who had been taken from his jungle home in the Congo, and subsequently “died of sadness.” The most insistent characters are Irene, a medical student; Irene’s obsessive daughter, Gabriela; and a handsome, disreputable young doctor named Leandro, who is Irene’s lover. Their stories are told separately, but the sections intersect and repeat each other—so much so that Ocampo’s secretary had to make a note in the manuscript to say it was all deliberate: “the memories are recurrent.” Recurrent, but altered. Leandro, for example, declares: “It would be better if humanity didn’t exist, human beings are utter crap.” And five pages later, in an alternate telling of the same exchange: “It would be better if humanity didn’t exist, to suffer so much.”

A novel about the writing of a novel, then, in which plot and character are at best ambiguous rumors. Nothing is certain about the doomed woman’s memories except that they keep coming, spooling out like the internal monologue of one of those solitary garrulous derelicts in Beckett. The narrator of The Promise hears this voice as if it is not her own: “Sometimes I was surprised by the vivid presence of what I was imagining, formulated in a single phrase.” Which sounds like a description of writing itself, the weird sense that however you labor at it, trying to put order on thought or memory or imagination, the words will seem to have come from somebody else. That is a venerable cliché, of course, but so too is a life flashing before the eyes of a drowning soul. Ocampo’s particular art is to have turned such obvious themes into a work of delirious precision.

A sort of horrified lyricism keeps returning in The Promise, as the narrator is pulled back from the sea of memory to her present in the ocean. It rains on the water, fish swim around her, she wonders what else is living in the fathoms below, waiting. Her body and personality begin to dissolve into the Atlantic. She hallucinates trees, gardens, animals, a raft laden with fruit. “These long days remind me of the city. Could the water, or coexistence with the water, be so similar to the rest of life?” We’re told that Ocampo struggled to finish her only novel because she had begun to suffer from Alzheimer’s; as her character’s past recedes and the empty ocean claims her, the author seems to be describing her own end. But if that’s the case, the lucidity with which she does it renders autofiction moot, because this long goodbye belongs to us all: “I am looking at a vanishing world, the world that abandons me, that holds me in its arms and that I cannot restrain.”

Brian Dillon’s Essayism: On Form, Feeling, and Nonfiction is published by New York Review Books. He is working on a book about sentences.